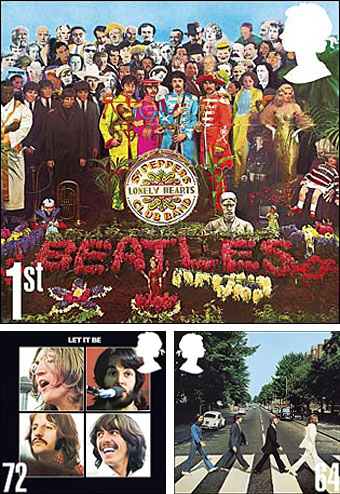

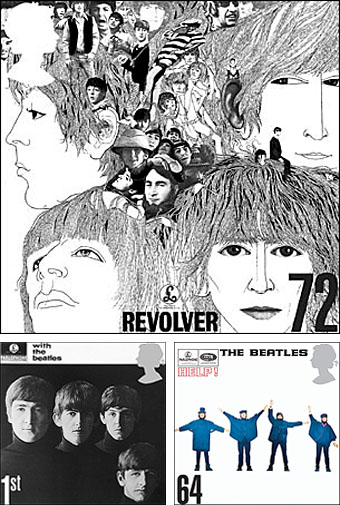

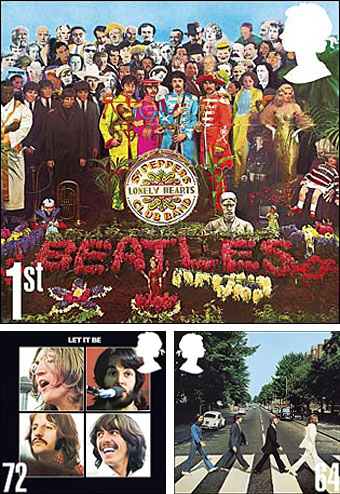

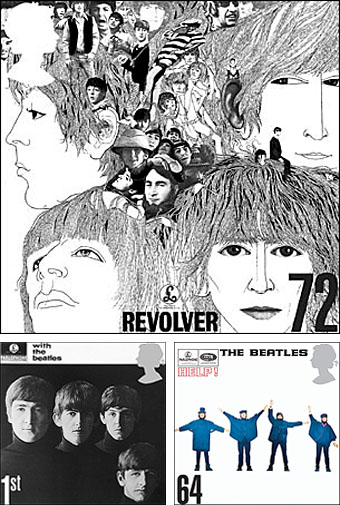

The Beatles get the Royal Mail treatment in a new series of UK stamps next month.

A journal by artist and designer John Coulthart.

The Beatles get the Royal Mail treatment in a new series of UK stamps next month.

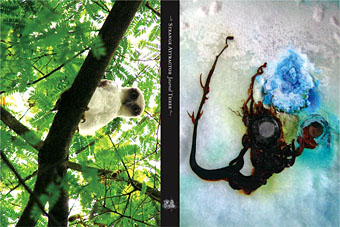

Yes, it’s that magazine again, the perfect thing to feed your head for the new year.

Mark P and SAJ are profiled in the latest Wire.

Ken Hollings rides the world’s subcultural currents mapped by London’s Strange Attractor.

The Wire #275, January 2007

Strange Attractor is well named. There’s really no escaping it. Starting out as a series of live events, it has slowly transmuted into an annual publication, set up an online clearing house for the weird and the wonderful and recently made its first move towards establishing itself as a publishing house. “Strange Attractor celebrates unpopular culture,” runs its mission statement. “We declare war on mediocrity and a pox on the foot soldiers of stupidity. Join us.” Who could possibly resist such a challenge? Sooner or later you have to get involved. (In the interests of full transparency: the writer of this article has taken part in a number of Strange Attractor evenings and is a regular contributor to Strange Attractor Journal.)

With orders for the Strange Attractor publications coming in from all over the world, and mainstream media like The Independent On Sunday praising it for producing “one of the most weirdly beautiful, beautifully weird magazines of the past hundred-odd years” a bigger problem presents itself. How do you celebrate unpopular culture without losing its unpopularity?

“There’s certainly no business plan,” admits Strange Attractor Journal‘s publisher and chief editor, Mark Pilkington. “We’re really making it all up as we go along. I hope that Strange Attractor‘s approach to culture is simultaneously that of the archaeologist, the ethnographer, the anthropologist, the occultist, the showman and the curator.”

It’s a heady mix. The first two issues, both book-sized anthologies running to more than 200 and 400 pages apiece, have presented material ranged across such elusive topics as mind control experiments, mould art, hair sculpture, cargo cults, neglected gods and forgotten waxworks. Such a list limits more than it clarifies, however. Strange Attractor Journal is concerned less with the unexplained than with the unexpected. You never know what it will cover next.

“I think Strange Attractor is refreshing to people in that it manages to straddle several cultural channels while still following its own agenda,” Pilkington admits, “and it’s one not driven by the same obvious memes. But at the same time it’s important that it doesn’t become obscurantist for its own sake—some things are lost for a reason, others will only resurface when the time is right.”

Strange Attractor‘s wayward eclecticism dates back to a series of monthly events begun in the summer of 2001 by Pilkington in collaboration with artist John Lundberg and continuing over the next two years. Staged at London’s Horse Hospital venue, they gave an early indication of the loose network of experimental enterprises that was starting to come into existence, linking outsider artists with cultural anthropologists, textual hackers and practising occultists.

“We’d mix talks, films, music, presentations, each night being themed around a different topic,” Pilkington recalls. “I rather pretentiously called them ‘information happenings’. Subjects ranged from conspiracy theory to theremins, Esperanto to magick, hoaxes, illusions and psychic deceptions: basically anything that interested us and could draw people that we liked or wanted to meet into one place.” Highlights included a live and bloody demonstration of psychic surgery, sci-fi movie themes played on vintage electronic instruments and a live Lovecraft-influenced Chaos Magick ritual with a soundtrack performed “by a band who couldn’t see what was going on.”

After Lundberg enrolled at the National Film and Television School, Pilkington went solo but eventually grew tired of doing regular live events, deciding instead to do something that would last longer: hence the Journal.

The notion of outliving the moment, of being around for more than just a quick cultural fix, is very much a part of SAJ‘s overall look and feel. The first thing you notice is that the front and back cover of each issue is devoid of text or title, which only appears on the book’s spine. If you want to know who the contributors are, you’ll have to look inside.

“For me, it was about giving as much space as possible to striking images and therefore making them stand out on the bookshelf,” Pilkington explains. “I imagined people being aware that something was wrong with the cover but perhaps not being able to put their finger on it.”

The absence of cover copy also binds together the Journal‘s various contributors in the anonymity of a collective endeavour. “We’re lucky enough to live in an age where we can clearly trace the influences of the past on our present,” Pilkington continues, “and it’s not always today’s most celebrated ideas, musicians and writers who will be remembered. This notion of timelessness is very important to what SAJ is and does. I’d like the books to be as irrelevant to a reader 100 years in the future as it would be to someone 100 years in the past. It’s a re-manipulation of the notion of built-in obsolescence.”

The Journal‘s pages teem with old woodcuts, antiquated typefaces and intricate layouts, giving the impression of having been produced in some parallel past: one that runs counter to established tenets of historical development. Having previously worked as a journalist for periodicals as varied as Fortean Times, Bizarre and The Guardian, Mark Pilkington remains keenly aware of what’s going on around him.

“There’s a particularly vibrant, very loose cultural network in London at the moment,” he remarks, “one that incorporates music and sound, ideas and information, visual arts and almost anything else you’d care to imagine. It’s inevitable that these people, places and events all bounce off and influence each other in a kind of subcultural Brownian motion.”

As well as working closely with designer Alison Hutchinson, readying volume three for publication, Pilkington has also been getting Strange Attractor Press up and running. Its first book to date, The Field Guide: The Art, History And Philosophy Of Crop Circle Making by Rob Irving and John Lundberg, is a particularly cerebral blend of art theory, paranormal phenomena, hoaxes and speculations, ruggedly bound and designed to fit snugly inside your knapsack while out exploring the British countryside. Conventional wisdom says it shouldn’t work, but Strange Attractor‘s own particular blend of parlour magic proves that it does.

“I sometimes see myself as a medium,” Mark reveals, “a channel for all the material that has formed Strange Attractor. I’ve been incredibly lucky with the amazing contributions the Journal has attracted so far.”

There’s no escaping it. Strange Attractor really is well named.

Strange Attractor Journal Three, and The Field Guide: The Art, History And Philosophy Of Crop Circle Making by Rob Irving & John Lundberg, are available now.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Strange Attractor Journal Three

• How to make crop circles

“A trap for dere Santa”. From How to be Topp by

Geoffrey Willans and Ronald Searle (1954).

That time of year again. Here at { feuilleton } we prefer to acknowledge the solstice-based traditions that pre-date the usurping rituals of Middle Eastern sky gods. The old pagan business of lighting fires and creating artificial light and warmth still makes sense when you’re in the depths of another dreary English winter, with seemingly permanent grey skies and a smear of daylight that vanishes at half past three in the afternoon. Christmas used to agitate me too much and too often until the year the TV finally gave up the ghost. I realised a lot of the prior aggravation had been caused by the deluge of trivia that popular media creates at the end of the year; keep away from TV, avoid the crowds and the collective hysteria become a lot more manageable.

This page will be quiet while I visit the family for a few days but the archive feature will be active should you be seized by a sudden desire to read my words or look at some pictures. If you’re sat in front of a monitor over the coming week—and for some this may be a necessary escape—I’d suggest looking over some of the mp3 blogs that have been coming online in the past year. These are from people (usually anonymous for good reason) posting whole albums for download, many of which still haven’t made it onto CD. Hard to say how long this phenomenon will be allowed to continue in its current form—a lot of these places are using Blogger, so may be shut down by Google eventually—but for now its an encouraging trend. A by-no-means-definitive list follows below. These are only the ones I’ve run across recently, liked and bookmarked; if you know of any other good ones, feel free to leave a tip in the comments.

Fauni Gena Music Webbernet. Mainly ambient or quiet electronic releases.

À bientôt j’espère. Er…hard to describe, you’ll just have to go and look.

Lost-In-Tyme. Obscure psychedelia for the most part.

Swen’s blog – Artists mentioned in The Wire. What it says on the tin. Very useful if you’re a Wire reader.

Improvisie. Improvised music with an emphasis on the jazz spectrum. Not much there yet but may be worth watching and worth a visit solely for the insane Paul Bley synth album. (Thanks to Gav for the tip!)

Grown So Ugly. “A home for musical gems from the past fifty years, decidedly biased in favor of acoustic instrumentation. From the easily accessible to the challenging listen, quality is the sole requirement for our sharity. We encourage community participation.” (Thanks to Jay for pointing me to this one.)

Krautrockteam. Best of the lot where my tastes are concerned. More obscure (that word again…) German music than you can shake an Archangel’s Thunderbird at.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• The music of The Wicker Man

The Guardian of Paradise by Franz Stuck (1889).

We’ll let Coil have the final word on the angel theme, the post title being taken from their Cathedral In Flames. Those words recognise—as does the painting above—that the Christian concept of Heaven is of a gated community guarded by warriors to keep the undesirable at bay.

Symbolist painter Franz Stuck was (as far as we know) robustly heterosexual but his angel isn’t far removed from the work of contemporary photographers like Anthony Gayton who specialise in teasing out the erotic undercurrents in this kind of imagery. Which brings us full circle, seeing as we started with Caravaggio and his distinct brand of religious subversion. The irony is that some of the more vocal elements of Christianity can’t help subverting themselves or their own messages, as John Patterson notes in his Guardian piece today, alluding not only to the Ted Haggard debacle but also to Haggard’s favourite artist, Thomas Blackshear, both of whom were discussed here in November. Patterson writes that the recent brand of bigoted fervour that’s swept America seems to have abated, or at least retreated, after threatening to become a mainstream force. Europe often seems a haven of healthy heathen sanity by comparison, a part of the undesirable world being kept outside the American Paradise. St. Peter now demands retinal scans, fingerprints and a biometric passport. Continual rumbles from Pope Maledict and his closeted cardinals are an increasing irrelevance, the background static of a dying regime. Paradise may be guarded by attractive angels but we can only look and never touch. As Patterson says, the devil has all the best tunes. And the best books and movies and games. And sex and fun. I know which side of the fence I’d rather be on.

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The gay artists archive

• The men with swords archive

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Gay for God