We tend to think of cinema as a modern medium, quintessentially 20th century, but the modern medium was born in the 19th century, and the heyday of the Silent Age (the 1920s) was closer to the Decadence of the fin de siècle (mid-1880s to the late-1890s) than we are now to the 1970s. This is one reason why so much silent cinema seems infected with a Decadent or Symbolist spirit: that period wasn’t so remote and many of its more notorious products cast a long shadow. Even an early science fiction film like Fritz Lang’s Metropolis has scenes redolent of late Victorian fever dreams: the vision of Moloch, Maria’s parable of the tower of Babel, the coming to life of statues of the Seven Deadly Sins, and—most notably—the vision of the Evil Maria as the Whore of Babylon. Woman as vamp or femme fatale was an idea that gripped the Decadent imagination, and it found a living expression in the vamps of the silent era, beautiful women with exotic names such as Pola Negri, Musidora (Irma Vep in Feuillade’s Les Vampires) and the woman the studios and press named simply “the Vamp”, Theda Bara (real name Theodosia Burr Goodman).

We tend to think of cinema as a modern medium, quintessentially 20th century, but the modern medium was born in the 19th century, and the heyday of the Silent Age (the 1920s) was closer to the Decadence of the fin de siècle (mid-1880s to the late-1890s) than we are now to the 1970s. This is one reason why so much silent cinema seems infected with a Decadent or Symbolist spirit: that period wasn’t so remote and many of its more notorious products cast a long shadow. Even an early science fiction film like Fritz Lang’s Metropolis has scenes redolent of late Victorian fever dreams: the vision of Moloch, Maria’s parable of the tower of Babel, the coming to life of statues of the Seven Deadly Sins, and—most notably—the vision of the Evil Maria as the Whore of Babylon. Woman as vamp or femme fatale was an idea that gripped the Decadent imagination, and it found a living expression in the vamps of the silent era, beautiful women with exotic names such as Pola Negri, Musidora (Irma Vep in Feuillade’s Les Vampires) and the woman the studios and press named simply “the Vamp”, Theda Bara (real name Theodosia Burr Goodman).

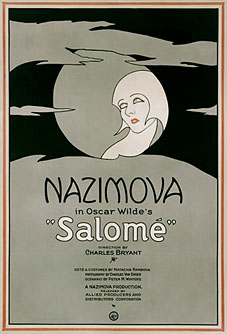

Alla Nazimova was another of these exotic creatures, and rather more exotic than most since she was at least a genuine Russian, even if she also had to amend her given name (Mariam Edez Adelaida Leventon) to exaggerate the effect. Like an opera diva or a great ballerina she dropped her forename as her career progressed, and is billed as Nazimova only in her 1923 screen adaptation of Oscar Wilde’s play, Salomé. Nazimova inaugurated the project, produced it and even part-financed it since the studios, increasingly worried by pressure from moral campaigners, regarded it as a dangerously decadent work. Nazimova had a rather colourful off-screen life and the stories of orgiastic revels at her mansion, the Garden of Allah, probably didn’t help matters.

Salomé lobby card (1923).

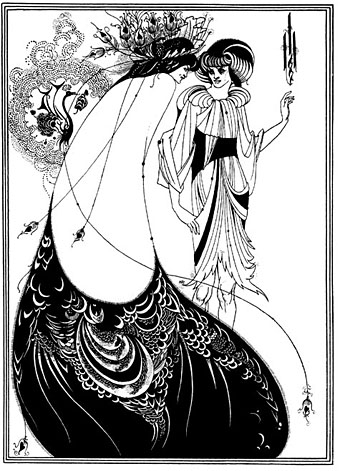

Salomé: The Peacock Skirt by Aubrey Beardsley (1893).

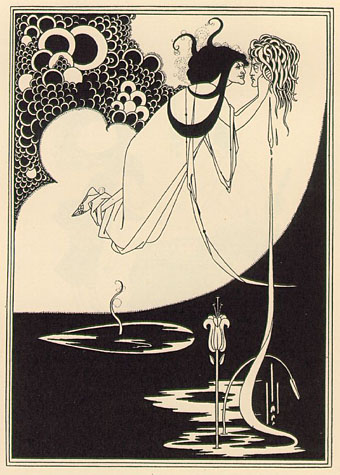

It may seem bizarre to make a silent film of a stage play but silent adaptations of Shakespeare had been around since film’s earliest days. The task of adapting Wilde was given to Natacha Rambova, wife of Rudolph Valentino. If you’re going to cut down the available dialogue, however, it helps if the audience is familiar with the story. Nazimova’s audience in 1923 would have known of Salomé from their Bibles but Wilde’s play has rarely been considered a stage masterwork and remains largely unknown even today. The film’s intertitles were deemed too wordy and the production flopped as a result. This is a shame since the film is a curiosity, not least for the decision to base the production design on the Aubrey Beardsley illustrations that have accompanied (overshadowed, even) the printed edition of the play since its first publication.

Salomé: The Climax by Aubrey Beardsley (1893).

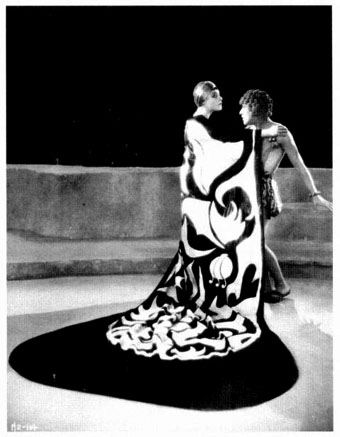

The film remains intriguing also for its distinctly gay aura. Nazimova was a lesbian and, in one of those rumours that persists around certain productions, was said to have demanded that most, if not all, the cast be gay or bisexual. The director certainly was. Charles Bryant (also an actor) lived with Nazimova in what was known at the time as a “lavender marriage”, a partnership between a gay man and a lesbian that enabled both to masquerade in a manner acceptable to contemporary mores. I haven’t read Gavin Lambert’s biography of Nazimova so details about the rest of the cast are sketchy but we know there was at least one other gay actor involved. Arthur Jasmine who played the page of Herodias was known in later life as Sampson (also Samson) de Brier and his house and person feature prominently in Kenneth Anger’s Inauguration of the Pleasure Dome (1954).

Nazimova and Arthur Jasmine in a shot modelled on Beardsley’s Peacock Skirt.

Salomé is available in the US on DVD accompanied by another curious Biblical work with prurient interest, Lot in Sodom (1933).

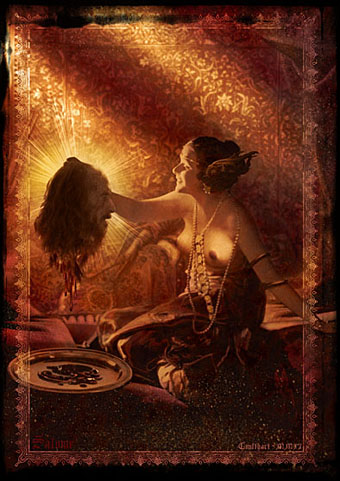

On a final note, the associations between Salomé and silent cinema carry over to my own Salomé picture from 2002. This was a Photoshop collage which began life as a rather chaste still of silent star Norma Talmadge. I gave Norma a pair of bare breasts, a beaded necklace, bangles and a severed head to hold. I hope she forgives me.

Salomé by Coulthart (2002).

• Salomé movie photo gallery

• A review from Motion Picture magazine, October 1922

• The complete text of Wilde’s play in French (as originally written) and English

• A complete set of Beardsley’s Salomé illustrations

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The Aubrey Beardsley archive

• The Salomé archive

Nice picture, John.

Thanks. :)

I’ve been wanting to buy this flick for a while. I’m just going to have to get it now. There’s no way it isn’t at least entertaining, if not fucking transfixing.

Nice info, thx.

smashing pumpkins did a video that completeloy rips this off, I forget what the song title is but its a lovely vid….

I love this! On my blog I ma serializing my novella Salome: the Seventh Queen. It takes Salome on a tour up into the wilds of Russia where she dances on ice to her death. The seventh Queen is Herodias, Salome’s mother and Queen of the Witches. Have a link if you like and a look too! Thank you — I’m taking your Beardsley as an illustration…

another fascinating one…your photo is fantastic, she looks so good, i’m sure she’ll forgive you.

i am also floored by that amazing dress, what a great photo they made with that!

I’ve been redirected to this post having seen ‘Salome’ projected with a live score some few weeks ago at the South Bank.

Nazimova was also Aunt to RKO’s Val Lewton and a major influence on his life they say – see all the coded

lesbian references in ‘Cat People’ for instance. Lewton spent much his childhood with his mother & sister at Nazimova’s and indeed, it was Nazimova’s suggestion for the name change to ‘Lewton’.