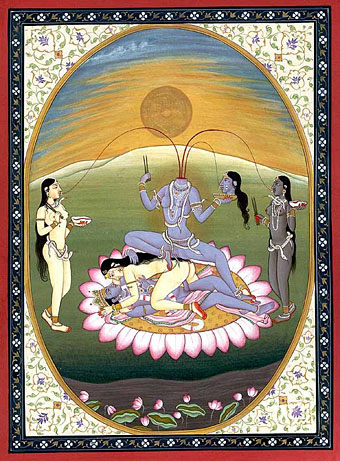

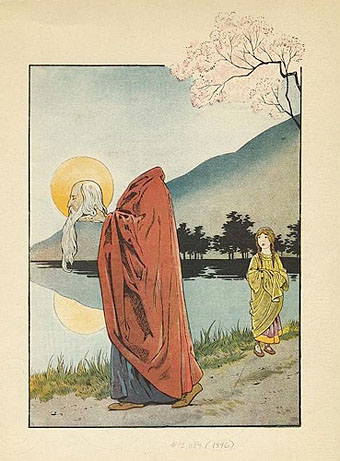

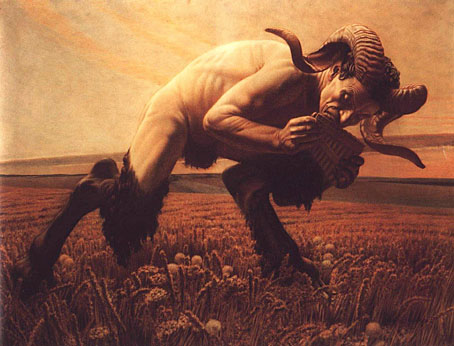

Le Faune (1923).

Yesterday’s Pan prompted me to repost Carlos Schwabe’s wonderful painting of a faun, one of my favourite faun/satyr depictions, and easily one of the best in the entire Symbolist corpus. Other satyr aficionados of the period such as Arnold Böcklin and Franz Stuck had an unfortunate knack for making their goat gods look rather foolish.

Schwabe was a German artist, and one of the more mystical of the Symbolists, with a fondness for winged figures and a preoccupation with death. The mystical end of the Symbolist spectrum is the one I enjoy the most so I often point to Schwabe or Jean Delville as exemplars of this type of art. Both Schwabe and Delville were connected briefly by Joséphin Péladan’s very mystical Salon de la Rose + Croix although Delville later gravitated to Theosophy. Schwabe produced illustrations for an edition of Baudelaire’s Les Fleurs du Mal, and would have featured in the Baudelaire posts last week if some of those drawings hadn’t appeared here already. The title page was a new find, however, so it’s included below.

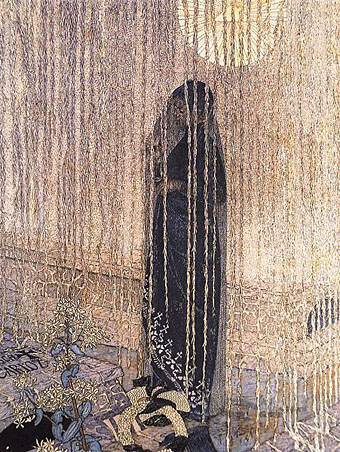

Jour de morts (1890).

La mort du fossoyeur (1895).