Aubrey was a TV play for BBC 2’s Playhouse strand, an eighty-minute drama enacting events from the last three years of Aubrey Beardsley’s life. It was broadcast on 22nd January, 1982, and never repeated. After I digitised my own VHS copy in 2008 I wrote a somewhat taunting post about it, showing stills from the scenes that matched Beardsley’s drawings while refusing to make the video itself more widely available. I was subsequently surprised when the writer of the play, John Selwyn Gilbert, turned up in the comments to justifiably bemoan the BBC’s refusal to make so much of its vast archive publically available, an iniquity always compounded by the British public having paid for all those broadcasts in the first place.

Fast-forward seventeen years and here at last is a copy of Aubrey at YouTube, albeit in compromised form (see below). Since I wrote my original post I’ve become more acquainted with the TV productions of director Philip Hammond so it’s worth giving Hammond a little more credit for the success of the production than I did originally. Hammond’s directing career ran from the 1960s through to the 1990s, with significant contributions to Granada TV’s landmark adaptations of the Sherlock Holmes stories, and a very creditable three-part adaptation of Sheridan Le Fanu’s Uncle Silas which the BBC broadcast as The Dark Angel in 1989. Television has never encouraged the kinds of stylistic flair you find in cinema but Hammond’s later productions stand apart in their mise-en-scene and frequent use of artistic detail. Many of his later productions achieve unusual effects by shooting scenes through reflections in sheets of glass. Elsewhere you’ll often find characters framed in mirrors (as happens in the opening scene of Aubrey) or lit by saturated light from a stained-glass panel.

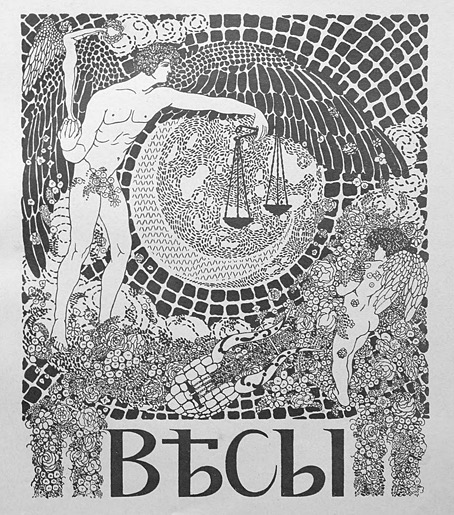

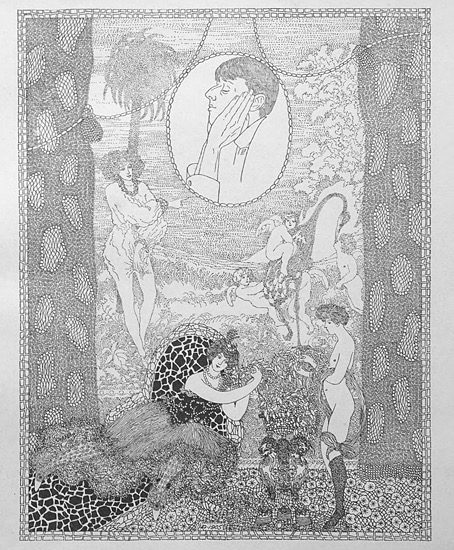

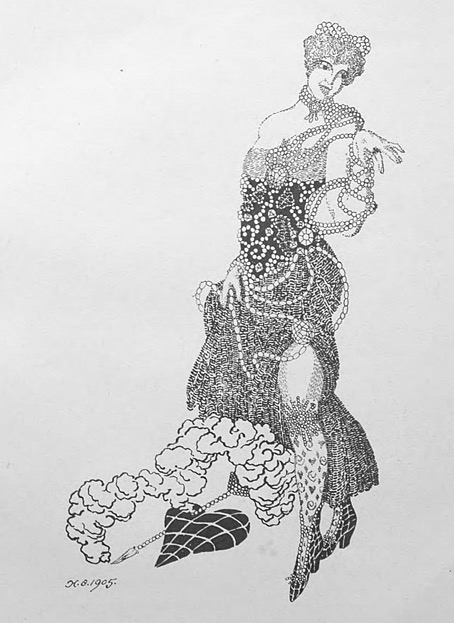

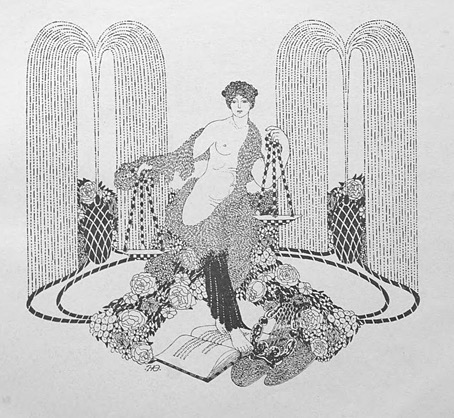

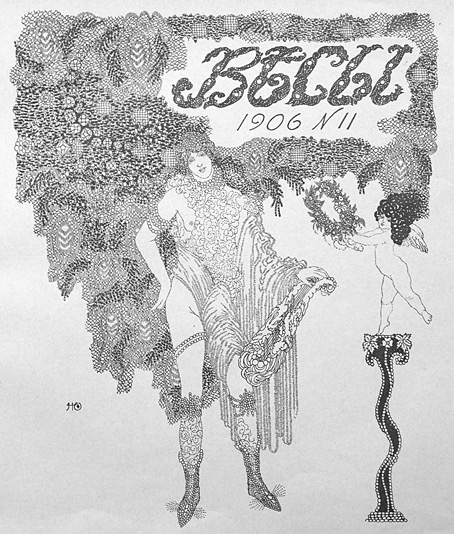

Hammond takes a different approach with Aubrey which was shot on video in studio sets. The production design is almost exclusively black and white; many of the sets and compositions frequently mimic Beardsley’s drawings, with decorative motifs framing the scenes. The general appearance is stagily artificial but the details of the script are nevertheless accurate. John Selwyn Gilbert was also the writer, producer and narrator of Beardsley and His Work, a documentary which had been broadcast on BBC 2 three days before Aubrey. Gilbert’s drama follows Beardsley from his dismissal as art editor of The Yellow Book in 1895, through the foundation of The Savoy magazine with Arthur Symons and Leonard Smithers, to his untimely demise in Menton on the French Riviera. Rula Lenska plays Aubrey’s sister, Mabel, with Sandor Elès as André Raffalovich, Simon Shepherd as John Gray, Ronald Lacey as Leonard Smithers, Christopher Strauli as Arthur Symons, Mark Tandy as WB Yeats, and Alex Norton as Max Beerbohm. John Dicks was evidently chosen for his facial resemblance to Beardsley but he’s a decade too old for the role, and looks too healthy for an artist enduring the final stages of a tubercular illness that would eventually kill him. But this is a minor complaint.

More of a problem is the way the play has been uploaded to YouTube in the wrong screen ratio. All TV broadcasts prior to the 1990s are 4:3 but this one has been horizontally compressed to something closer to a square. It is possible to rectify this if you download the video (I currently use 4K Video Downloader) then use Handbrake to write a new copy of the file with the picture size set to a 4:3 ratio. Or maybe you’d rather watch the squashed version…

And while I’m on the subject of Beardsley on screen, Chris James has made available a new copy of his short animated film, After Beardsley, which is now complete, and not chopped into three parts as it was before.

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The Aubrey Beardsley archive