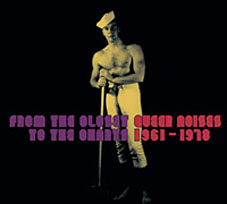

Beyond Bowie and Frankie, there’s a whole secret history of gay pop, reports Alexis Petridis

Beyond Bowie and Frankie, there’s a whole secret history of gay pop, reports Alexis Petridis

‘Wilder, madder, gayer than a Beatle’s hairdo’

It was the love that dare not sing its name—or was it? Beyond Bowie and Frankie, there’s a whole secret history of gay pop, reports Alexis Petridis

Tuesday July 4, 2006

The year 1966 is known as rock’s annus mirabilis. It was the year the right musicians found the right technology and the right drugs to catapult pop into hitherto unimagined realms of invention and sophistication: the year of the Beatles’ Revolver, the Beach Boys’ Pet Sounds and Bob Dylan’s Blonde on Blonde. But the most astonishing record of 1966 did not emanate from the unbounded imagination of Brian Wilson, or from an Abbey Road studio wreathed in pot smoke. Instead, it was the work of hapless instrumental combo the Tornados.

By 1966, the Tornados’ moment of glory—with 1962 number one Telstar—had long passed; they hadn’t had a hit in three years and every original member had departed. The single they released that year, Is That a Ship I Hear?, was their last. Tucked away on its B-side, the track Do You Come Here Often? attracted no attention, which was probably just as well. A year before the partial decriminalisation of homosexuality, the Tornados’ producer, Joe Meek, had taken it upon himself to record and release Britain’s first explicitly gay rock song, apparently undaunted by his own conviction for cottaging in 1963. (more)

Tracklist

01. Jose: At The Black Cat 02:09

02. Rod McKuen: Eros 01:42

03. Mr. Jean Fredericks: Nobody Loves A Fairy When She’s Forty 03:56

04. Byrd E. Bath & Rodney Dangerfield: Florence of Arabia 03:40

05. B.Bubba: I’d Rather Fight Than Swish 03:16

06. The Kinks: See My Friend 02:40

07. The Tornados: Do You Come Here Often? 03:53

08. The Brothers Butch: Kay, Why? 03:13

09. Teddy & Darrel: These Boots 02:22

10. Zebedy: The Man I Love 03:09

11. Curt Boettcher: Astral Cowboy 02:18

12. Harrison Kennedy: Closet Queen 03:43

13. Polly Perkins: Coochy Coo 03:19

14. Michael Cohen: Bitterfeast 03:09

15. Jobriath: I’m A Man 03:30

16. Chris Robison: Lookin’ For A Boy 03:57

17. Peter Grudzien: White Trash Hillbilly Trick 02:56

18. Valentino: I Was Born This Way 03:20

19. The Miracles: Ain’t Nobody Straight In LA 03:43

20. The Ramones: 53rd And 3rd 02:19

21. The Twinkeyz: Aliens In Our Midst 03:17

22. Dead Fingers: Talk Nobody Loves You When You’re Old And Gay 04:30

23. Black Randy & The Metro Squad: Trouble At The Cup 01:53

24. Sylvester: You Make Me Feel (Mighty Real) 03:45

Previously on { feuilleton }

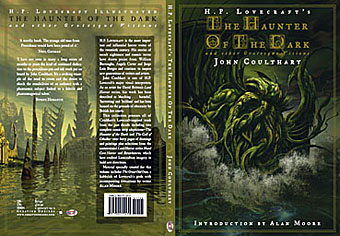

• Gay book covers