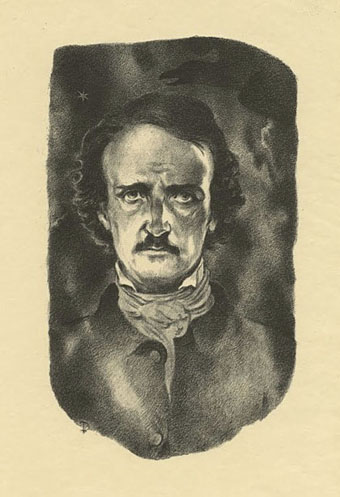

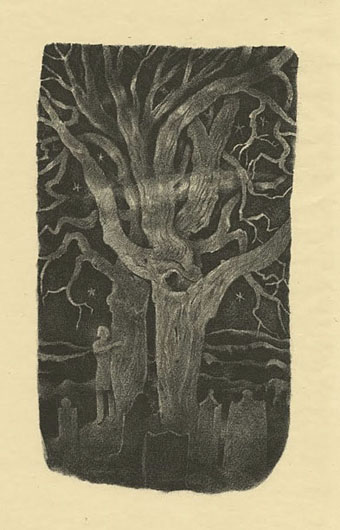

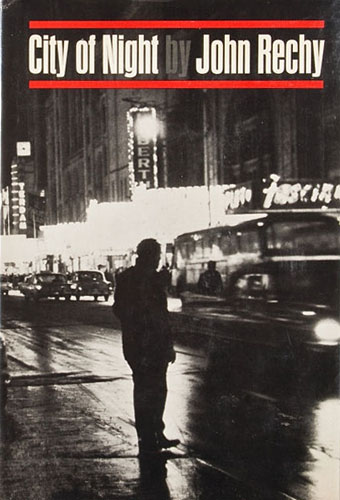

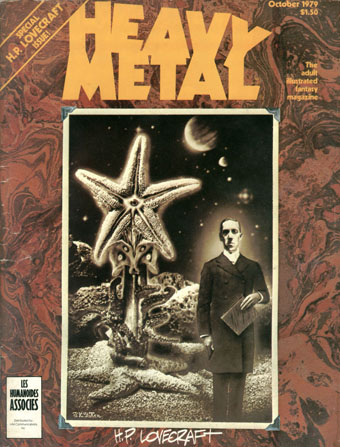

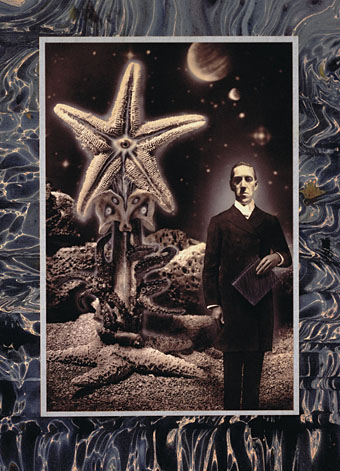

American artist JK Potter is another photo-montagist whose work since the 1970s has been very popular as illustration for books of horror, fantasy and science fiction. Potter’s portrait of HP Lovecraft on the October 1979 issue of Heavy Metal was my first introduction to his work. The original version of that picture can be seen below. Despite Potter’s flair for horror imagery there’s fewer Lovecraft illustrations than you might expect, certainly fewer than I used to hope there might be, although tentacles—real ones—do feature in a number of his other pictures.

While we’re on the subject, HPL continues to dog my footsteps. I recently autographed an enormous block of contributor signing sheets for a new doorstop anthology from Centipede Press. A Mountain Walked is a 636-page collection edited by Lovecraft scholar ST Joshi which will be published in March, 2014. Be warned that like many other Centipede volumes it won’t be cheap! Meanwhile I’m currently working on a new series of illustrations for a completely different anthology of Lovecraftian fiction. That will also be out early next year. It’s going to be a good one but I’ll say more about it at a later date.

Tales of the Cthulhu Mythos (1990).

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The Lovecraft archive