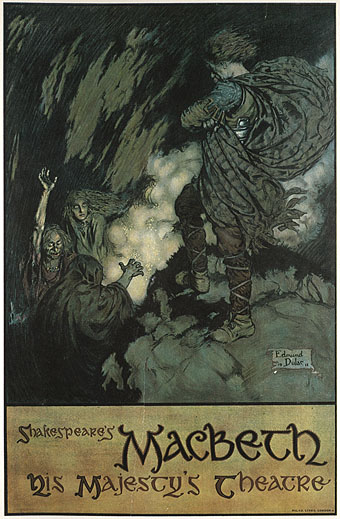

Poster by Edmund Dulac (1911).

This month sees a profusion of events marking the 400th anniversary of Shakespeare’s death so here’s my contribution, a rundown of Macbeths-I-have-seen on screen and stage. I’ve mentioned before that Macbeth and The Tempest are my favourite Shakespeare plays, two dramas concerned with magic of very different kinds. Macbeth is the more popular play, not least for being the more easily adaptable: the supernatural dimension may not suit every circumstance but the themes of treachery, fear, paranoia and a murderous struggle for power are universal. This list contains a wide range of adaptations but there are many film versions I’ve yet to see, including the most recent directed by Justin Kurzel.

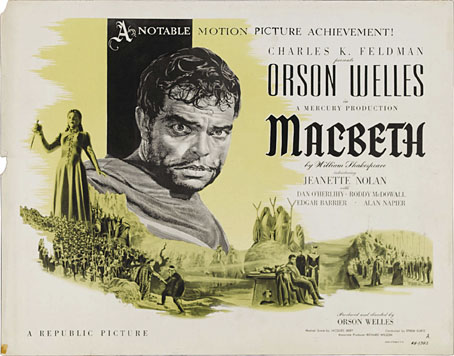

Macbeth (1948), directed by Orson Welles

Orson Welles as Macbeth

Jeanette Nolan as Lady Macbeth

I think the Welles adaptation was the first Macbeth of any kind that I saw so it’s fitting that it begins this chronological list. Famously shot over three hectic weeks on the sound stages of Republic Studios, and with sets made from props previously used in cheap westerns, the result is often eccentric. I’ve a lot of time for Welles as a director but this is one film of his that I’ve never enjoyed very much. His theatre performances (and productions) of Shakespeare began at school, and he was seldom precious with the texts: Chimes at Midnight is a fusion of several different plays while this version of Macbeth uses the same doctored script that he directed for the Voodoo Macbeth in Harlem in 1936. I don’t mind some editing—short scenes such as the witches’ meeting with Hecate are often excised—but some of Welles’ changes are made to support his belief that the witches are directly responsible for Macbeth’s actions, a theory I don’t agree with, and which I’ve never seen given credence elsewhere. This explains oddities such as the appearance of the witches at the very end of the film delivering words from the beginning of the play: “Peace! The charm’s wound up.”

Worse than this is the decision to have most of the cast speaking with vague Scottish accents (a “burr” Welles called it), something that would work with a Scottish cast but which courts disaster with a group of Americans working in haste. The accents may be warranted by the setting but the words of the play are English ones, free of common Scottish colloquialisms such as “ken”, “bairn” and the like. On the plus side, it’s good to see Harry Lime-era Welles performing Shakespeare, and the mist-shrouded production has a barbaric quality that Jean Cocteau appreciated. The forked staff that each witch carries is a detail that I’ve borrowed for drawings on a number of occasions.

Joe MacBeth (1955), directed by Ken Hughes

Paul Douglas as Joe MacBeth

Ruth Roman as Lily MacBeth

The play reworked as a cheap gangster picture set in the Chicago of the 1930s but made in Britain with a partly American cast. I’ve only seen this once (and many years ago) but I recall it being pretty ludicrous, not least for another accent problem with the English actors doing bad impersonations of Chicago hoodlums. Anyone who grew up watching the Carry On comedy films has a hard time taking Sid James seriously in heavy roles, and here he plays the Banquo character, “Banky”. Joe MacBeth is chiefly notable today for being the first entry in the Macbeth-as-gangster sub-genre; after this there was Men of Respect (1990), Maqbool (2003, an Indian film set in Mumbai), and Macbeth (2006, an Australian film set in Melbourne), none of which I’ve yet seen.