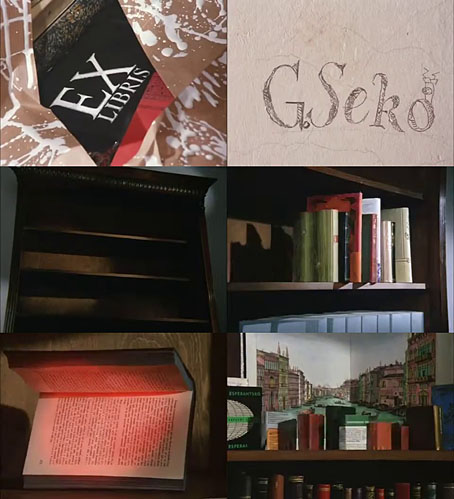

Garik Seko (1935–1994) is an animator whose work I hadn’t encountered before. He was born in Tiflis, Georgia, but worked in Prague where a number of his shorts (this one among them) were made at the Jiří Trnka Studio. Seko’s speciality was the animation of physical objects, in the case of this film a quantity of anthropomorphised books populating the shelves of a bookcase. Jan Švankmajer comes immediately to mind when watching Ex Libris, especially when two philosophy books chew each other to pieces following a vociferous argument. Švankmajer also made films at the Trnka Studio but I’d wary of suggesting an influence in one direction or another when the similarities are superficial ones. Ex Libris was made in 1983, by which time Švankmajer had been animating physical objects (and people) for many years. His own films are more aggressive than Seko’s, usually with a philosophical or Surrealist subtext. Ex Libris may be seen here.

Category: {animation}

Animated films

Nezha Conquers the Dragon King

From an Arabian story with a Chinese theme to a Chinese adaptation of a Chinese story. Nezha Conquers the Dragon King is an hour-long animated presentation of an episode from Chinese mythology, in which Nezha, a magical boy born from a lotus flower, uses his powers to defend his home town and its inhabitants against four destructive dragons. The film was made in 1979 by the Shanghai Animation Film Studio, and directed by Wang Shuchen, Yan Dingxian and Xu Jingda. It was dubbed into English by the BBC for a TV broadcast a few years later, something I never saw at the time but the dubbed version sounds like one to avoid. They also replaced the original score and no doubt cropped the widescreen image as well. The BBC dubbed René Laloux’s marvellous Time Masters for its TV broadcasts in the 1980s but they did at least leave the music alone.

One of my most enjoyable cinematic discoveries of the past year has been the wuxia films of Zhang Yimou: Hero (2002), House of Flying Daggers (2004), and Shadow (2018). Also Curse of the Golden Flower (2006) which is more of a straightforward historical drama for the most part, without any of the displays of balletic martial arts that are a common feature of wuxia films. Nezha Conquers the Dragon King is pretty much a wuxia story for children, with Nezha being a skilled fighter almost from the day he’s born. His feud with the dragons culminates in a battle in which he takes on an army of anthropomorphic animal opponents. (Another common feature of wuxia stories is pitting one or two skilled combatants against a mass of armed men.) The stylised animation, replete with motifs borrowed from traditional paintings, is beautifully rendered througout, while the basic storyline is so similar to Marcell Jankovics’ Son of the White Mare (1981) it’s tempting to wonder whether the Chinese film gave Jankovics the idea for his second feature. Son of the White Mare is based on Hungarian folk tales but it too concerns a magical child (born from a horse rather than a flower) whose super-strength enables him to fight three dragon beings who have been threatening the land. Like their Chinese counterparts, the Hungarian dragons can assume human form, and each has a special power related to a different element. Jankovics’ film was released on blu-ray recently; I ought to watch it again.

Nezha Conquers the Dragon King may be seen here in a print with embedded English subtitles.

Weekend links 812

• RIP Béla Tarr. I came late to Tarr’s films, he’d retired from directing by the time I worked my way through most of his oeuvre in 2019. As I’m always saying: better late than never. What I never expected from reading reviews was the irreducible strangeness at the heart of the later films, as well as their meticulous construction. With regard to the latter, mention should be made of the director’s regular collaborators: Ágnes Hranitzky (wife, editor and co-director), László Krasznahorkai (writer), and Mihály Víg (composer).

More Tarr: “The whole fucking storytelling thing is everywhere the same. That’s why I decided I have to do my movies.” Tarr talking to R. Emmet Sweeney in 2012; and at Criterion, Béla Tarr: Lamentation and Laughter by David Hudson.

• “When [Fela Kuti] first saw Lemi Ghariokwu’s work, he said, ‘Wow!’ Then he plied him with marijuana and asked him to design his album sleeves. The artist recalls their extraordinary partnership – and the day Kuti’s Lagos HQ burned.”

• At Smithsonan Mag: “Hundreds of mysterious Victorian-era shoes are washing up on a beach in Wales. Nobody knows where they came from.”

• At Ultrawolvesunderthefullmoon: The collage art of Wilfried Sätty.

• At the BFI: Leigh Singer selects 10 great Lynchian films.

• At Unquiet Things: The vast luminous art of Andy Kehoe.

• At Dennis Cooper’s it’s another Jan Švankmajer Day.

• New music: Light Self All Others by Tarotplane.

• At I Love Typography: Heart-shaped books.

• At Colossal: Luftwerk.

• Sailin’ Shoes (1972) by Van Dyke Parks | Dead Man’s Shoes (1985) by Cabaret Voltaire | New Shoes (2007) by Angelo Badalamenti.

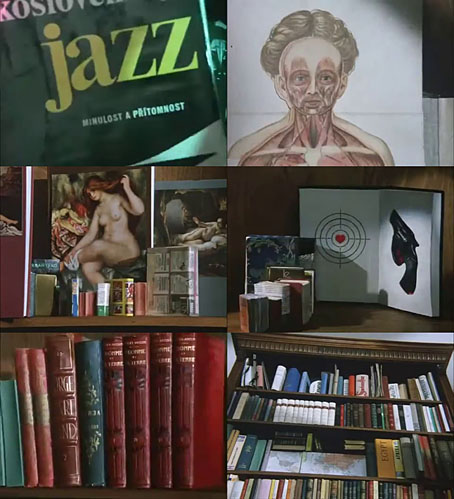

Eclipse and Sunscreen

Gobelins, the French school of film animation, has its own YouTube channel where students post a variety of clips showing technical exercises or, as in the case of this pair of films, complete works. Eclipse (directed by Theo Guignard, Noé Lecombre and Hugo Moreno) and Sunscreen (directed by Xinzhi Ma, Yuan Liu, Yufan Chen and Zixiao Yue) are both science-fiction pieces that are also very short, being more like anecdotes than stories. Of the two I prefer Eclipse but both are very accomplished, and a welcome riposte to the ubiquity of the Pixar house style. Stylistic exercises like these are seldom extended to feature-length (or if they are, they get cancelled like Scavengers Reign) but it’s good to see younger animators following in the footsteps of René Laloux.

And speaking of Laloux, the restored Les Maîtres du temps (Time Masters) was released on blu-ray in France last year. As with many French releases there are no English subtitles but it’s good to know it’s available again. I’m waiting now for a high-definition reissue of Gandahar.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Terra Incognita, a film by Adrian Dexter and Pernille Kjaer

• Arzak Rhapsody

• Fracture by Paul and Gaëtan Brizzi

• The Captive, a film by René Laloux

Weekend links 811

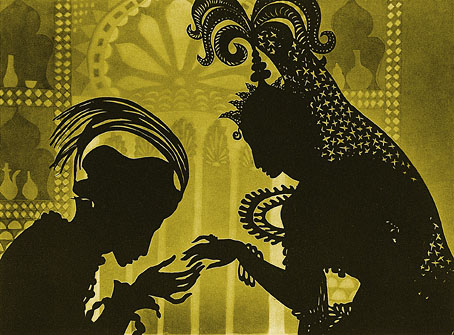

A still from The Adventures of Prince Achmed (1926), a feature-length animated film by Lotte Reiniger.

• Hélice 39 is a speculative-fiction journal (in Spanish) whose current issue includes an article by Marcelo Sanchez: “What did Borges think of Lovecraft?”

• Among the new titles at Standard Ebooks, the home of free, high-quality, public-domain texts: The Maltese Falcon by Dashiell Hammett.

• Old music: Hydrophony For Dagon by Max Eastley & Michael Prime; The Adventures Of Prince Achmed by Morricone Youth.

• Public Domain Review lists some of the writers whose works will enter the public domain this year.

• “Modern Japanese Printmakers celebrates vibrant mid-20th-century innovation“.

• At Nautilus: “Here’s what’s happening in the brain when you’re improvising.”

• At the BFI: Pamela Hutchinson selects 10 great films of 1926.

• New music: The Future Is Now by Pietro Zollo.

• At Dennis Cooper’s: Phil Solomon Day.

• 2026 is the Year of the Fire Horse.

• Runaway Horses (“poetry written with a splash of blood”) (1985) by Philip Glass | Unicorns Were Horses (1996) by New Kingdom | Red Horse (2002) by Jack Rose