The Song of Love (1914) by Giorgio de Chirico.

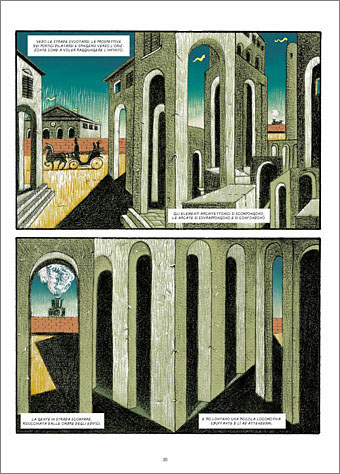

His art studies, begun in Athens, were continued in Munich where he discovered the work of Max Klinger and Arnold Böcklin, not to mention the writings of Friedrich Nietzsche and Arthur Schopenhauer, whose influence is perceptible in the paintings he went on to produce in Florence and Turin. In addition, his melancholy temperament lay behind the works that Guillaume Apollinaire labelled “metaphysical,” works in which elements from the real world (deserted squares and arcades, factory chimneys, trains, clocks, gloves, artichokes) were imbued with a sense of strangeness.

Keith Aspley, Historical Dictionary of Surrealism

The Enigma of a Day (1914) by Giorgio de Chirico.

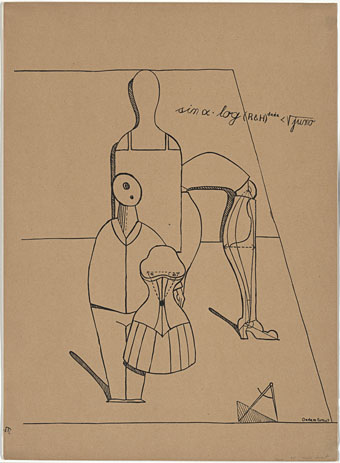

Plate II from Let There Be Fashion, Down With Art (Fiat modes pereat ars) (1920) by “Dadamax Ernst”.

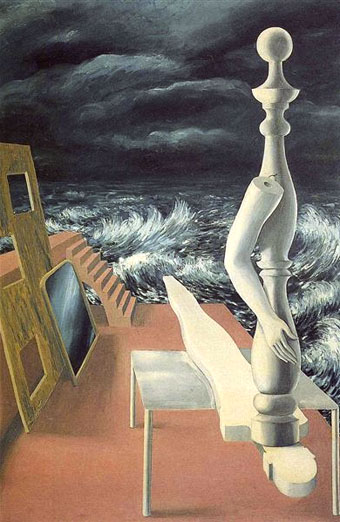

The Birth of an Idol (1926) by René Magritte.

Some time during the latter part of 1923 [Magritte] came face-to-face with his destiny, in the form of a painting by Giorgio de Chirico, who was one of the painters most admired by the Paris Surrealists: Le Chant d’amour (The Song of Love, 1914); to be more precise, a black-and-white reproduction of that painting in the review Les Feuilles libres, a very contrasty reproduction, as Sylvester has it, which only heightened the drama of the outsize objects suspended in the foreground of one of de Chirico’s “metaphysical landscapes”… He was shown it by Lecomte, or Mesens, or both. He was overwhelmed. […] Magritte always spoke of de Chirico as his one and only master. As a rule, he was exceedingly parsimonious in his assessment of other artists, past and present. In his own time, de Chirico (1888–1978) and Ernst (1891–1976) appear as the only two he admired, more or less unconditionally.

Magritte: A Life by Alex Danchev

Sewing Machine with Umbrellas in a Surrealist Landscape (1941) by Salvador Dalí.

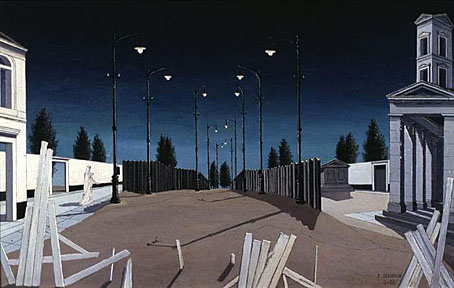

La Ville Luminaire No. 2 (1956) by Paul Delvaux.

The Disquieting Muses (1957) by Sylvia Plath.

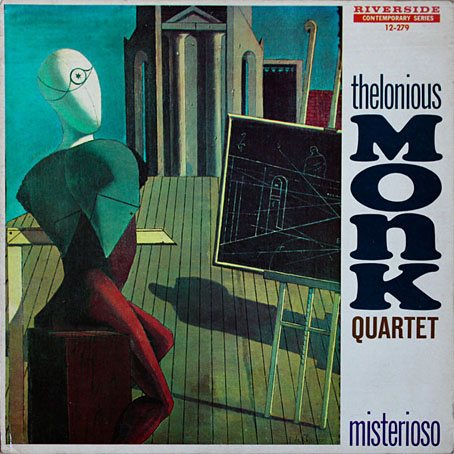

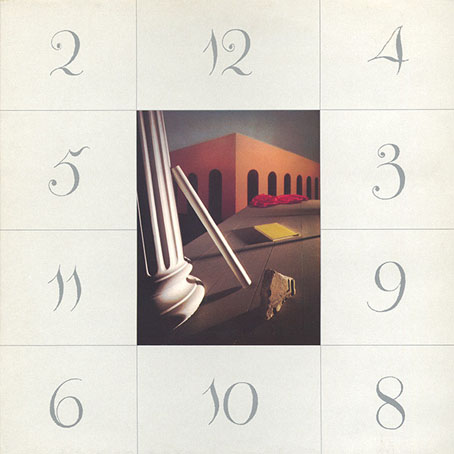

Misterioso (1958) by Thelonious Monk Quartet. Design by Paul Bacon.

The Spider’s Stratagem (1970), directed by Bernardo Bertolucci.

The Spider’s Stratagem is a movie conceived of, written and shot in colour and is evocative of certain paintings by René Magritte or Giorgio de Chirico.

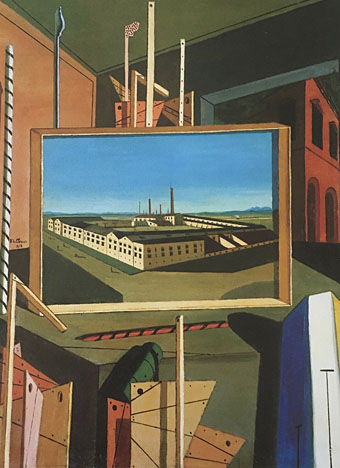

Metaphysical Interior with Large Factory (1916) by Giorgio de Chirico.

Sleeve rear: “Metaphysical view of Factory with album cover.”

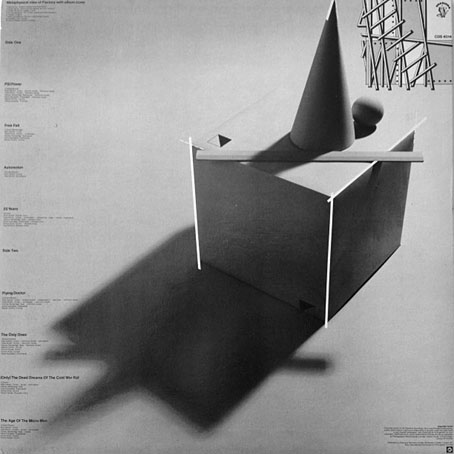

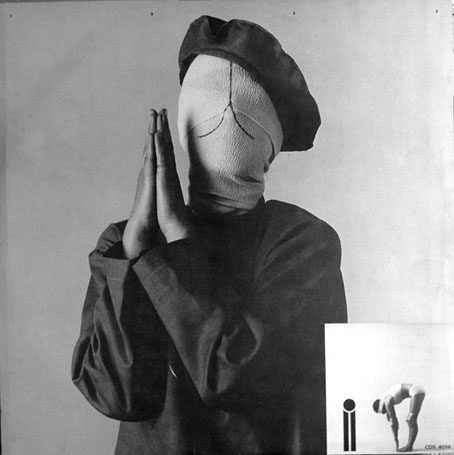

25 Years On (1978) by Hawklords. Design by Barney Bubbles. Photography by Brian Griffin and Chris Gabrin.

Inner sleeve.

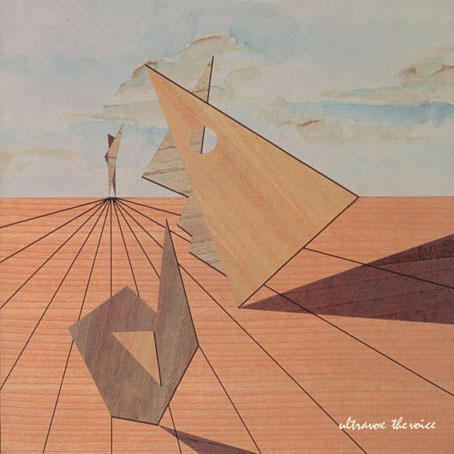

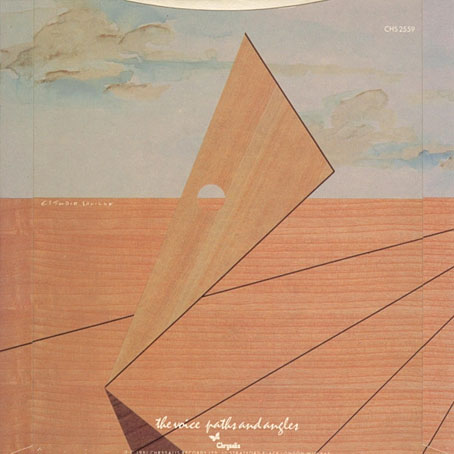

The Voice (1981) by Ultravox. Design by Peter Saville (credited to “Estudio Saville”).

Thieves Like Us (1984) by New Order. Design by Peter Saville/Trevor Key.

Promo video for Loving the Alien (1985) by David Bowie. Directed by David Bowie with David Mallet.

The Red Tower (1913) by Giorgio de Chirico.

The Red Tower (1996) by Thomas Ligotti.

The ruined factory stood three stories high in an otherwise featureless landscape. Although somewhat imposing on its own terms, it occupied only the most unobtrusive place within the gray emptiness of its surroundings, its presence serving as a mere accent upon a desolate horizon. No road led to the factory; nor were there any traces of one that might have led to it at some time in the distant past. If there had ever been such a road it would have been rendered useless as soon as it arrived at one of the four, red-bricked sides of the factory, even in the days when the facility was in full operation. The reason for this was simple: no doors had been built into the factory, no loading docks or entranceways allowed penetration of the outer walls of the structure, which was solid brick on all four sides without even a single window below the level of the second floor.

Surrealista: A Tribute to Giorgio de Chirico for Windows and Mac computers.

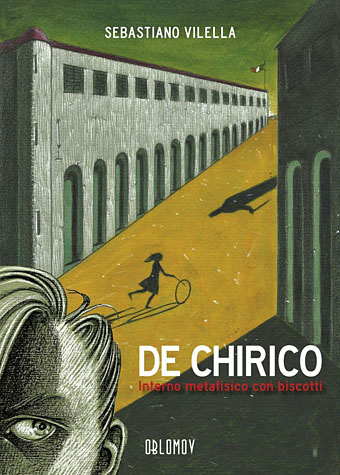

De Chirico – Interno metafisico con biscotti (2020), a romanzo a fumetti by Sebastiano Vilella.

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The Surrealism archive

Previously on { feuilleton }

• The nightingale echo

• Max Ernst’s favourites

• The art of Carel Willink, 1900–1983

That was a great little stroll through art-historical iconography. The receding floor/stage/street motif was prevalent in the 1940’s; I think Bevis Hillier referred to it in “Austerity Binge”. Was de Chirico the origin of it? Of course, there was a lot of commercial appropriation of Surrealism in the ’40s.

And that David Bowie video: I think I caught references to Gilbert and George along with de Chirico in there, but the bigger thing was the 1980s “Orientalism” Bowie reveled in that I can’t imagine anyone getting away with today. This was a fun post!

Yes, I think de Chirico was the origin of the receding plain which Dalí then adopted as a favourite motif. Robert Hughes points out that de Chirico got his tilted angles from the Cubists but they were mostly working with small scenes such as portraits and still lifes. De Chirico turned Cubism into a dream-like nocturnal environment.

And, yeah, Bowie plunders from all over in that video. The glowing light in the mouth is taken from Laurie Anderson’s performances circa 1980.

Giorgio de Chirico was a genius, and his work is still beautiful and haunting centuries after it was created. I can’t believe anyone would say that his paintings are “strange,” or “metaphysical.” They’re simply beautiful and unique.