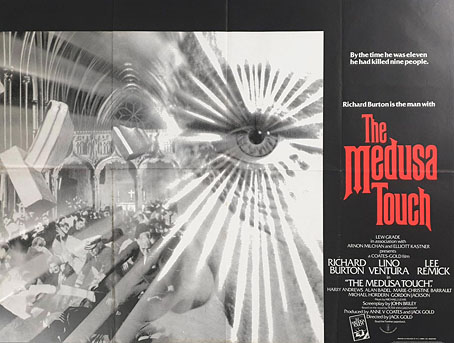

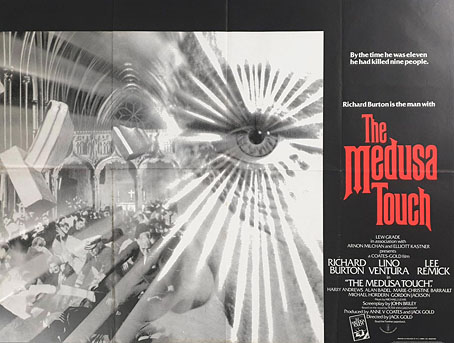

Continuing an occasional series about artworks in feature films. The Medusa Touch (1978) is the kind of film I usually dislike: a supernatural horror story with a preposterous premise—a man who causes disasters to occur with the power of his mind—which is also an ITC production directed by Jack Gold with a TV-friendly gloss, all overlit interiors and zoom-happy camera work. Richard Burton plays the man with a name you only find in horror novels, “John Morlar”, whose telekinetic gift is also a curse, the Medusa touch of the title, although his affliction is never quite described as such. It’s Burton who makes this one worth watching, he burns with a misanthropic intensity in every scene he appears in, delivering his lines with a conviction that suggests he identified rather too much with Morlar and his hatred for the world. The film unfolds as a police procedural, opening with the attempted murder of Morlar by an unknown assailant, then following the investigation that reveals the victim’s history. The police business is the weakest part of the film; being a British/French co-production means that the man leading the investigation, Inspector Brunel, is a Frenchman working in London as part of an exchange programme. Brunel’s dull character is further diminished by having him played by Lino Ventura with a dubbed voice, but it’s the inspector’s quest for clues to Morlar’s past that bring us eventually to the art.

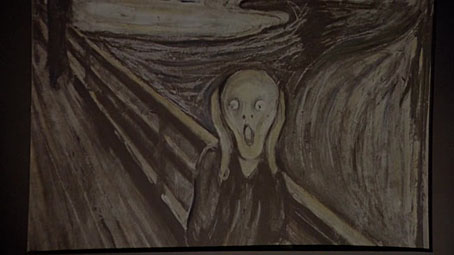

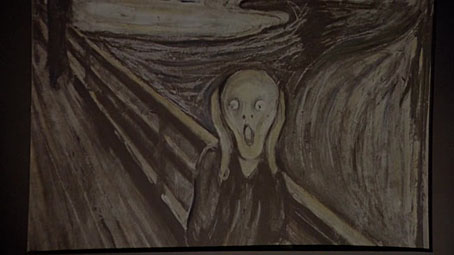

The first artwork, however, appears before all of this. The film opens in the street outside Morlar’s London home then cuts to the inside of his flat with this close view of a print of Edvard Munch’s The Scream. Munch’s most famous painting wasn’t quite the visual cliché in 1978 that it is today. Morlar’s history is recounted in a series of flashbacks which reveal him to have been a barrister whose distaste for the legal profession leads to his becoming a novelist with characters used as mouthpieces for his misanthropy. The art in his mansion flat is scrutinised by Brunel without being subjected to any discussion, leaving us to decide whether these works are the kinds of things that Morlar actually liked or exterior emblems related to his condition.

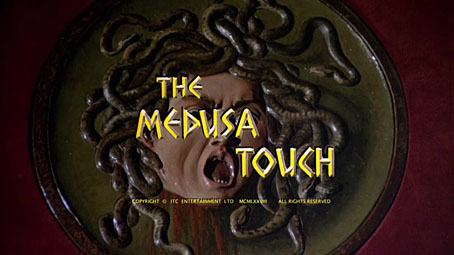

A relief based on Caravaggio’s Medusa (c.1597).

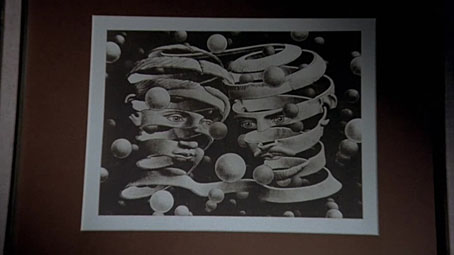

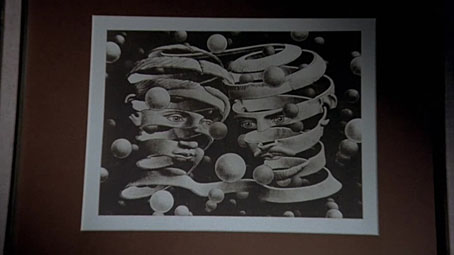

The head of Medusa pinned on Morlar’s wall suggests the latter, although the only introspective comments from Morlar come in the scenes with him and his psychiatrist, Dr Zonfeld (Lee Remick), which are mostly discussions of his calamity-filled life. Morlar and Zonfeld’s combative relationship may explain the next artwork which catches Brunel’s eye, a print of Bond of Union (1956) by MC Escher.

The choice is an unusual one when the print was made to celebrate Escher’s marriage which was relatively happy, unlike Morlar’s disintegrated union which ends with him willing his wife to death in a car crash. Escher was very trendy in the 1970s, collections of his work were being published for the first time and his prints were everywhere. A better match for a story of this type might have been Eye (1946), an image with greater symbolic resonance that would also complement all the moments when Jack Gold’s camera zooms into Morlar’s basilisk glare.

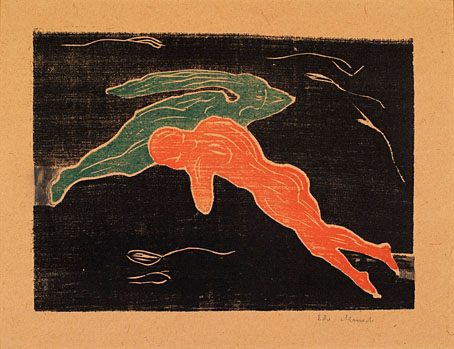

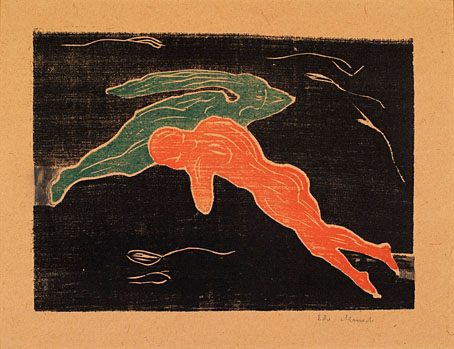

Encounter in Space (1899) by Edvard Munch.

After looking at the Escher, Brunel leafs through Morlar’s print collection, pulling out another Munch, and a very strange choice it is. This is an odd scene: the prints are all badly lit and none of them have much overt reference to either Morlar’s character or the story as a whole.

Continue reading “Art on film: The Medusa Touch”