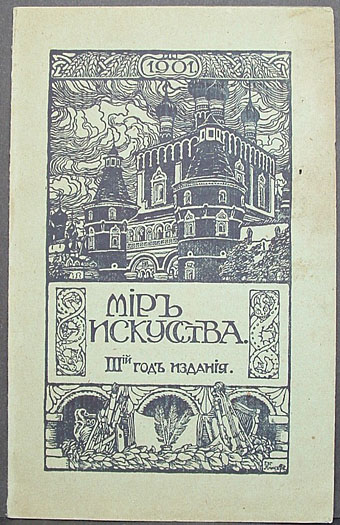

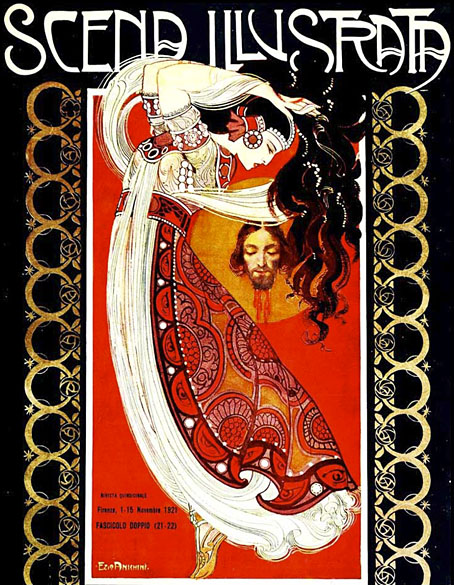

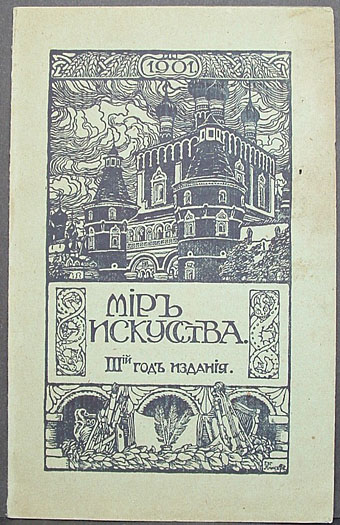

Cover by Evgeny Lanceray for Prospectus of the Magazine, 1901.

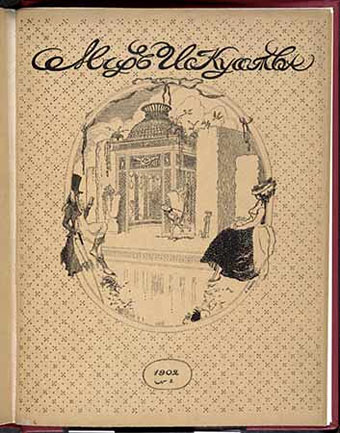

Previous posts here have concerned fin de siècle art magazines like The Savoy, Pan and Jugend; yesterday we had Sergei Diaghilev so it seems fitting to mention Diaghilev’s own magazine, Mir Iskusstva (World of Art), founded in 1899 with similar intentions to the European magazines which were highlighting developments in art beyond the academic sphere. Mir Iskusstva was also the name of the Russian art group who used the magazine as their forum, and a number of the artists involved in the movement, notably Léon Bakst, Ivan Bilibin and Nicholas Roerich, went on to work for Diaghilev at the Ballets Russes.

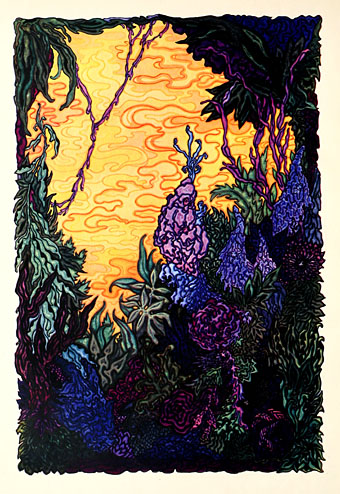

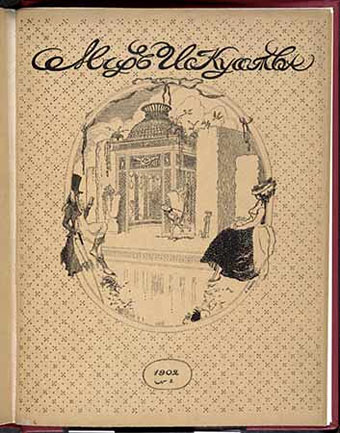

Cover by Léon Bakst for Mir iskusstva #8 (1902).

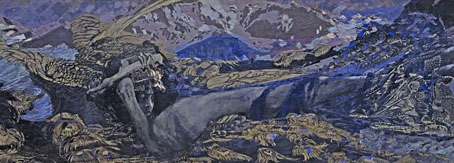

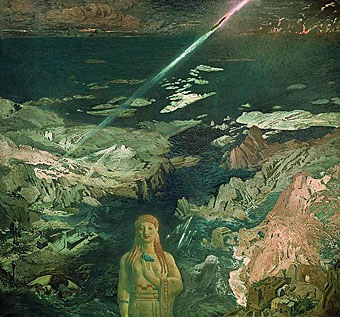

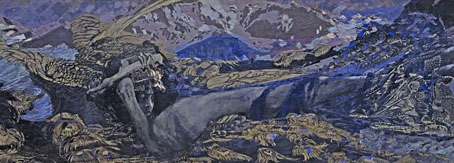

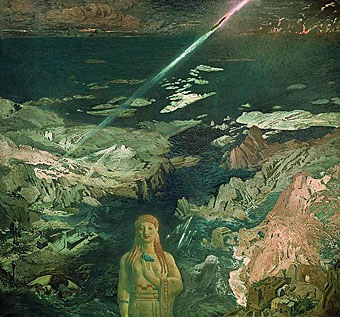

I find this later development especially fascinating since it positions the magazine as a precursor to the groundbreaking works which followed rather than being—as so many periodicals were and still are—a publication which had its moment of glory then faded from view. Of the works shown here, Vrubel’s Symbolist Demon, one of several painted by the artist, was featured in a 1903 edition of the magazine, whilst the Bakst painting, depicting the destruction of Atlantis, shows a Symbolist side to an artist who later became far better known for his Ballets Russes costume designs.

Demon (1902) by Mikhail Vrubel.

Unlike the other magazines mentioned above, I’ve yet to come across a cache of whole editions of Mir Iskusstva (and I’m still waiting for Ver Sacrum to turn up somewhere). This page has an overview of the Russian art movement and its journal, while this page has a selection of works by the artists involved. For more of Vrubel’s work, Wikimedia Commons has the best collection of the artist’s paintings and sculpture.

Terror Antiquus (1908) by Léon Bakst.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Diaghilev and the Ballets Russes

• Pamela Colman Smith’s Russian Ballet

• The art of Ivan Bilibin, 1876–1942

• Magic carpet ride

• Le Sacre du Printemps

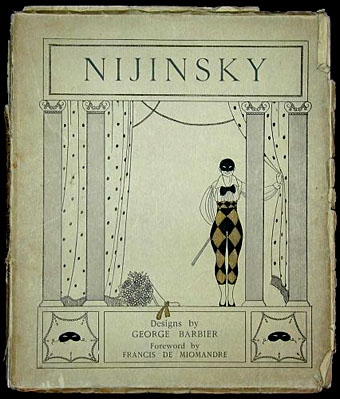

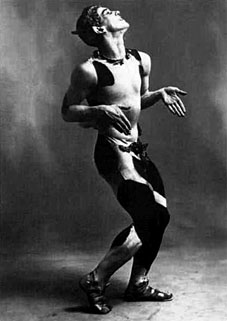

• Images of Nijinsky

I have an abiding fascination with the

I have an abiding fascination with the