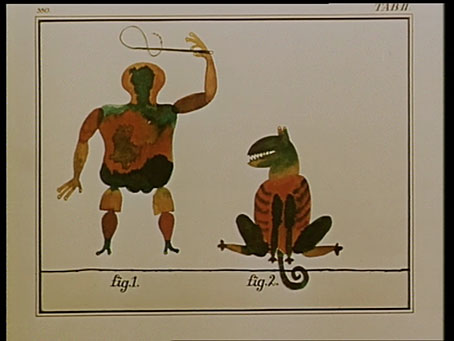

Et Cetera (1966).

A little more on the music of Czech soundtrack composer Zdeněk Liška (1922–1983). Liška seems to stand in relation to Czech cinema as Ennio Morricone does to that of the cinema of Italy, being similarly prolific, highly regarded, and idiosyncratic to a degree that makes his work immediately recognisable. Both men could also draw on their experience outside the film world to fuel their scores: Morricone for many years was a performer with Gruppo di Improvvisazione di Nuova Consonanza, a group of Italian free improvisers, while Liška’s work with electro-acoustic composition and early electronic music explains the frequent eruptions in his lush orchestrations of tape effects, exaggerated echoes and other forms of artificial processing. This kind of cross-pollination doesn’t seem so surprising today but it’s striking and surprising in soundtracks from the 1960s.

Good examples of the opposite poles of Liška can be found in two of Jan Švankmajer’s early shorts. Et Cetera (1966) is one of the director’s most formal exercises, a series of crude drawings (or cut-outs) coming to life to perform a repetitive routine before being interrupted by the words “ET CETERA”. The film plays with the audience by beginning with a title card that states “The End”, and the piece as a whole could easily be screened as an endless loop. Liška’s score is a combination of fairly minimal orchestration with a variety of electro-acoustic effects which are closer to Pierre Henry or İlhan Mimaroğlu than other Eastern European composers.

Shade of Magritte: The Flat (1968).

At the opposite end of the scale there’s the score for The Flat (1968), a typical piece of Švankmajer Surrealism with an unfortunate individual locked in a room where everything, from walls to furniture, contradicts his expectations. René Magritte casts a long shadow over this one, with director Juraj Herz making a brief appearance as a bowler-hatted man carrying a chicken. Liška’s score has a driving and reverberent choral rhythm that always makes me think of Krzysztof Komeda’s similar music for Roman Polanski’s Dance of the Vampires (1967). For such a short film it’s a remarkable piece of orchestration. The Brothers Quay are great Liška enthusiasts, and used some of the score from The Flat (and two other Liška pieces) for their 1984 film The Cabinet of Jan Švankmajer, an animated portrait of the director.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Liška’s Golem

• The Cremator by Juraj Herz