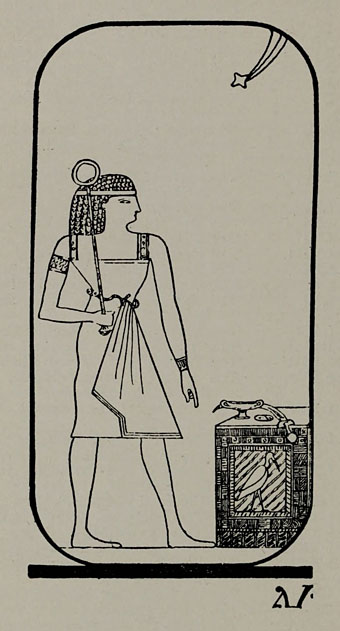

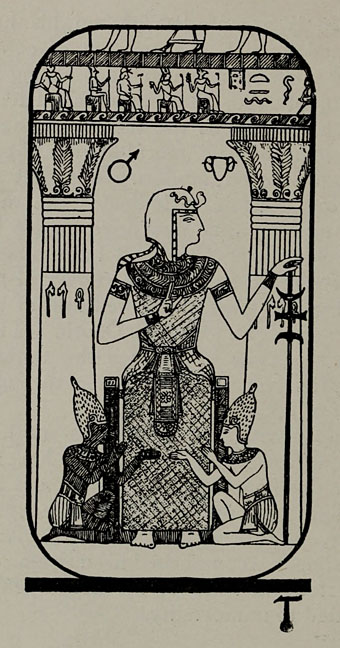

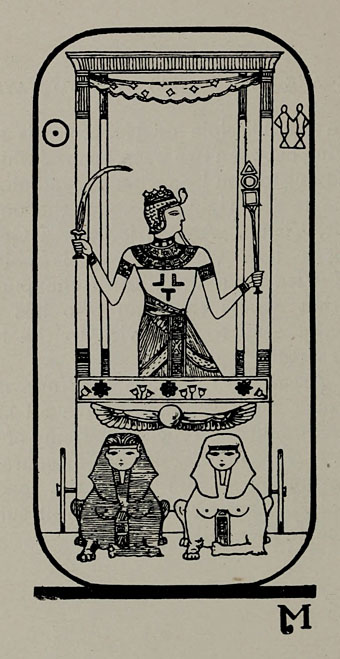

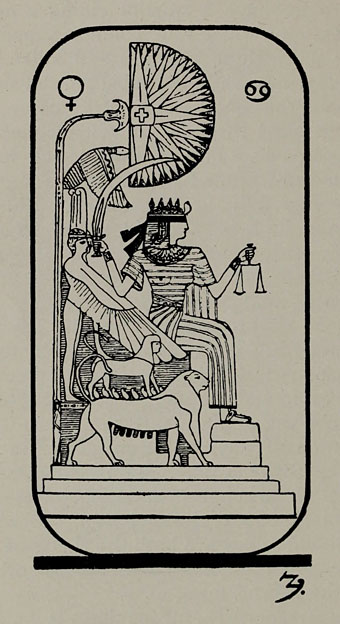

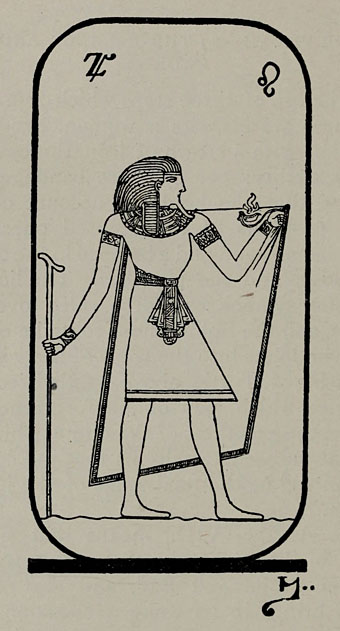

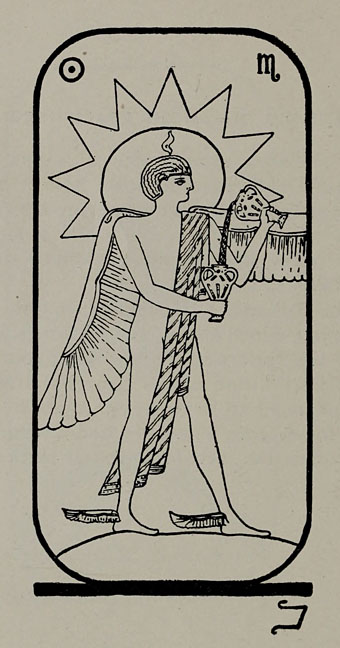

I: The Magus

While looking at Tarot designs for work purposes (again) I remembered a book I used to own that demonstrated the symbolism of the Major Arcana by using side-by-side comparisons of cards from the more well-known decks: the Tarot de Marseille, Aleister Crowley’s Thoth deck, the Rider-Waite-Smith cards, and so on. One of the decks shown wasn’t so familiar, a 19th-century design that purported to depict the Ancient Egyptian figures from which the modern Tarot is derived. Like much occult history, this is an invention but I liked the look of the cards with their simple line drawings and clever matching of Egyptian motifs with the traditional symbols. My book was borrowed years ago and never returned (the second Tarot book I’ve had this happen to; don’t lend people your Tarot books!), so I couldn’t look for a reference, but this account of the history of the so-called Egyptian Tarot supplies all the relevant details and more.

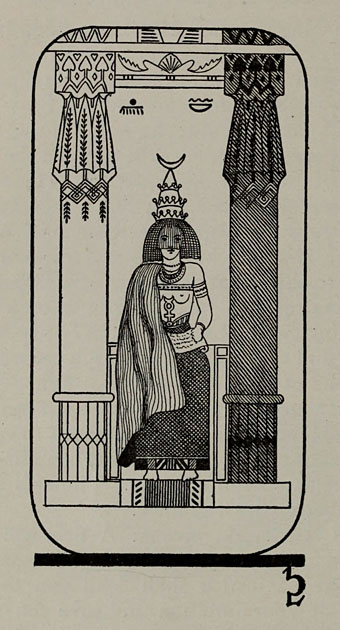

II: The Gate of the Sanctuary

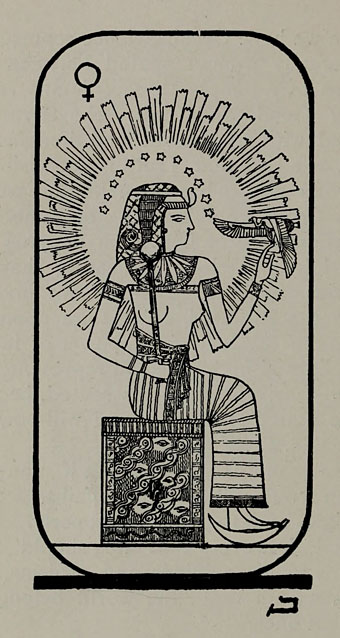

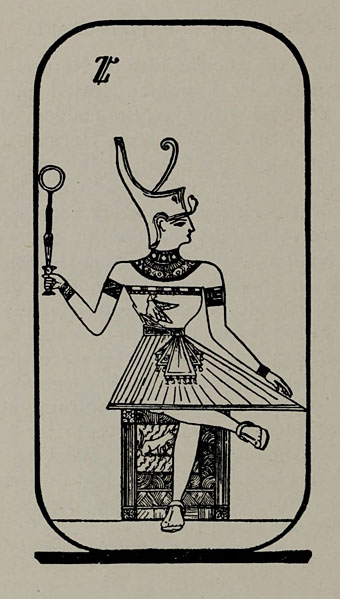

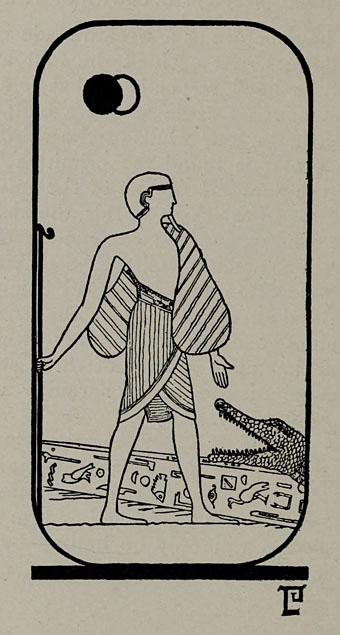

The examples shown here are from Practical Astrology (1901), a book by Edgar de Valcourt-Vermont writing under the preposterous pseudonym “Comte C. de Saint Germain” (a real person, albeit dead by 1901, with a long history of appropriation by writers and charlatans). The drawings are reworkings of the first appearance of the Egyptian designs in an earlier book, Les XXII Lames Hermètiques du Tarot Divinatoire (1896) by R. Falconnier, the drawings there being the work of one M.O. Wegener. In addition to copying the designs Valcourt-Vermont filled out the set with a Minor Arcana of his own devising that looks distinctly amateurish next to the Wegener set. Since then the cards have continued to evolve, a more recent version being the Ibis Tarot which colours the drawings in a manner that doesn’t really suit this type of art. The cards shown in my errant book were memorable in part because they stood out from their vividly-coloured counterparts.

III: Isis-Urania

It’s good to see these again, and also surprising to discover a further detail, that the Wegener drawings had been based on descriptions by Paul Christian in another occult study, Histoire de la Magie (1870). Christian’s book was the subject of a previous post for also being the source of an illustration of a witches’ sabbat that turns up all over the place, usually without credit. Not for the first time, the occult world is smaller than it seems.

IV: The Cubic Stone

Wikipedia has copies of the drawings from the Falconnier book which may also be seen at Gallica, although the copy I found there was incomplete. The Valcourt-Vermont designs were published as a complete deck, The Egyptian Tarot, by Müller in 1978.

V: Master of the Arcanes

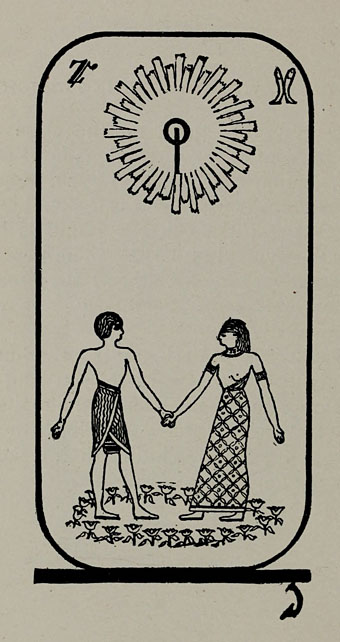

VI: The Two Ways

VII: The Chariot of Osiris

VIII: The Balance and the Sword

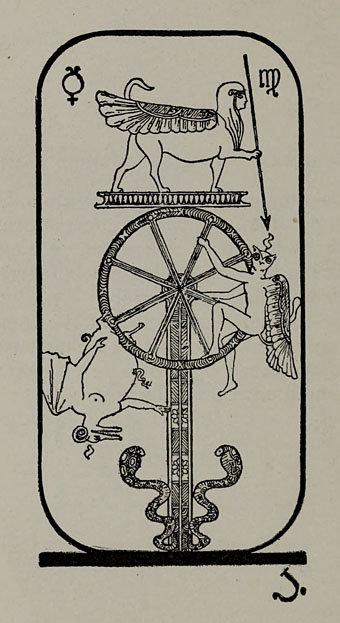

IX: The Veiled Lamp

X: The Sphinx

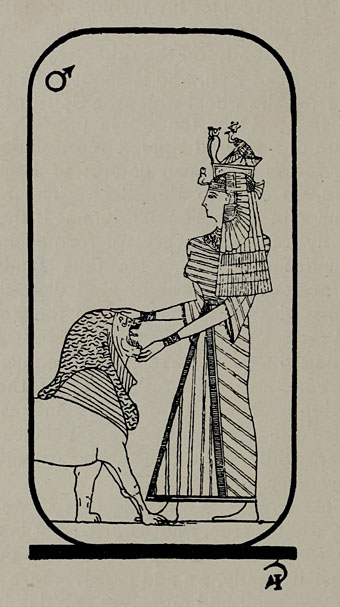

XI: The Tamed Lion

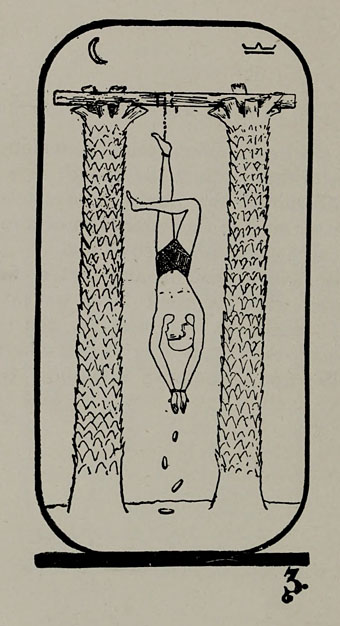

XII: The Sacrifice

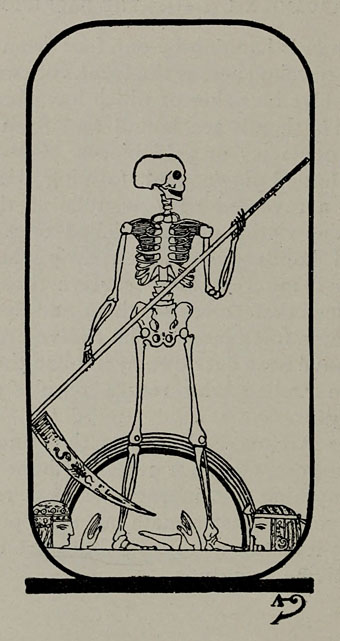

XIII: The Reaping Skeleton

XIV: The Two Urns

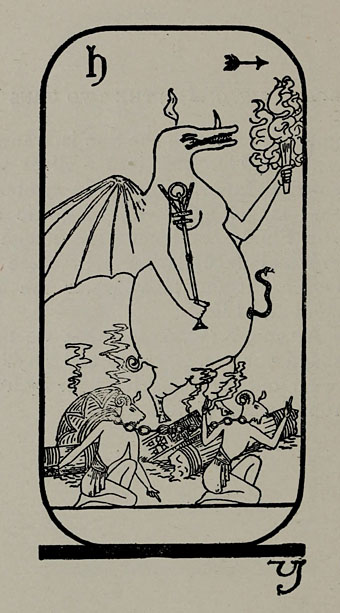

XV: Typhon

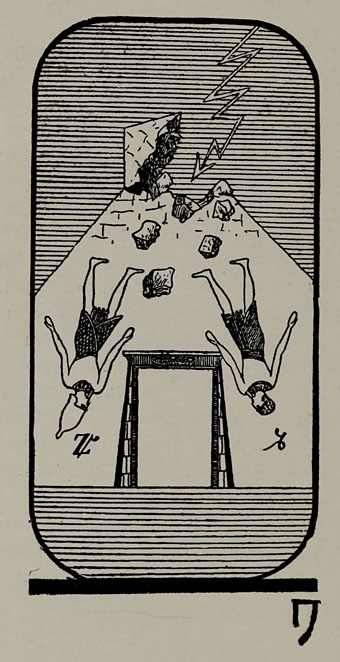

XVI: The Thunder-struck Tower

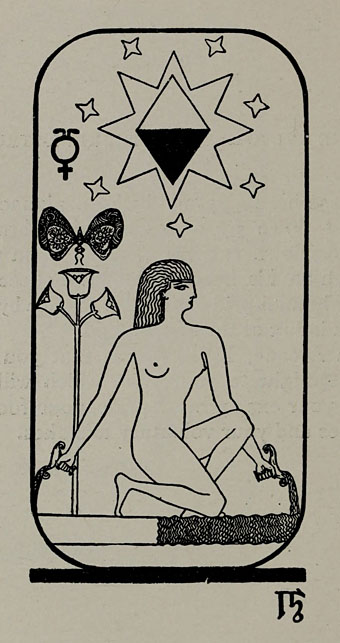

XVII: The Star of the Magi

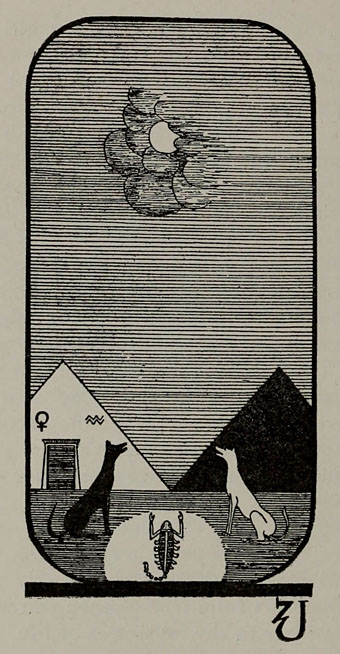

XVIII: The Twilight

XIX: The Dazzling Light

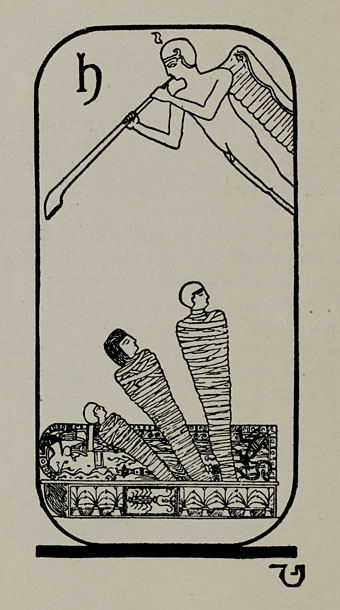

XX: The Rising of the Dead

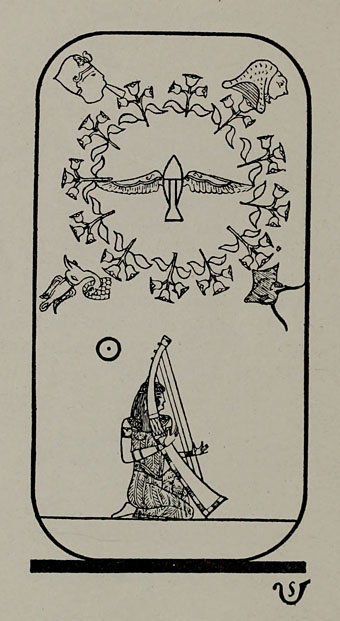

XXI: The Crown of the Magi

XXII: The Crocodile

Previously on { feuilleton }

• The Kosmische Tarot

• Alas Vegas Tarot cards

• Palladini’s Aquarian Tarot

• Le Tarot de Philippe Lemaire

• Tarotism and Fergus Hall

• Giger’s Tarot

• The Major Arcana by Jak Flash

• The art of Pamela Colman Smith, 1878–1951

• The Major Arcana

If your name is actually Edgar de Valcourt-Vermont, doesn’t that mean you were BORN with a pseudonym ?

I would generalize that to “don’t lend people your books.” Period. You will lose fewer books, for sure!

S. mcphail: It certainly sounds like one. When writing the post I nearly put “Valmont”, thinking of Les Liaisons dangereuses. Many of the French occult books of this period are pseudonymous. The “Paul Christian” mentioned above was actually Jean-Baptiste Pitois.

Howard: This is true. The books weren’t very important ones so it’s not a problem really, just notable that they both concerned the same subject.