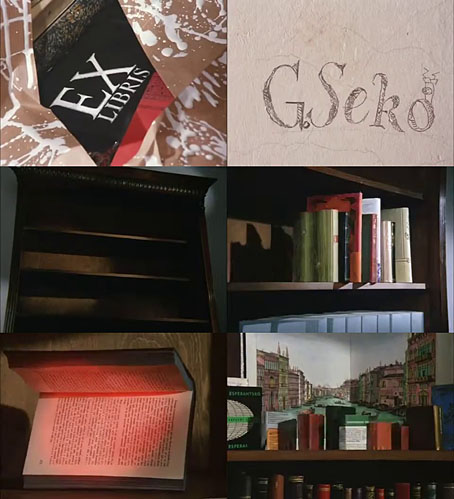

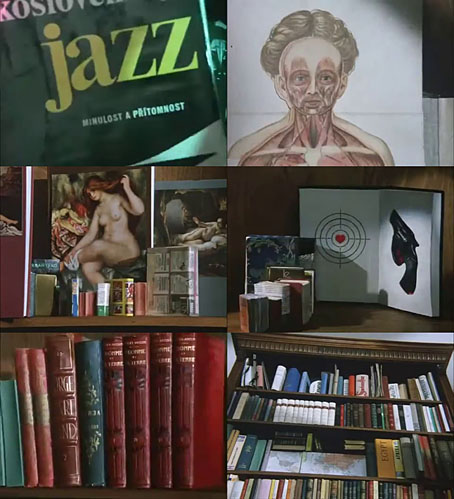

Garik Seko (1935–1994) is an animator whose work I hadn’t encountered before. He was born in Tiflis, Georgia, but worked in Prague where a number of his shorts (this one among them) were made at the Jiří Trnka Studio. Seko’s speciality was the animation of physical objects, in the case of this film a quantity of anthropomorphised books populating the shelves of a bookcase. Jan Švankmajer comes immediately to mind when watching Ex Libris, especially when two philosophy books chew each other to pieces following a vociferous argument. Švankmajer also made films at the Trnka Studio but I’d wary of suggesting an influence in one direction or another when the similarities are superficial ones. Ex Libris was made in 1983, by which time Švankmajer had been animating physical objects (and people) for many years. His own films are more aggressive than Seko’s, usually with a philosophical or Surrealist subtext. Ex Libris may be seen here.

Tag: Jan Švankmajer

Weekend links 812

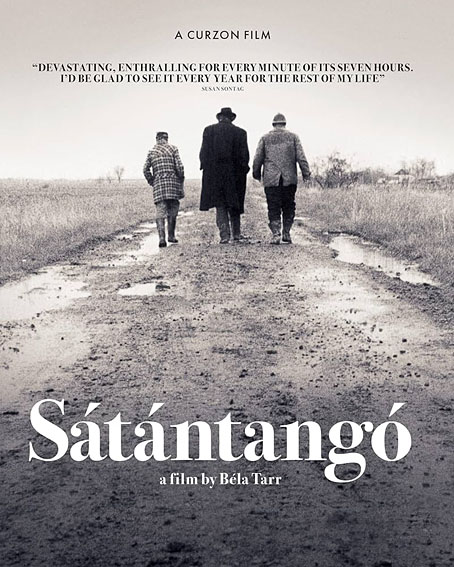

• RIP Béla Tarr. I came late to Tarr’s films, he’d retired from directing by the time I worked my way through most of his oeuvre in 2019. As I’m always saying: better late than never. What I never expected from reading reviews was the irreducible strangeness at the heart of the later films, as well as their meticulous construction. With regard to the latter, mention should be made of the director’s regular collaborators: Ágnes Hranitzky (wife, editor and co-director), László Krasznahorkai (writer), and Mihály Víg (composer).

More Tarr: “The whole fucking storytelling thing is everywhere the same. That’s why I decided I have to do my movies.” Tarr talking to R. Emmet Sweeney in 2012; and at Criterion, Béla Tarr: Lamentation and Laughter by David Hudson.

• “When [Fela Kuti] first saw Lemi Ghariokwu’s work, he said, ‘Wow!’ Then he plied him with marijuana and asked him to design his album sleeves. The artist recalls their extraordinary partnership – and the day Kuti’s Lagos HQ burned.”

• At Smithsonan Mag: “Hundreds of mysterious Victorian-era shoes are washing up on a beach in Wales. Nobody knows where they came from.”

• At Ultrawolvesunderthefullmoon: The collage art of Wilfried Sätty.

• At the BFI: Leigh Singer selects 10 great Lynchian films.

• At Unquiet Things: The vast luminous art of Andy Kehoe.

• At Dennis Cooper’s it’s another Jan Švankmajer Day.

• New music: Light Self All Others by Tarotplane.

• At I Love Typography: Heart-shaped books.

• At Colossal: Luftwerk.

• Sailin’ Shoes (1972) by Van Dyke Parks | Dead Man’s Shoes (1985) by Cabaret Voltaire | New Shoes (2007) by Angelo Badalamenti.

The Hand, a film by Jiří Trnka

Regular readers may have noticed that Jiří Trnka’s name has been written here with all the Czech accents intact, something that hadn’t been possible until a few days ago thanks to a database coding fault. This had long been the case with accents like those used in Czech, Polish, Turkish, Japanese, and other languages, to my endless frustration. I’ll spare you the technical details but the solution, which I resolved at the weekend, turned out to be easier than I expected, as a result of which I’ve been going back through posts adding accents to names which until now had been incomplete.

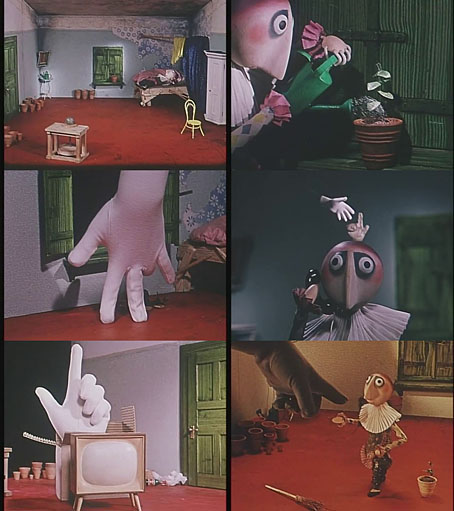

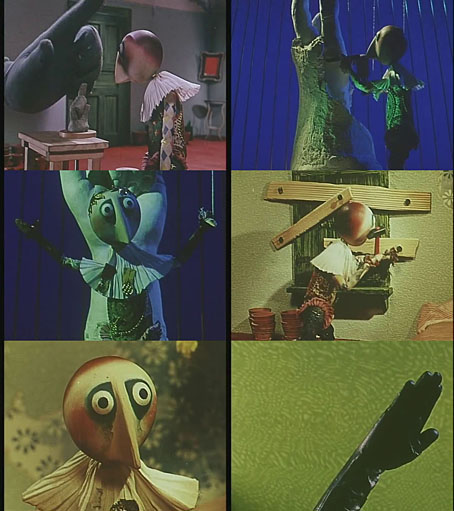

Jiří Trnka (1912–1969) came to mind while I was restoring the accents for Jiří Barta; both men are Czech animators, with Barta having been mentioned here on many occasions. Trnka was one of the founders of the Czech animation industry whose puppet films aren’t always to my taste but I thought I might have mentioned The Hand (1965) before now. This was Trnka’s final film, and one of his most celebrated for its wordless presentation of a universal theme: the freedom of the artist in the face of authoritarian demands. Many of Trnka’s previous films had been stop-motion puppet adaptations of fairy tales which lends The Hand a subversive quality when the scenario seems at first to be pitched in a similar direction. The artist character is a typical Trnka puppet with a persistently smiling face who spends his time in a single room making flowerpots with a potter’s wheel. “The hand” in this context refers both to the manual nature of the potter’s craft as well as to the huge gloved appendage that forces its way into the room demanding that the pots be abandoned in favour of hand-shaped sculptures. The resulting battle of wills shows the strengths of animation in delivering a potent visual metaphor.

Trnka’s message at the time of the film’s release was especially pertinent for the Soviet satellite nations where the promise of post-war Communism had been corrupted by decades of repressive governments, a situation that Jan Švankmajer bitterly addressed in The Death of Stalinism in Bohemia. Trnka isn’t as savage as Švankmajer but his message is still an ironic one, and may have been fuelled by an equivalent bitterness. Trnka’s career was bookended by films showing the struggle of assertive individuals against authoritarian oppression, but in the first of these, The Springman and the SS (1946), the contest is between a Czech chimney-sweep and the Nazi occupiers. The Hand could only be taken by Czech viewers as being aimed at their own oppressive government, and as such may be seen as Trnka’s contribution to the Czech New Wave, especially those films (Daisies, The Cremator) that the same government regarded as politically subversive or otherwise harmful. The Hand, like The Cremator, was withdrawn from distribution a few years after its release. Jiří Barta is a very different director to Trnka but Barta’s The Vanished World of Gloves (1982) features a dystopian sequence showing a fascist world of marching hands which looks like a homage to Trnka’s film. Watch The Hand here.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Jiří Barta: Labyrinth of Darkness

• Jiří Barta’s Pied Piper

Weekend links 745

Eros (1905) by Julius Kronberg.

• At the Internet Archive (for a change): All 15 episodes (with English subs) of Návštevníci (The Visitors, 1983/84), a Czech comedy TV serial about time travellers visiting the present day. Directed by Jindrich Polák, better known for the serious science fiction of Ikarie XB-1 and another time-travelling comedy, Tomorrow I’ll Wake Up and Scald Myself with Tea. The main interest for this viewer is the involvement of Jan Švankmajer who creates collage animation for the first episode while animating food and other objects in later episodes. This was the period when Švankmajer was mainly working as an effects man at the Barrandov Studios after the Communist authorities had put a stop to his film-making. Even with Švankmajer’s involvement I’m not sure I can endure 450 minutes of Czech wackiness but it’s good to keep finding these things.

• “…for the melomaniac who wasn’t in and around Bristol in the 1980s or 90s, the term [trip hop] simply opens the door to a whole universe of music that blurs the lines between so many styles in a way that is still compelling three decades on.” Vanessa Okoth-Obbo on the 30th anniversary of Protection by Massive Attack.

• Coming soon from Strange Attractor: Moon’s Milk: Images By Jhonn Balance, compiled by Peter Christopherson & Andrew Lahman.

For some in Ireland, [The Outcasts] is a dim but impressive memory, glimpsed on late-night television during its only broadcast in 1984. The Outcasts over the decades became a piece of Irish cinema legend, less seen and more peppered into conversations revolving around obscure celluloid. The Irish Film Institute describes this film as “folk horror”, a phrase I find too liberally applied these days to just about anything featuring sticks, rocks, and goats or set in the countryside. The Outcasts does not necessarily strive for the ultimate unified effect of horror. Instead, this film is of a rarer breed, more akin to Penda’s Fen (1974) in its otherworldly ruminations. I’ve come to prefer the phrase “folk revelation” as perhaps a more accommodating description for these sorts of stories. Whatever the case, I hope you get to see this remarkable film.

Brian Showers discussing the contents of The Green Book 24, newly published by Swan River Press. The Outcasts has just been released on blu-ray by the BFI

• Still casting a spell: Broadcast’s 20 best songs – ranked!

• New music: Earthly Pleasures by Jill Fraser.

• At Dennis Cooper’s: John Carpenter‘s Day.

• RIP Maggie Smith.

• The Visitors (1981) by ABBA | Two Different Visitors (2003) by World Standard & Wechsel Garland | We Have Visitors (2010) by Pye Corner Audio

Magic Lantern: A Film about Prague

There are many documentary films about the city of Prague but Magic Lantern is the only one written and presented by playwright Michael Frayn. Very good it is too, a personal view of the city’s political and cultural history which takes in the usual names and subjects: Rabbi Loew and his Golem, Emperor Rudolf II, Rudolf’s alchemists, artists and scholars, photographer Josef Sudek, the ubiquitous Franz Kafka, puppets, automata, and so on. While Frayn discusses the Communist and post-Communist periods there’s a brief clip of Jan Švankmajer’s The Death of Stalinism in Bohemia.

Frayn’s film was directed by Dennis Marks, and broadcast in 1993 as part of the BBC’s long-running Omnibus strand. (There’s a further Švankmajer connection in the person of executive producer Keith Griffiths whose Koninck company produced this film at a time when they were also helping Svankmajer make his features.) Magic Lantern wasn’t the only film that Marks and Frayn made together, and not their first metropolitan essay either. Imagine a City Called Berlin (1974) is a portrait of the former capital of Germany during its Cold War isolation; there’s also The Mask of Gold: A Film about Vienna (1977), and Jerusalem: A Personal History (1984), all of which may be seen at The Dennis Marks Archive. My complaints about YouTube are copious enough to paper the walls of the Hradčany, but the site is at its best when it provides this kind of haven for television history that would be impossible to find elsewhere.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Le Golem, 1967

• Gustav Meyink’s Prague

• Stone Glory, a film by Jirí Lehovec

• The Face of Prague

• Josef Sudek

• Liska’s Golem

• Das Haus zur letzten Latern

• Hugo Steiner-Prag’s Golem

• Karel Plicka’s views of Prague