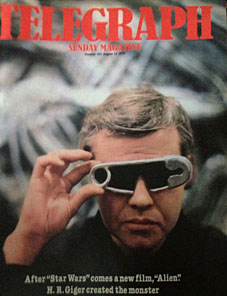

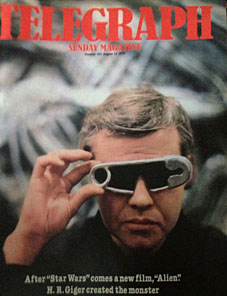

HR Giger. Photo by Eve Arnold, 1979.

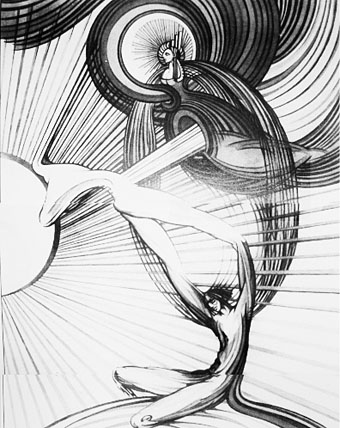

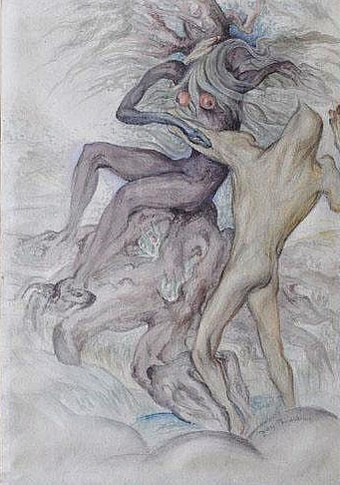

The news of HR Giger’s death was prominently featured in UK papers, something that wouldn’t have happened without his connection to the Alien films. Artists like Giger seldom make the front-page news even though he was well-established before the call from Ridley Scott. He’d already worked on Jodorowsky’s aborted Dune project alongside Moebius (who also did some work on Alien; people forget that), and his work had even appeared in a major feature film before Alien with a blink-and-you-miss-it appearance from his portrait of Li Tobler in Alain Resnais’s Providence (1977). Alien may have made him world-famous but I’ve always felt that Ridley Scott needed Giger far more than Giger needed either Scott or Hollywood. Paul Scanlon and Michael Gross’s The Book of Alien (1979) shows the production designs for the alien components before Giger’s involvement, none of which had the requisite strangeness that made the film such a success. That success would have made many artists decamp to Los Angeles in the hope of repeating the trick but Giger kept his distance. You can’t blame him when his work was diluted by James Cameron in Aliens while a unique project like Clair Noto’s The Tourist—which had heavy Giger involvement—never got made. (See here and here.)

The following is the first interview I read with Giger, a feature in the Sunday Telegraph magazine from August 1979, shortly before Alien was released in the UK. I wasn’t sure whether I still had this since I’d chopped up some of the other pages in the 1980s when I was making collages. The Sunday Telegraph then was even more of a stuffily conservative title than it is now so it’s a surprise to see Giger given such treatment; he was also the cover star although the cover on my copy is lost. I was given this by a friend whose parents read the paper; the only time I’ve ever bought the Sunday Telegraph was when I appeared in it in the early 1990s for a piece about Savoy Books. The interviewer on that occasion was Byron Rogers who I’m surprised to find wrote one of the other pieces in this magazine. (Thanks to Joe for sending me a picture of the missing cover!)

* * *

THE MAN WHO PAINTS MONSTERS IN THE NIGHT by Robin Stringer

The man in black is talking about his monster. “It is elegant, fast and terrible. It exists to destroy—and destroys to exist. Once seen it will never be forgotten. It will remain with people who have seen it, perhaps in their dreams or nightmares, for a long, long time. Perhaps for all time.”

The man in black is talking about his monster. “It is elegant, fast and terrible. It exists to destroy—and destroys to exist. Once seen it will never be forgotten. It will remain with people who have seen it, perhaps in their dreams or nightmares, for a long, long time. Perhaps for all time.”

The speaker is H. R. Giger, a Swiss-German surrealist painter, who designed the monster for Alien, the latest screen shocker, made in British studios under British direction to meet the apparently insatiable twin public cravings for space and horror films. Alien has already persuaded Americans to queue in record-breaking numbers outside their cinemas. It is said to have recouped its £15 million cost within 26 days of opening, and it comes to Britain on September 6.

The crew of a space tug on a fuelfinding mission answer a distress signal from an unknown planet. They land and discover an alien spacecraft in which, unknown to them, an awful creature has been spawned and waits seething, but with infinite patience, for a chance of life. Taken on board the space tug, clinging to one of the crew, the creature parasitically reproduces itself in him and bursts out into life in a welter of blood. It proceeds to make itself at home on board by hiding in dark places and jumping out at passers-by. It gobbles up the space crew one by one and grows prodigiously. Being unfamiliar with the monster’s lifestyle, the crew understandably panic.

That in brief the story of Alien, which, of course, has actually been spawned by the movie makers to scare us just a little bit and, in the process. to make them a lot of money.

The man who designed the monster will make some money, too—though not a lot, he says. He is not on a percentage. H. R. Giger, who calls himself H.R., because “the other things are too long and complicated”, is a chunky 39-year-old who lives with his girlfriend/secretary Mia, two cats, 12 skeletons and some books on magic in the middle of a rickety row of terraced houses in the industrial outskirts of Zurich. He always wears black.

Continue reading “The Man Who Paints Monsters In The Night”

The man in black is talking about his monster. “It is elegant, fast and terrible. It exists to destroy—and destroys to exist. Once seen it will never be forgotten. It will remain with people who have seen it, perhaps in their dreams or nightmares, for a long, long time. Perhaps for all time.”

The man in black is talking about his monster. “It is elegant, fast and terrible. It exists to destroy—and destroys to exist. Once seen it will never be forgotten. It will remain with people who have seen it, perhaps in their dreams or nightmares, for a long, long time. Perhaps for all time.”