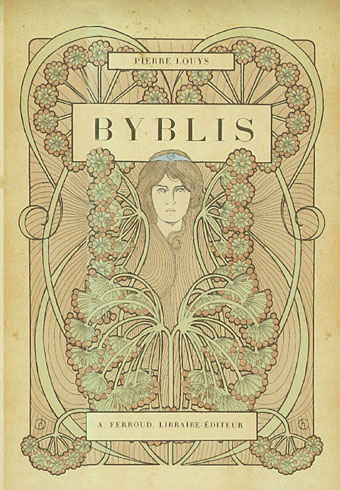

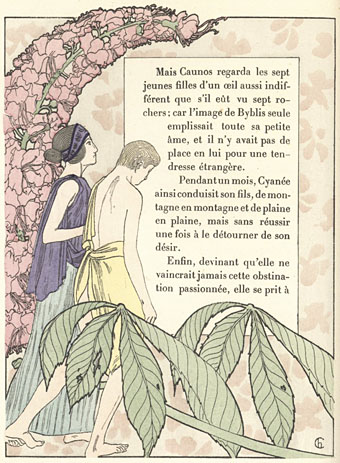

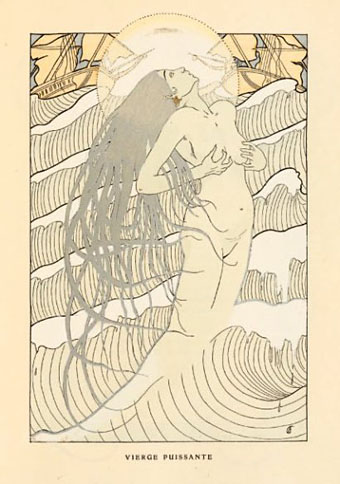

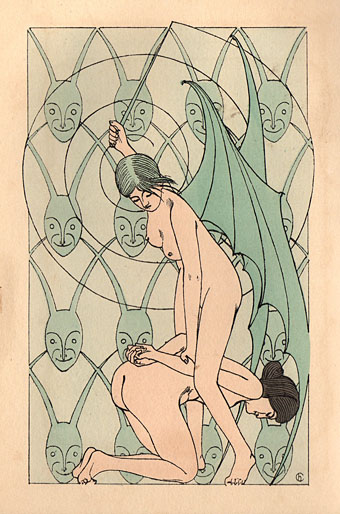

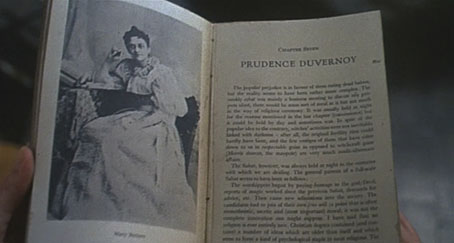

Illustration from The House of Pomegranates (1914) by Jessie M. King.

Continuing an occasional series. Recent Wildean links.

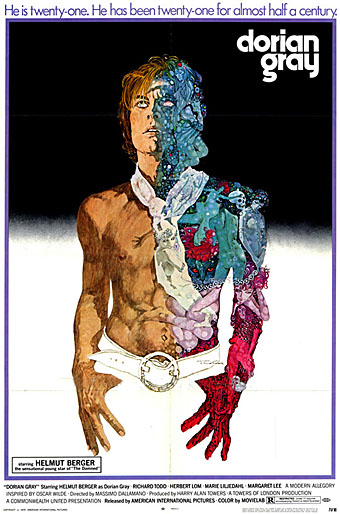

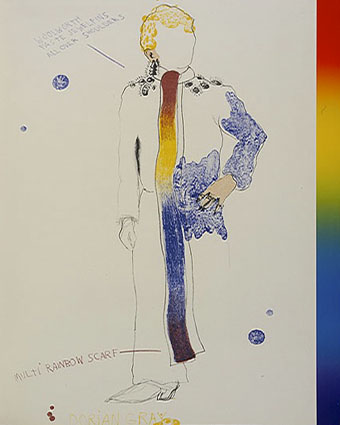

• It’s a measure of a writer’s success if the characters or stories they create resonate sufficiently with future generations to be subject to new interpretations. Among Oscar Wilde’s contemporaries this has happened to Arthur Conan Doyle and Bram Stoker, both of whom Wilde knew. Increasingly it’s been happening to Wilde’s own fiction, especially in the case of Dorian Gray whose tragedy assumes the status of a modern myth. At Cannes this year, Clio Barnard premiered a contemporary retelling of Wilde’s The Selfish Giant. Bleeding Cool has some clips. The social realism is a long way from Wilde’s tale but that shows how flexible these fables can be.

• Jessie M. King’s illustrations for Wilde’s The House of Pomegranates have appeared here before but the copies posted at The Golden Age are the usual quality scans.

• Rick Gekoski: “Visiting the US, I am reminded of Oscar Wilde’s tour there in 1881, which allowed him to become an orator and a celebrity.”

• Paper Dolls by David Claudon based on the characters from The Importance of Being Earnest. (Thanks to Gabe for the tip.)

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The Oscar Wilde archive