Jean Hippolyte Flandrin (1809-1864) was a Neo-Classical painter whose work tends to lack the sensuality of his master, Ingres, yet who managed to produce one picture at least which has been an inspiration to subsequent artists and photographers.

Jeune Homme Assis au Bord de la Mer (Young Man Sitting by the Seashore) was painted in 1836. The simplicity and directness of the rendering is probably intended to be reminiscent of Classical sculpture and the figures seen on Greek pottery and bas-reliefs. There’s nothing in Flandrin’s history to suggest a homoerotic intent but the picture has that effect nonetheless, and it’s to gay artists (and viewers) that the work has mostly appealed since, as can be seen below.

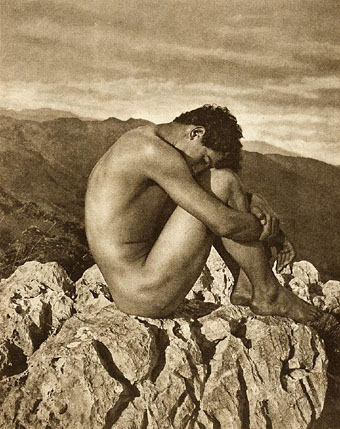

The first (?) copy, usually dated as being from 1900 although it may be earlier, and a very careful imitation of the original pose. Photographer Wilhelm von Gloeden specialised in Classical-themed gay erotica and gave his figure a Biblical allusion by titling the picture Cain. Gloeden’s follower, Gaetano d’Agata, produced his own version.

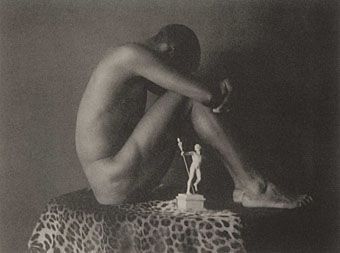

Ebony and Ivory (1897) by Fred Holland Day.

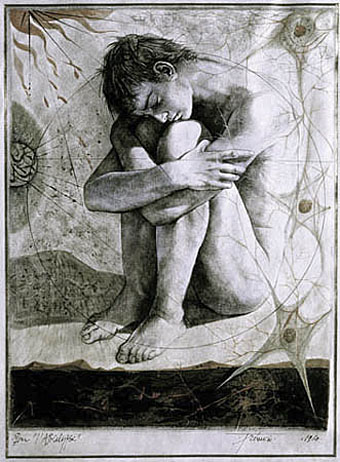

L’Apocalypse by Pierre Yves Trémois (1961).

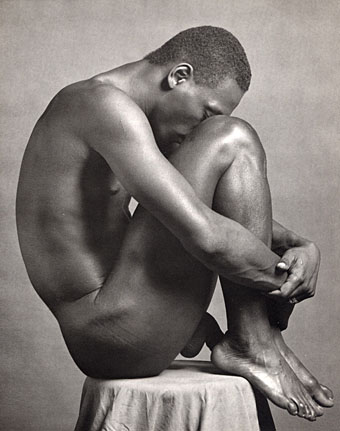

Ajitto by Robert Mapplethorpe (1981).

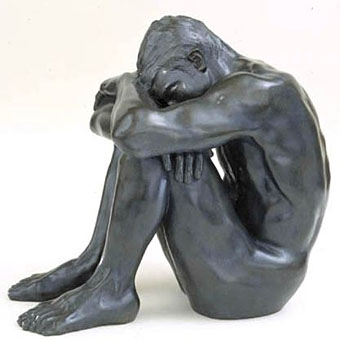

A rare sculpture version, L’Homme de l’Apocalypse by Pierre Yves Trémois (1998).

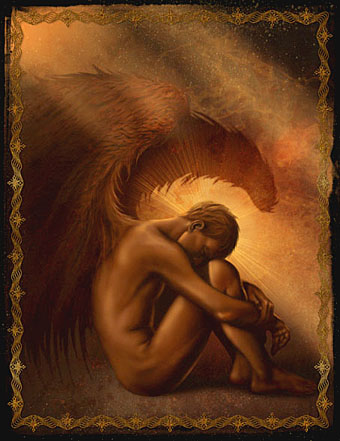

Finally, here’s my own Fallen Angel picture from 2004 which added wings to the figure.

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The recurrent pose archive

• The gay artists archive