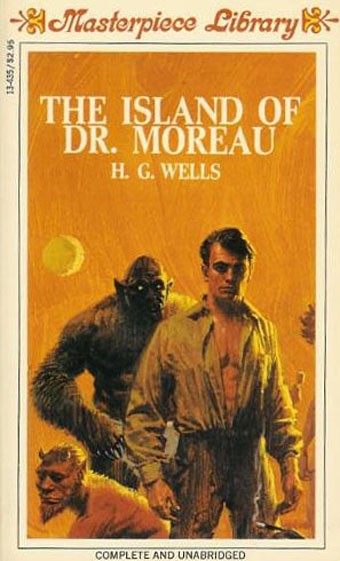

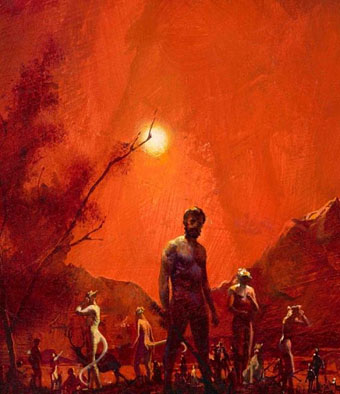

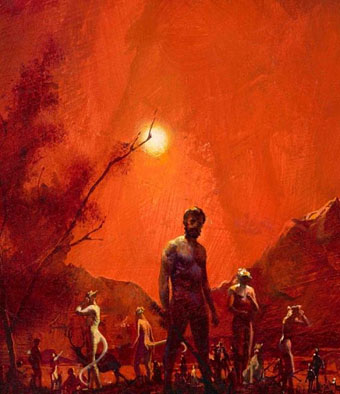

Painting by Paul Lehr for the Berkley Highland paperback (1970).

The Island of Doctor Moreau is one of those Victorian novels everyone thinks they know well enough from various film or television adaptations, even when those adaptations have accreted a layer of misconception around the story. In the case of HG Wells’ novel we have The Island of Lost Souls (1932), which the author loathed for its vulgarisations, and which he helped get banned in Britain for many years; the 1977 film directed by Don Taylor which nobody seems to have a good word for; and Richard Stanley’s 1996 adaptation which might have been worthwhile if he hadn’t been kicked off his own film shortly after shooting began. These films may not distort Wells’ novel as much as the numerous adaptations of Dracula, and Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde, but they still present a skewed impression of a book which is stranger and more disturbing than any screen version.

Wells’ story purports to be the written account of one Edward Prendick who finds himself on Moreau’s remote island after a shipwreck. The bare bones of the story are familiar: Prendick is rescued by Moreau’s alcoholic assistant, Montgomery, and ends up on the island against the doctor’s wishes. The story deviates from the films very quickly by introducing a setting that’s commonplace in Victorian literature but which Hollywood abhors: the all-male enclave. The Island of Lost Souls put “Edward Parker” on the island with his fiancée but went further (to the outrage of Wells and the British censors) by adding a sexy Panther Woman to the menagerie with whom Moreau encourages Parker to mate. There are women among the “Beast People” in Wells’ novel but we’re assured that they’re as grotesque as their male counterparts.

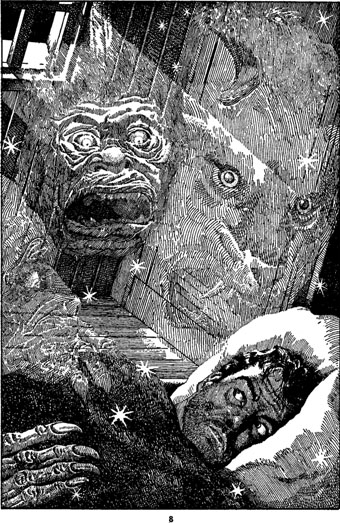

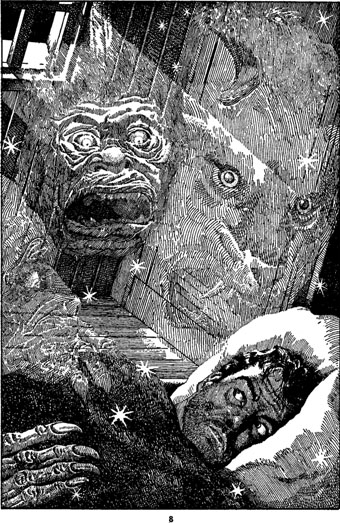

Illustration by Lawrence Sterne Stevens (aka Lawrence) for Famous Fantastic Mysteries, October 1946.

And here we have the second major difference between novel and films: given the limitations of makeup effects—not to say the limitations of the human body—it’s no surprise that the Beast People in the films tend to be like Star Trek aliens, mostly humanoid with a variety of different facial features. Stan Winston’s effects in the 1996 film were the most successful, and were aided considerably by casting a range of actors of different sizes and shapes. All the films tend to present single types, however: wolf-man, cat-woman, bear-man, etc. Wells was writing in 1896 yet his imagination had already brought him this far:

The two most formidable Animal Men were my Leopard-man and a creature made of hyena and swine. Larger than these were the three bull-creatures who pulled in the boat. Then came the silvery-hairy-man, who was also the Sayer of the Law, M’ling, and a satyr-like creature of ape and goat. There were three Swine-men and a Swine-woman, a mare-rhinoceros-creature, and several other females whose sources I did not ascertain. There were several wolf-creatures, a bear-bull, and a Saint-Bernard-man. I have already described the Ape-man, and there was a particularly hateful (and evil-smelling) old woman made of vixen and bear, whom I hated from the beginning. She was said to be a passionate votary of the Law. Smaller creatures were certain dappled youths and my little sloth-creature. But enough of this catalogue.

Later on Moreau has this to say:

“The fact is, after I had made a number of human creatures I made a Thing—” He hesitated.

“Yes?” said I.

“It was killed.”

“I don’t understand,” said I; “do you mean to say—”

“It killed the Kanaka—yes. It killed several other things that it caught. We chased it for a couple of days. It only got loose by accident—I never meant it to get away. It wasn’t finished. It was purely an experiment. It was a limbless thing, with a horrible face, that writhed along the ground in a serpentine fashion. It was immensely strong, and in infuriating pain. It lurked in the woods for some days, until we hunted it; and then it wriggled into the northern part of the island, and we divided the party to close in upon it. Montgomery insisted upon coming with me. The man had a rifle; and when his body was found, one of the barrels was curved into the shape of an S and very nearly bitten through. Montgomery shot the thing. After that I stuck to the ideal of humanity—except for little things.”

Continue reading “The Island of Doctor Moreau”