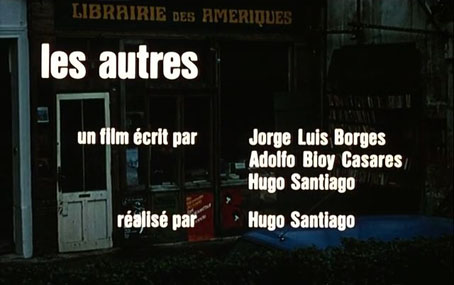

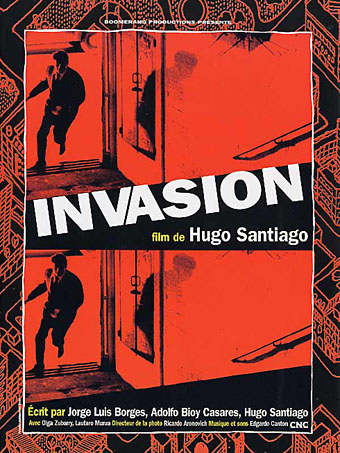

More Borges. Recent posts about the Venerable Jorge had me searching again for a subtitled copy of Hugo Santiago’s Invasion, the feature film he made in Argentina in 1969 from a script co-written with Borges and the latter’s friend and frequent collaborator Adolfo Bioy Casares. Subtitled copies of Invasion are now easier to find than they were when I wrote about the film back in 2014; there’s one here although this wasn’t the copy I was watching at the weekend so I can’t vouch for the quality of the subtitles. As before, this is the précis:

In 1957, a small group of middle-aged men fight a clandestine battle against forces quietly invading and taking control of their city, Aquilea. Enigmatic in its story-telling, Hugo Santiago’s once-lost film obscures the motivations of either side, leaving only a series of moves and counter-moves that evokes past dictatorial oppression and those still to come.

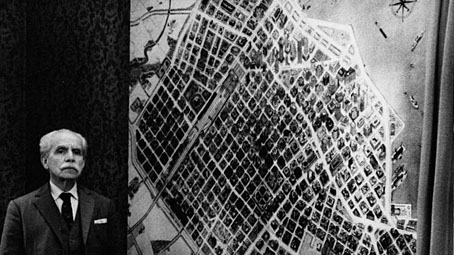

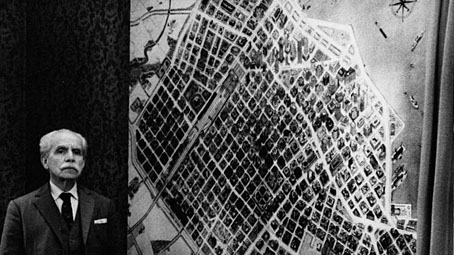

Don Porfirio (Juan Carlos Paz).

“Aquilea” is Buenos Aires masquerading as a fictional city, with a name borrowed from Roman history. For Borges readers the views of the city are fascinating in themselves since they show us the streets and café interiors which are settings for many of the writer’s stories; we also see one of his books, El Hacedor, prominently situated on a shelf. Beyond this, the fictionalising of the city pushes the story away from Argentina’s turbulent political history towards the fantastic and the mythic, as does the lack of any background information about the life-and-death struggle we’re witnessing.

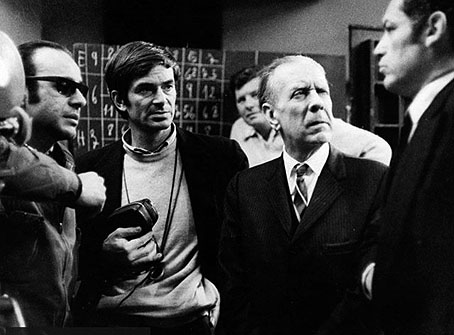

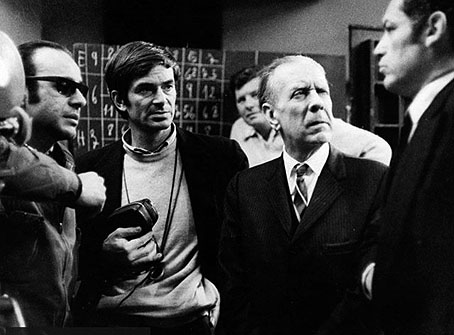

The writer visits the set. Left to right: Hugo Santiago, Ricardo Aronovich, Jorge Luis Borges and Lautaro Murúa.

This was Hugo Santiago’s debut feature, made after several years working in France as an assistant to Robert Bresson. For a debut it’s an impressively assured piece of work, a fast-moving thriller of a type you wouldn’t expect Bioy Casares and Borges to be involved with; less time is devoted to dialogue than there is to gunfights and assassinations. Reviewers tend to compare Invasion to Alphaville but this is misleading; Aquilea may be an invented setting but there’s nothing about the place that’s futuristic or unreal beyond the surreptitious invasion which is being staged and resisted in the midst of an oblivious citizenry. A direct influence was a long-running and very popular Argentine comic strip, Héctor Germán Oesterheld’s The Eternaut, in which the surviving inhabitants of Buenos Aires fight against alien invaders; but this is a typical science-fiction scenario, with most of the human beings wiped out and the survivors battling a variety of monsters. Santiago’s film is more elusive than this, although Lautaro Murúa as Herrera, the leader of the resistance, physically resembles the stern protagonist from the comic. Invasion is deadly serious in a way that Alphaville never is, free of the quotation marks that frame all of Godard’s fictional excursions. The photography by Ricardo Aronovich is the high-contrast chiaroscuro of a late film noir like Kiss Me Deadly, as is the atmosphere of doom, paranoia and escalating urgency; characters are shown continually marching or running towards their destinations. Murúa strides through his scenes with the grim determination of Lee Marvin in Point Blank; in fact Boorman’s film is a better comparison than Alphaville, a spare and elliptical neo-noir that was one of the first Hollywood features to embrace the innovations of the Nouvelle Vague.

The harsh separation between black and white extends to the white raincoats of the invaders and the black suits of the resistance, the latter being directed by Don Porfirio (Juan Carlos Paz), an elderly man who spends most of the film in his apartment where he plans operations while talking to his black cat and drinking maté tea (a South American habit frequently referred to in Borges’ stories that you seldom see on screen). Most surprising of all is the soundtrack by Edgardo Cantón, a musique-concrète assemblage of animal cries, metallic shrieks and electronic tones. The inexplicable presence of these sounds complements the inexplicable nature of the scenario while resisting easy interpretation.

Invasion‘s ambiguities may help the film sidestep an overtly political reading but they were deemed threatening enough by the Argentine dictatorship of the 1970s for the negative to be seized and kept from circulation for many years. (Parts of the film are also disturbingly prophetic: the invaders base their operations—which extend to torture and murder—in the city’s athletic stadium; a few years later similar South American stadia were being repurposed as venues for mass execution.) Restoration work on the film in 1999 led to the copies that circulate today. Borges wouldn’t have seen anything of this during his lifetime, his blindness was almost total by 1969, but we’re more fortunate. If you enjoy unusual thrillers this is one I recommend.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Goodfellow and Borges

• The Rejected Sorcerer

• The Immortal by Jorge Luis Borges

• Borges on Ulysses

• Borges in the firing line

• La Bibliothèque de Babel

• Borges and the cats

• Invasion, a film by Hugo Santiago

• Spiderweb, a film by Paul Miller

• The Library of Babel by Érik Desmazières

• Books Borges never wrote

• Borges and I

• Borges documentary

• Borges in Performance