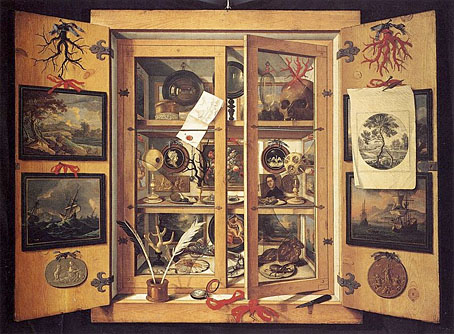

Cabinet of Curiosities (c. 1690s) by Domenico Remps.

• “…the human voice is an astonishing landscape”. Jeremy Allen on Desert Equations: Azax Attra (1986) by Sussan Deyhim & Richard Horowitz, an album which is being reissued by Crammed Discs with bonus tracks and an inexplicably rearranged track list. Good as it is, their follow-up release from 1996, Majoun, is even better, and might be better known if it hadn’t been so thoroughly abandoned by Sony Classical.

• “On view through May 29, By Her Hand: Artemisia Gentileschi and Women Artists in Italy, 1500–1800 showcases masterpieces done by 17 Italian women to make the case for a broader view of women’s participation in the Italian Renaissance.” Nora McGreevy reports.

• “We had a far more profound effect on society than we really understood, and some of us paid for that”: Jane Lapiner and David Simpson of the San Francisco Diggers talking to Jay Babcock in another installment of Jay’s verbal history of the hippie anarchists.

• “Close your eyes and you could almost imagine it’s the muffled screams of a ghost trapped in a bottle.” Daryl Worthington on 25 years of The Ballasted Orchestra by Stars Of The Lid.

• More Dangerous Visions and New Worlds: Mike Stax talks with Michael Moorcock about music, science fiction, politics, and their intersections in the 1960s.

• “Cormac McCarthy to publish two new novels.” Oboy oboy.

• At Dennis Cooper’s: Larry Gottheim Day.

• Metal Machine Music For Airports

• Music For Meditation I (1973) by Eberhard Schoener | Music For Evenings (1980) by Young Marble Giants | Music for Twin Peaks Episode #30 (Part I) (1996) by Stars Of The Lid