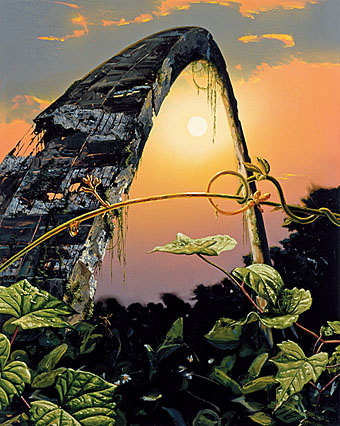

Stalker (1979).

Among the new documentary films being shown at the Sheffield (UK) Doc/Fest is Igor Mayboroda’s Rerberg and Tarkovsky: The Reverse Side Of “Stalker”. Behind the unwieldy title there lies an exploration of the troubled genesis of one of my cult artefacts, Andrei Tarkovsky‘s 1979 science fiction film, Stalker, a personal adaptation by the director of a Russian sf novel, Roadside Picnic, by Arkadi & Boris Strugatsky. Tarkovsky’s production suffered from technical calamities, illness, artistic disagreements and, worst of all, location work in a polluted area which (allegedly) caused the early deaths of a number of the people involved, including the director and leading actor, Anatoli Solonitsyn. All of which makes the completed film seem both miraculous and chilling for reasons beyond its uniquely sinister atmosphere.

When the British Film Institute launched a survey on “the film you would like to share with future generations”, behind Blade Runner in first place was a surprise second place entry: Andrei Tarkovsky’s science fiction film Stalker, in which a guide leads two clients to a site known as “the Zone”, which has the supposed potential to fulfill a person’s innermost desires. This creative documentary tells the remarkable story behind the making of Stalker, including the series of conflicts which led to crew members, most notably celebrated director of photography Georgi Rerberg, being left off the credits, leaving careers in tatters. Far from your standard making of doc, Director Igor Mayboroda has woven an engrossing “documentary cinema novel” which not only stands as a tribute to Rerberg’s career but also as a delight for cinephiles interested in how the creative process can flourish even under the most difficult and ultimately devastating of circumstances.

Stalker as it currently exists on DVD has a couple of interviews about the making of the film but nothing as substantial as Mayboroda’s documentary which sounds like essential viewing. Those in the Sheffield area can see a repeat showing on November 8.

Also at the Doc/Fest is a new film for the BBC’s long-running arts series, Arena, which will no doubt be screened on TV in due course. Eno is directed by Nicola Roberts and—needless to say—its subject is musician, producer, artist, etc, Brian Eno. Arena has always used Eno’s short piece, Another Green World, for its theme music but I believe this is the first time he’s been profiled in the series. Roberts also directed the excellent 1994 Arena doc, Philip K Dick: A Day in the Afterlife, so I’ll be looking forward to seeing this one as well.

• Danger! High-radiation arthouse! | Geoff Dyer on his own Stalker obsession.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Brian Eno: Imaginary Landscapes

• The slow death of modernism

• Thursday Afternoon by Brian Eno

• The Stalker meme