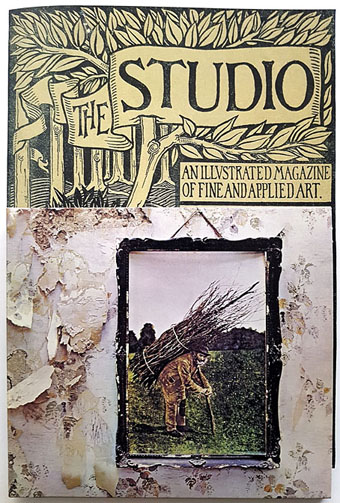

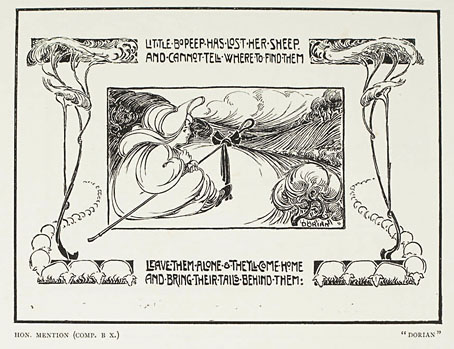

Background graphics by Aubrey Beardsley, 1893.

You’d think by now that everything would be known about an album with a Godzilla-sized cultural footprint like Led Zeppelin IV. I certainly thought so until last week when I turned up the source of something that the more obsessive Zepp-heads have been pondering for years. If this puts a bustle in your hedgerow then read on.

Led Zeppelin’s fourth album has been around now for half a century which means there really is a lot known about every detail of its production. Mysteries that used to confound friends of mine when we were teenagers have long been solved, questions such as what the hell the four symbols assigned to each member of the group actually signified; not only do we know the origin and meaning of those symbols, the enigmatic “Zoso” sigil chosen by Jimmy Page has an entire website dedicated to its various manifestations. We know where the photo on the cover was taken (Birmingham), and why the sleeve is devoid of identification (Page was annoyed with the press reaction to the previous album); we know that the hermit painting inside the gatefold is based on the Tarot card by Pamela Colman Smith, and we also know a great deal about the writing and recording of Stairway To Heaven. Erik Davis logged much of this in his 33 1/3 study of the album, and while he examines the band symbols in some detail he doesn’t say much about the rest of the hand-written inner sleeve beyond this comment:

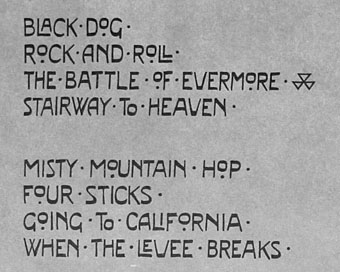

Is there a meaning to the nifty Arts and Crafts typeface that Page lifted for the Stairway To Heaven lyrics on the other side of the sleeve? Or just a vibe?

The source, if not the meaning, of this script has been intriguing Zeppelin fans for many years, but I wasn’t aware of this until I happened to be reading the Wikipedia entry about the album and found myself equally intrigued. The game was afoot, Watson.

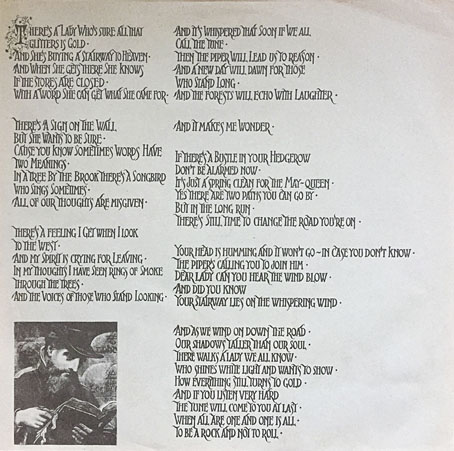

It makes them wonder: the hand-lettered lyrics.

A persistent question you see in fan circles is “What font was used to create X?” People will ask this question even when the design is a one-off, like Syd Mead’s logo for Tron, or something that’s obviously been lettered by hand. Led Zeppelin IV is an album guaranteed to raise the “What font?” question because the lyrics of the group’s most famous song, Stairway To Heaven, cover an entire side of the inner sleeve. On one of the fan forums I was reading someone was eager to identify “the font” because they wanted to apply the words to a bedroom wall. Many more people must have copied out those lyrics since 1971; I once had to do this myself for a female friend who was so besotted with Jimmy Page that she wanted the lyrics in a frame on her own bedroom wall.

According to the Wikipedia entry, Page revealed the source of the lettering to be an issue of The Studio, the British art and design magazine which helped launch Aubrey Beardsley’s career and did much to develop and promote the Art Nouveau style in the 1890s. I’m very familiar with The Studio, many posts here refer to it, and I happen to have a complete collection of issues downloaded from the journal archive at Heidelberg University. Seeing the magazine mentioned in this context immediately made me want to find the design that Page had adopted, but before I started flicking through thousands of pages I looked around to see if any of the Zepp-heads had tried searching for the magazine themselves. Evidently not; all the discussion I’ve seen about the inner sleeve tends to recycle the Wikipedia entry, nobody seems to have bothered looking for copies of the magazine. Okay then…

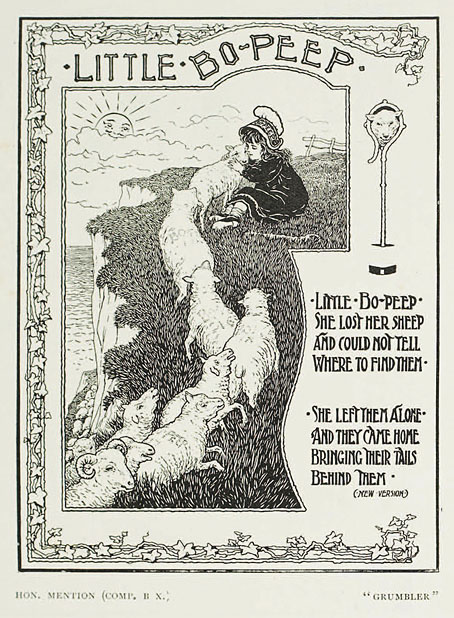

Some three thousand pages later, my mouse-clicking was arrested by this picture in the middle of Volume Thirteen. The articles there date from 1898, and the drawing caught my attention because the lettering is obviously the source of the hand-drawn type on the other side of the inner sleeve (see the track list above), something I didn’t expect to find at all. After recovering from the surprise of this I looked at the page opposite and there was the very thing I was after, another version of the same rhyme lettered in the manner of the Stairway To Heaven lyrics. This was also surprising as well as a little bizarre. I’d been expecting to find something like a page of fin-de-siècle typeface designs, not a collection of nursery rhymes.

Why Little Bo-Peep? And why two illustrations of the same rhyme by different artists? The Studio, like Art et Décoration in France, and Deutsche Kunst und Dekoration in Germany, held competitions for readers who would be tasked with creating designs in the manner of the graphics promoted by the magazine. Many of the entrants to The Studio competitions used pseudonyms, hence the credits on these illustrations to “Dorian” and “Grumbler”. The most surprising thing about the two drawings is that they seem so slight in comparison to the thundering assertiveness of a song like Black Dog, never mind the sheer cultural weight of the album whose design they inspired. I’d flicked through this volume at least once in the past—it also contains the lengthy memorial notice for the recently deceased Aubrey Beardsley—but even if I’d have spotted the lettering before now I doubt I would have connected it with the album. As for the artists, the magazine didn’t reveal the names of its competition entrants so we’ll probably never know the identities of “Dorian” and “Grumbler”.

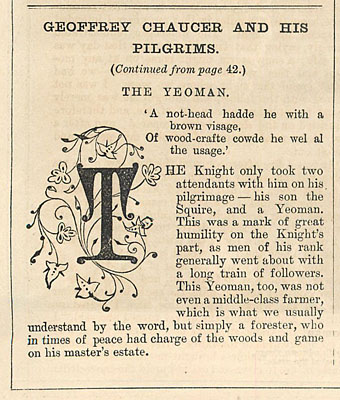

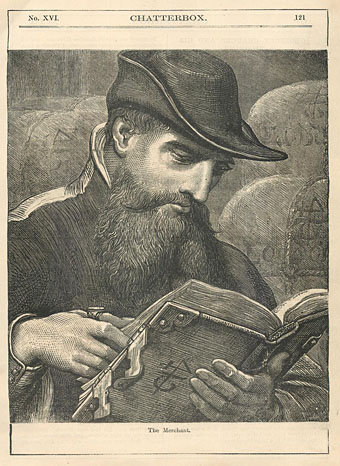

That should have been the end of the matter but there was one last surprise in store. One of the Zeppelin forums reveals the source of the small engraved picture that accompanies the Stairway To Heaven lyric. This isn’t an illustration of an alchemist as I and many other people have previously assumed, but a portrait of the Merchant from Chaucer’s Canterbury Tales. Those curious symbols are medieval merchant’s marks, something that Jimmy Page must have known if, as seems likely, he chose the picture himself. The symbols have been made bolder on the inner sleeve which suggests that the picture was selected for the symbols more than anything else; they work as a visual complement to the symbols assigned to the musicians. The engraving was one of several portraits of Chaucer’s characters that accompanied a condensed recounting of the tales in a popular Victorian children’s magazine, The Chatterbox. Once again, none of the Zepp-heads had gone looking for the original source but I knew that a collection of Chatterbox annuals had arrived recently at the Internet Archive so I sought out the relevant issue.

Having found the illustration in a matter of minutes I was flicking through the rest of the book only to be stopped in my tracks once again by the sight of a decorated capital on page 55. It’s not an exact match but this seems to be the source for the drop cap on the Stairway To Heaven lyric. The album’s design is credited to Graphreaks, an outfit who did a lot of work for the music business in the 1970s. It’s easy to imagine them being given the reference copies of The Studio and The Chatterbox then borrowing the decorated capital while they were creating the artwork; it’s the kind of thing I’d do myself.

So there you have it. To the album’s unique mélange of rock’n’roll, blues, Tolkien, folk rock and occultism can be added nursery rhymes and The Canterbury Tales. Erik Davis notes the fervid speculation that follows anything Zeppelin-related so I can imagine this post adding fuel to future theorising. If the Zeppelin exegetes require a starting point then they might consider that the nursery rhyme isn’t such an odd connection when Robert Plant ends Gallows Pole by singing “See-saw, Margery Daw…” As for those sheep, the more pious forms of Victorian art often used sheep as symbols of Christian worshippers; William Holman Hunt did this in on a couple of occasions, notably in his religious allegory Our English Coasts (aka Strayed Sheep) (1852). Given this, “Grumbler’s” sheep (which also happen to be on a cliff) may be taken as strayed worshippers returning to the church, ascending the grassy stairway to Heaven…

I’m not being serious, of course. You’d be hard-pressed to reconcile Jimmy Page’s occult preoccupations with this kind of Victorian moral instruction. Shortly after Led Zeppelin IV was released Page opened an occult bookshop in London which he named The Equinox after Aleister Crowley’s multi-volume magical treatise. In one of those volumes, Book 4 aka Magick, Crowley shows how even the most innocent texts may yield “hidden” occult meanings if read with sufficient ingenuity; an instruction in magical interpretation and also, perhaps, a warning against the hazards of apophenia. And what texts does Crowley use? A collection of nursery rhymes, the second one of which is the story of Little Bo-Peep.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• The art of Pamela Colman Smith, 1878–1951

• William Rimmer’s Evening Swan Song

The Bo-Peep Font (hereby ‘christen’d’) NEEDS be incorporated in some bumper book of a magick to complete/widen the circle–

just saying ;)

Looking forward to a black waterside* if not white summer,

TjZ

>https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kJQ_rJR3yCs

*Credit Where Due to Bert Jansch

Adapting the Bo-Peep script would certainly be a possibility even though most people would think of it as “The Stairway To Heaven lettering”.

I’d not seen that performance before. Wow…thanks! I was watching the Page and Plant No Quarter concert again a few days ago. Always liked that one for the different arrangement of the songs, especially all the Egyptian orchestra stuff at the end. My late keyboard-playing friend Nik Green was on an album that Roy Harper and Jimmy Page made in the 1980s. I’ve never heard it but it doubt it’ll be up to that standard.

My Wife & I saw Page & Plant twice–the first with the Egyptian orchestra live. My favorite versions of Zep 3 songs are forever those…She interviewed John Paul Jones separately another time.

Fans at this domicile…

In my Alternative Reality: Brian Jones is still alive and stages concerts with the Pipes of Jajouka…

Let Me Dream If I Want To,

TjZ

Fascinating reading, especially with the esotericism, even if this post made me listen to “Stairway to Heaven” for the first time ever (to my knowledge). Thank you.

Better late than never! This was the first Led Zeppelin album I heard. It’s still my favourite.

Thanks for this ! On the nursry rhyme issue, Robert Plant on at least one occassion improvised on ‘Here we go ’round the mulberry bush’ during a performance of Dazed & Confused, ‘Little Beau Peep’ would have fitted just as well, perhaps ?

I’ve got a few Zeppelin bootlegs but none of them feature anything like that! Bo-Peep seems far too innocent next to all those songs about unbridled lust and men with swords. That said, the connection makes the album seem deeper and stranger than it was already.

I had a listen again afterwards and it’s actually from a performance of ‘How Many More Times’ (it’s just a throwaway ad-lib during the improvisation, Filmore West 1969). Yes, I agree about the album; these were always the elements that lifted them so far beyond similar groups that made LZ so attractive. One of Robert Plant’s favourite albums of the time was apparently The Hangman’s Beautiful Daughter (Incredible String Band), and he and Page & JPJ were admirers of Bert Jansch. Maybe a felt connection between folk-song and children’s rhymes catalysed the bustling hedgerows & Beau Peep whimsy ?

If it’s that early then it’s possible that it may be referring to Here We Go Round The Mulberry Bush by Traffic, a theme song the group recorded a year before for the not-very-good film of the same name. Maybe…

Page & Plant’s folk interests definitely explain the Arts & Crafts design connection. It makes more sense for them than the Pop Art-styled design of the previous album. I think that’s a clever design on the whole but it doesn’t really suit the album.