Kull of Atlantis—The Mirrors of Tuzun Thune by Ned Dameron for Kull (1985) by Robert E. Howard. Via.

• Jeremy Allen reviews the latest reissue of The New Worlds Fair by Michael Moorcock and The Deep Fix, describing the album as “a fascinating and quixotic document from the time it was made, deserving to be taken seriously in its own right”.

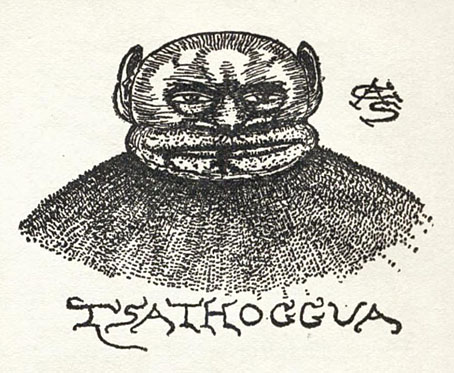

• Among the new titles at Standard Ebooks, the home of free, high-quality, public-domain texts: Short Fiction, a small collection of early stories by Clark Ashton Smith.

• New music: Geometry of Murder: Extra Capsular Extraction Inversions by Earth x Black Noi$e; Live At Nonseq by WNDFRM.

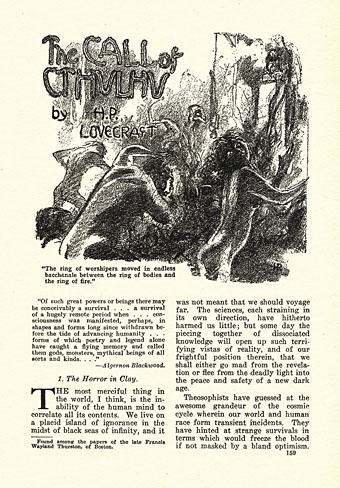

The book is not just loaded with words or tongues. Its also loaded with genres, or more accurately, different modes of literature. And one of the modes I particularly enjoyed this time around is, appropriately, the Weird. In ways long noted on forlorn and unspeakable subreddits, there is a decidedly Lovecraftian dimension to Melville’s Whale, which the Master of Providence did read and enjoy months before writing his game-changing “Call of Cthulhu.” We begin the novel with a sick soul, who may or may not be named after an Old Testament outcast, wandering through a macabre and fetid New England whale-town, following grim portents that lead him on towards a cursed ship doomed to confront a monster who sleeps or at least feeds, and presumably dreams, at the bottom of the sea. And that’s just the first couple of chapters.

Erik Davis on the pleasures of re-reading Moby-Dick, in a piece which makes me want to read the novel again

• At the BFI: Phil Hoad on David Lynch’s efforts to keep making films in an industry resistant to his kind of art.

• Exploration Log 12: Adam Rowe on the best retro science fiction art collections.

• At Public Domain Review: The Nine Birds of Jacques de Fornazeris (1594).

• Winners and finalists for the 2025 Ocean Art Contest.

• Mix of the week: A mix for The Wire by Hilary Woods.

• The Whale (1977) by Electric Light Orchestra | Don’t Kill The Whale (1978) by Yes | School For Whales (1980) by Marc Barreca