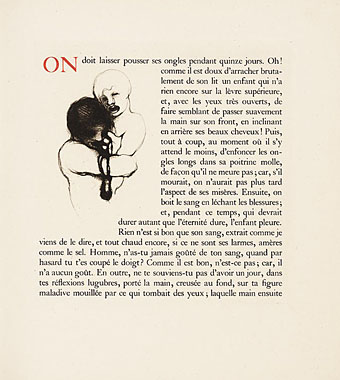

Calling this 1927 edition “illustrated” perhaps stretches the point seeing as Frans De Geetere’s illustrations are rather more minimal and restrained than you’d expect for Lautréamont’s proto-Surrealist masterwork. The Koopman Collection’s page for this book lists 65 Geetere’s etchings but only shows a handful. I’d like to see more of these even if the samples here are representative, Les Chants de Maldoror being a book more deserving of illustration than most.

Frans De Geetere (1895–1968) was Belgian and there’s a Symbolist lineage in this work with his naming Fernand Khnopff and other Belgian Symbolists as influences. He was also a friend of the wealthy arts patron Harry Crosby whose note about the artist promises more than the artwork here delivers:

The darkness of the forest where he was born, the sombre curriculum of the monks together with the rich darkness of ecclesiastical music, the spark of revolt kindled at the Academy of Brussels and whipped into a flame of hatred by the frescoes his father compelled him to paint in the neighboring churches, his first escape (if artists can be said to escape), the year of hunger whitewashing the walls of houses (le soleil contre le mur blanc) and, at nineteen, night duty as guardian in a maison de fous, these were, for M. Frans de Geetere, the foundation stones of that strange building men call the soul. In the madhouse he worked at his painting by day, and by night snatched unsettled hours of sleep, and in this environment developed those queer, abnormal faces that stare out at us from the pages of Maldoror. …And if “Lautreamont has liberated the imagination and dispelled our fear to enter into darkness” as Mr. Jolas so significantly remarked, M. de Geetere with a smoldering rage and fearlessness of creation followed the poet into darkness–“into the occult beyond” to quote Mr. Jolas again, “where new and demonic visions” (I am reminded of Beardsley and Redon and Alastair) “people our solitude.”

Elsewhere on {feuilleton }

• The illustrators archive

• The etching and engraving archive

Previously on {feuilleton }

• The art of Sibylle Ruppert

• Maldoror illustrated