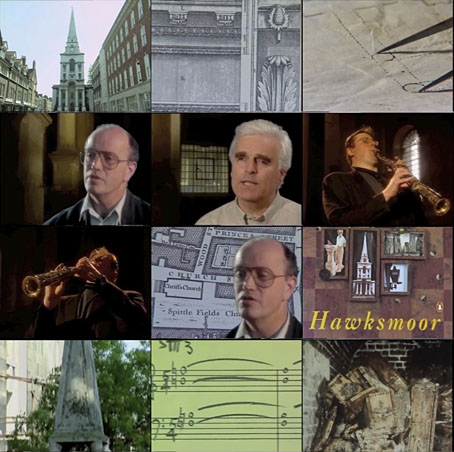

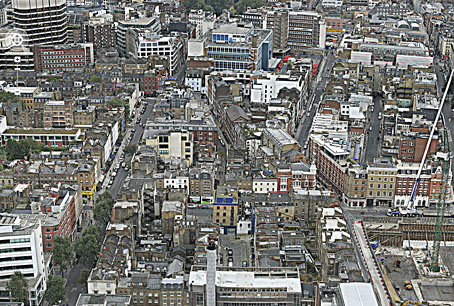

Christ Church, Spitalfields, London, in 2001. A photo I took with a disposable film camera.

And so let us beginne; and, as the Fabrick takes its Shape in front of you, alwaies keep the Structure intirely in Mind as you inscribe it. First, you must measure out or cast the Area in as exact a Manner as can be, and then you must draw the Plot and make the Scale. I have imparted to you the Principles of Terrour and Magnificence, for these you must represent in the due placing of Parts and Ornaments as well as in the Proportion of the several Orders: you see, Walter, how I take my Pen?

Hawksmoor (1985) by Peter Ackroyd

*

Bentley had laid down tracks for a shot that would feature the saxophonist and composer John Harle tooting away at his Terror and Magnificence in the setting of Hawksmoor’s church, which was now established, post-Ackroyd, as a cathedral of baroque speculation. Harle, in the notes published with the CD, writes that “darkness beneath the architecture and the very fabric of the stones pushed the idea towards a text.” The language here harks back to Ackroyd, towards privileged notions of place. The church was, in its proportions, a score to be unravelled; an overweening Pythagorean geometry to be tapped and sounded.

Iain Sinclair in Rodinsky’s Room (1999) by Rachel Lichtenstein & Iain Sinclair

Iain Sinclair first drew the world’s attention (or the minuscule portion of the world that was reading his books) to the strange character of Hawksmoor’s London churches in 1975 with Lud Heat, a book-length poem. Peter Ackroyd a decade later turned Sinclair’s esoteric excavation into a bestselling architectural murder mystery with his novel Hawksmoor, since when Sinclair’s psychogeography (if that term still has any valid currency) has found its way into From Hell by Alan Moore & Eddie Campbell, where Christ Church dominates the proceedings, and a musical work, Terror and Magnificence, by composer John Harle which takes its title from Ackroyd’s novel.

The short BBC film to which Sinclair refers can be seen on Harle’s YouTube channel. In addition to running through the Hawksmoor mythology we receive some glimpses of David Rodinsky’s abandoned room in the Princelet Street synagogue, a location (and a life) explored in detail in Sinclair’s book with artist Rachel Lichtenstein.

Bob Bentley’s film of Harle, Sinclair and Keith Critchlow was broadcast in 1995. In the same year Harle was commissioned by the BBC Proms to write an opera. The resulting work, Angel Magick, with libretto by David Pountney, advertises itself as “the first Dr Dee Opera”, a subject equally of interest to both Sinclair and Alan Moore, who in Sinclair’s Liquid City (1999) take a walk to John Dee’s home at Mortlake. (“We were a thrift-shop Dee and Kelley cupping our ears for whispers from tired stone.”) In that piece Sinclair mentions having been in on the early discussions for the opera but doesn’t go into any detail. I haven’t heard Angel Magick but you can hear a complete performance of Terror and Magnificence by the John Harle Band, the Balanescu Quartet, and the London Voices, here.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Mister Jarman, Mister Moore and Doctor Dee

• Compass Road by Iain Sinclair