The first chimes of a period which began in 1912 and will only end with my death, were rung for me by Diaghilev, one night in the Place de la Concorde. We were going home, having had supper after the show. Nijinsky was sulking as usual. He was walking ahead of us. Diaghilev was scoffing at my absurdities. When I questioned him about his moderation (I was used to praise), he stopped, adjusted his eyeglass and said: ‘Astonish me.’ The idea of surprise, so enchanting in Apollinaire, had never occurred to me.

In 1917, the evening of the first performance of Parade, I did astonish him.

This very brave man listened, white as a sheet, to the fury of the house. He was frightened. He had reason to be. Picasso, Satie and I were unable to get back to the wings. The crowd recognized and threatened us. Without Apollinaire, his uniform and the bandage round his head, women armed with pins would have put out our eyes.

Jean Cocteau (again), writing in The Difficulty of Being about the opening night of Parade, the “ballet réaliste” he created for Diaghilev’s Ballets Russes. Erik Satie wrote the music, Léonide Massine choreographed the dance, and Pablo Picasso designed the costumes and decor, with assistance from Giacomo Balla, one of the Italian Futurists. The reception for Parade wasn’t as thoroughly hostile as that received by Le Sacre du Printemps a few years earlier but there was bait enough for the reactionaries, with ragtime quotes in the dance and the music, and an everyday setting in which a group of street performers attempt to summon a crowd to see their show. Other details were overtly avant-garde: some of Picasso’s costumes were more like wearable cardboard sculptures, while Cocteau further antagonised the audience (and the composer) by adding the sounds of a typewriter, siren, pistol and steamship whistle to the music. The most significant response came from Apollinaire when he described the ballet in the programme notes as “une sorte de surréalisme“, giving the world a new word which we still use today.

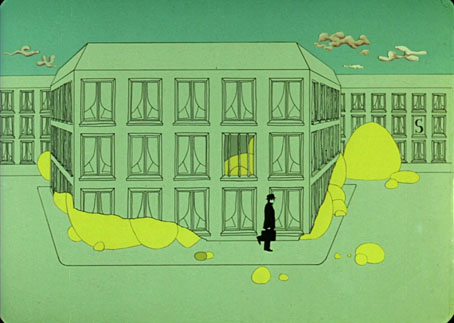

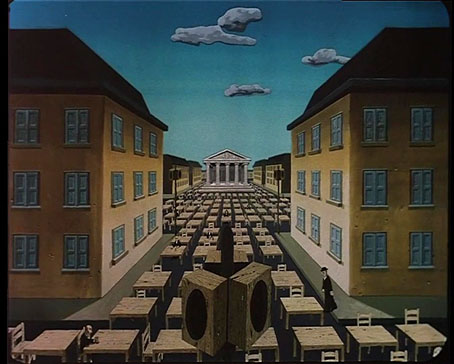

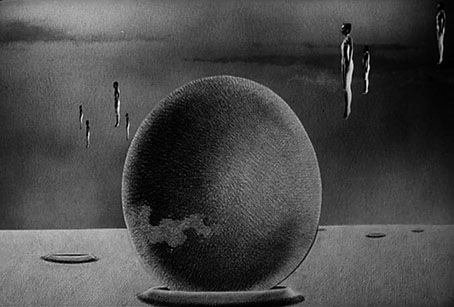

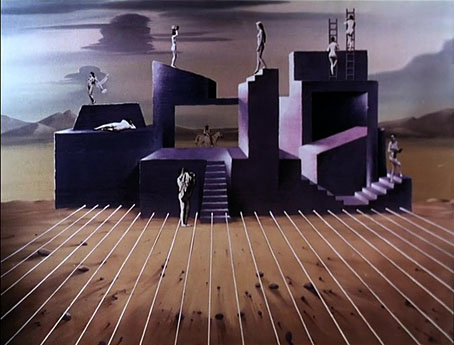

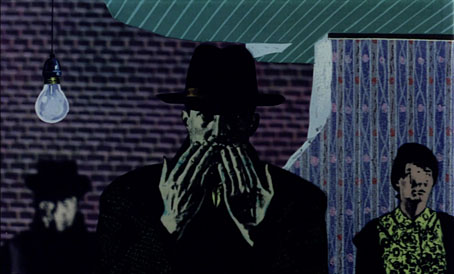

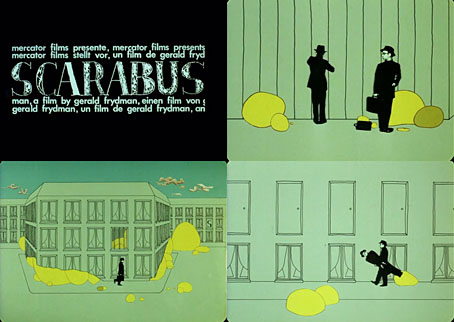

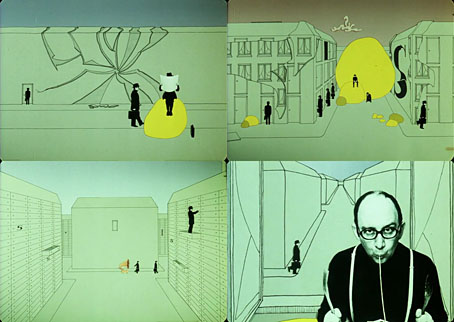

Parade de Satie by Koji Yamamura is an animated presentation of Satie’s music which sees the characters from the ballet—a Chinese magician, a small American girl, the acrobats, a pantomime horse—jumping and dancing around the screen while Satie, Picasso and Cocteau observe the proceedings. It’s a lively and witty film, probably more lively than the ballet itself when the hand-drawn performers are less encumbered by gravity or their unwieldy outfits. Yamamura has directed a single animated feature, Dozens of Norths, and many more shorts like Parade de Satie, including films based on a story by Franz Kafka (A Country Doctor) and the life of Eadweard Muybridge (Muybridge’s Strings). Being a pioneer of motion photography and inventor of the Zoopraxiscope, Muybridge is an attractive subject for animators. The naked figures from his studies of human and animal motion turn up in Terry Gilliam’s Monty Python animations, while Gérald Frydman directed a short biographical film about Muybridge, Le Cheval de Fer, in 1984.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Jean Cocteau: Autoportrait d’un inconnu

• Orphée posters

• Cocteau and Lovecraft

• Cocteau drawings

• Querelle de Brest

• Halsman and Cocteau

• La Belle et la Bête posters

• The writhing on the wall

• Le livre blanc by Jean Cocteau

• Cocteau’s sword

• Cristalophonics: searching for the Cocteau sound

• Cocteau at the Louvre des Antiquaires

• La Villa Santo Sospir by Jean Cocteau