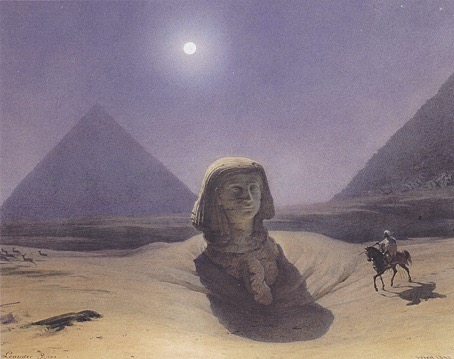

Bei den Pyramiden (1842) by Leander Russ.

A horde of sphinxes from NYPL Digital Collections and Wikimedia Commons, a pair of sites I was searching through last week. I was looking for a very particular kind of sphinx, not the Great Sphinx that sits near the Pyramids at Giza. What I wanted was something smaller and less ruined, like the sentinels that proliferated during the fads for Egyptian art and design in the early 1800s and the 1920s. My search was satisfied eventually, the results of which will be revealed in the next post.

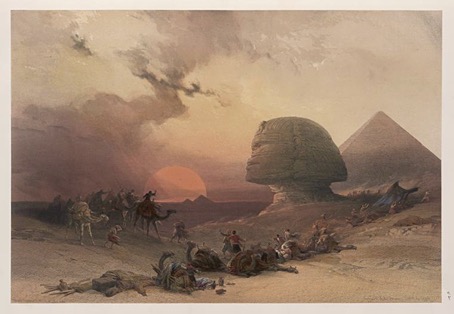

Approach of the Simoom. Desert of Gizeh (c. 1846–49) by David Roberts.

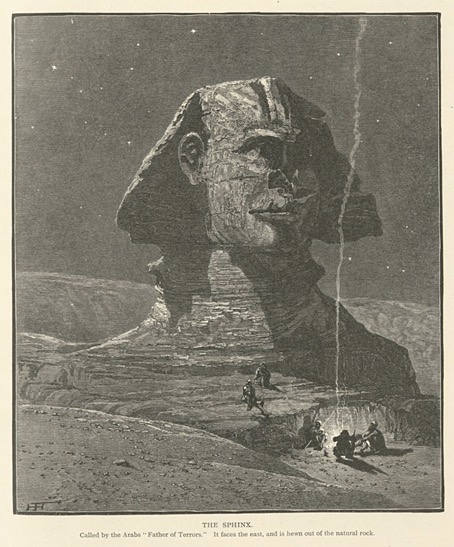

As for the Great Sphinx, I enjoy seeing artistic representations of the monument, especially those which place the creature in a dramatic setting. Older depictions tend to look bizarre or even comical, especially the ones made during the centuries when the figure was little more than a head protruding from the drifting sands. The photographs I prefer are those that show the Sphinx in the 19th century before all the restorations began, when the creature was another half-buried fragment of antiquity, not something that seems to have just been removed from a box in a museum.

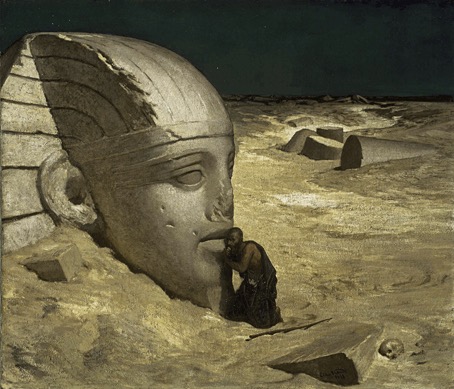

The Sphinx and Great Pyramid, Geezeh (1858–1859).

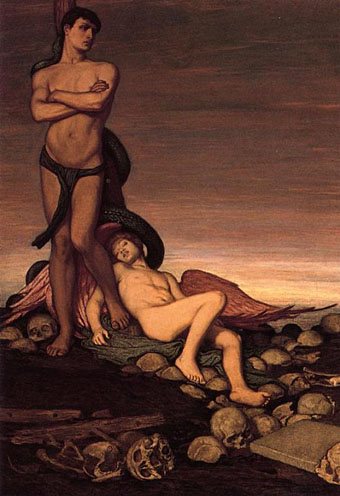

The Questioner of the Sphinx (1863) by Elihu Vedder.

The Sphinx by Harry Fenn (1881–1884). “Called by the Arabs “Father of terrors.” It faces the east, and is hewn out of the natural rock.”