1: The album

Back in the 1990s, when it became apparent that record companies were committed to never-ending CD reissues of their most popular albums, I suggested to a friend that this development would eventually give us releases of the unmixed recordings which the listener would then have to mix themselves: “Now you can be George Martin!” My suggestion wasn’t entirely serious, and there are many reasons why this will never happen, but the wholesale remixing of “classic” albums has been a trend now for ten years or more, and will no doubt continue. It’s easy to see endless reissues as a pernicious development—how many more copies of The Dark Side Of The Moon does the world need?—but I can think of one or two albums which would benefit from a reappraisal of their original mixes. The first two sides of Amon Düül II’s Dance Of The Lemmings, for example, have always sounded sonically inferior to the group’s other albums. The first side in particular is swamped by bass, and the drums, which are so prominent on the previous album, Yeti, are buried in the mix. Given the overtly psychedelic nature of the cover art I sometimes wonder whether anyone in the studio was drug-free during the recording.

Hawkwind shared a record label with Amon Düül II for their first six albums, and the groups are further connected by bass player Dave Anderson who played on Düül’s Yeti in 1970 and Hawkwind’s In Search Of Space in 1971. The latter has just been reissued by Cherry Red in a variety of formats which include the three-disc package (2 x CD and a blu-ray disc) that arrived here at the weekend. The set features two new mixes of the entire album (one of them being the de rigueur 5-channel surround mix), a couple of outtakes, both sides of the Silver Machine single, plus the promo film for the single. The set also contains a substantial booklet which incorporates a reprint of the 24-page logbook that came with early pressings of the album. More about that below.

Hawkwind didn’t arrive as fully-fledged cosmic voyagers on their self-titled debut in 1970, it’s here on their second album that the group myth takes flight, presenting the band as travellers through time and space, or “Sonic Assassins” as they were depicted shortly before the album’s release in Codename: “Hawkwind”, a two-page promotional comic strip created by Michael Moorcock and Jim Cawthorn. Many British bands were playing with space themes in 1971 but Hawkwind were the only group to adopt the trappings of science fiction as essential elements of their persona, elements that persisted from one album to the next. In Search Of Space is loosely spacey on the musical side—You Shouldn’t Do That is the earliest example of a future Hawkwind staple, the extended mantra-like groove over which synthesizers swoop and burble—but it’s the album package created by Barney Bubbles and (in the logbook) Robert Calvert that dispels the ambiguity of songs like Master Of The Universe and Adjust Me in a science-fiction scenario where the “space” referred to by the title is dimensional as well as cosmological, with the group’s flattened spacecraft embodied by the physical album. None of this is suggested by the music, you need to read the logbook as well, but the book and the die-cut record sleeve help to frame what would otherwise be a collection of disparate rock songs into a complex artistic statement.

When it comes to the remixing of albums I’ve been sceptical of the benefits of the trend. For the past few years Steven Wilson has been the prime remixer of music from the 1970s and 80s; among other things he remixed Hawkwind’s Warrior On The Edge Of Time and the albums on last year’s Days Of The Underground set, all of which are worth hearing. Less essential have been his new mixes for King Crimson and Tangerine Dream, the latter especially where there’s little discernible difference between the old and new versions. I think the main attraction for many listeners will be the 5-channel surround mixes, especially in the case of Tangerine Dream, but I don’t have a 5-channel sound system so can’t say how effective they are. The new In Search Of Space mixes are the work of another Steve, Stephen W. Tayler, whose reworking of the album has taken me by surprise, giving it a radically different sound rather than the discreet adjusting of levels and instrumentation that I was expecting. Dave Brock has said in interviews that he always dropped acid before making the final mix of the Hawkwind albums up to Warrior On The Edge Of Time, which may explain why In Search Of Space has always sounded rather thin and dry, while the album that followed it, Doremi Fasol Latido, is a bludgeon by comparison, with everything compressed into the wall of sound which Hawkwind had developed in their live performances. Tayler’s new mix of Master Of The Universe is revelatory, bolstering the bottom end and emphasising the inverted echoes on Nik Turner’s voice, while You Shouldn’t Do That explodes into jet-propelled life. Everything sounds more substantial, and possibly more cosmic; I’ve not done a side-by-side comparison yet but I think Tayler has given greater emphasis to the effects throughout the album, especially all the swooshing and burbling electronic instruments. If you’ve ever shared my scepticism about the remixing trend then Tayler’s work here should be considered an argument in its favour.

My own fragile copy of the original logbook. For some reason that now bewilders me I decided to colour the whole thing with watercolour paints before realising that the paper is so thin the paints were soaking through the pages.

2: The Hawkwind Log

And so to the myth. The album booklet was reprinted a few times after the album’s initial release but it remains a scarce item, in part because the first run was printed on the cheapest paper. I think this new box set is only the second non-vinyl release to include the whole thing, albeit in a compromised fashion since the reprint has been shrunk to fit the size of the booklet pages to a degree that some readers may need a magnifier to read the logbook entries. The album notes also include a reprint of the Codename: “Hawkwind” comic strip which I’m both amused and a little disgruntled to find are taken from the copies I posted here in 2008. The second page of the strip has the same dirt and creases in the corner as my online copies, blemishes that I removed when I cleaned up the strip for the book of Jim Cawthorn’s artwork that I designed in 2018. These were later included as a bonus with the special edition of Joe Banks’ Days of the Underground book. Cherry Red would have been welcome to use my print-quality copies instead of swiping them from here or wherever it was they found them.

I’ve always believed that the key to Hawkwind’s success beyond their music was the sustaining myth of the group as the crew of a spacecraft wandering (and occasionally lost) in the cosmos or, as described in the logbook, between different temporal eras. The foundation of the Hawk-myth is to be found in the logbook, and in the Space Ritual tour two years later whose concert staging was planned by Barney Bubbles, and whose Bubbles-designed tour programme was a short SF story by Robert Calvert which elaborated upon Moorcock and Cawthorn’s comic-strip scenario. All of these creations were products of the London underground scene centred around Notting Hill Gate in the late 60s and early 1970s. Moorcock, Cawthorn and presumably most of Hawkwind and their associates were living in the streets around Ladbroke Grove at the time; Frendz magazine, where the Hawkwind comic strip appeared, and where Bubbles and Calvert were sporadically employed, had its offices in Portobello Road, next door to the offices of Moorcock’s New Worlds magazine. (Stickers for Frendz are visible on the amps in the Silver Machine promo film.) Just down the road from Frendz was the Mountain Grill, the greasy-spoon café where Brock and Calvert first met, and which later gave its name to Hawkwind’s fourth studio album. The In Search Of Space logbook is very much an underground publication in the Frendz/Oz manner, especially on the pictorial side. Calvert’s text, however, is a cross between a religio-mythical tract and a scientific journal:

The spacecraft Hawkwind was found by Captain RN Calvert of the Société Astronomae (an international guild of creative artists dedicated in eternity to the discovery and demonstration of extra-terrestrial intelligence) on 8 July 1971 in the vicinity of Mare Librium near the South Pole.

The discovery of the Hawkwind has led to more wild speculation than any of the mysteries of space that we have so far encountered. The facts surrounding the discovery of this drifting two-dimensional spaceship have been so distorted by guesswork and rumour that any further attempts at assessment would only increase the density of the fog.

The following extracts from the ship’s log are presented without commentary, for the reader to form his own conclusions. They would appear to be the work of a collective robo-scribe, although one or two of the entries might possibly have been made by the hand of a single unassisted crew member whose identity still remains unknown.

We hope this amazing document will stimulate scientists, mystics, occultists, policemen and all children everywhere.

Société Astronomae

Not all of the text is Calvert’s work, many of the entries are passages borrowed or paraphrased from science books, crank books, Carlos Castanada, Black Elk Speaks, the Bible, etc, between which Calvert threads the story of the Hawkwind craft and its literal search for space:

0600 hrs. 4 July 1885. Blue pinwheel of Triangulum.

We are still in grave danger of losing our space supply unless we can get the tanks repaired and refilled soon. Travelling the two dimensional continuum of the time split it is essential to carry one’s own supply of space. Otherwise you end up flattened out like a cardboard cut-out from a cornflakes packet.

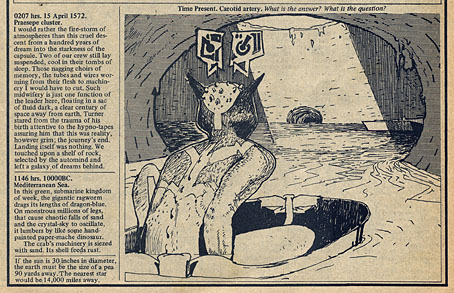

Among the other entries there’s a newspaper report from 1970 (“Court cleared at hippy flower power trial”), a Calvert take on one of Brion Gysin’s permutated poems (“Space is one trip/Trip is one space/Space is trip one…”), and a taste of the real Hawkwind future in samples of Calvert poetry/lyrics which include 10 Seconds Of Forever and The Awakening two years before Calvert’s Space Ritual readings, and a prose version of the android replica scenario that would eventually end up as Spirit Of The Age. Barney Bubbles’ graphics are a typical underground melange of borrowings from comic strips and old illustrated books together with photos of ancient monuments (Stonehenge, Glastonbury Tor), astronomical diagrams and so on. Being someone who likes to know the source of images like these I still wonder where Bubbles found illustrations like this one:

Towards the end of the logbook the predicament of the Hawkwind crew becomes severe:

1027 hrs. 5 May 1971. Ladbroke Grove.

Space/time supply indicators near to zero. Our thoughts are losing depth, soon they will fold into each other, into flatness, into nothing but surface. Our ship will fold like a cardboard file and the noises of our minds compress into a disc of shining black, spinning in eternity…

The crew survived, of course, after losing a couple of members. Dave Anderson left shortly after the recording to be replaced by Lemmy who makes his first appearance with the band in the comic strip. And drummer Terry Ollis was replaced by Simon King whose drums would power the band until the end of the decade. The next album, Doremi Fasol Latido, is full-on space-rock from start to finish, and it’s already lined up as the next remix set from Stephen Tayler. I might not have been so interested in this but hearing the changes Tayler has brought to In Search Of Space it’s starting to look irresistible.

3: An addendum with two mysteries

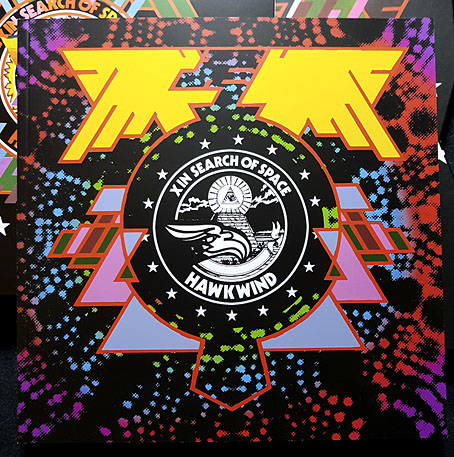

First mystery: You’d think after 53 years the title of the album under discussion wouldn’t be in question but the new reissue only adds to the confusion around this particular title. I’ve always referred to Hawkwind’s second album as In Search Of Space but the presence of an “X” at the front of the title on the cover has prompted endless debate as to whether the album is actually called X In Search Of Space or even Xin Search Of Space. X In… has some justification since Hawkwind were known as Group X in 1969 although there’s no mention of any X factor on the first album. There’s also no mention of an “X” of any kind inside the Hawklog, and yet the first ads for the album refer to Xin Search Of Space, as does the comic strip, even though the vinyl labels and the titles on the album spine have for years read In Search Of Space. If Xin Search Of Space is indeed the actual title then we have to ask who or what “Xin” is and what the phrase “Xin search of space” is supposed to mean. (According to Joe Banks Barney Bubbles said that “Xin” was correct. See his note at the end of this piece.) Cherry Red have now concurred with the nitpickers at Discogs.com that X In Search Of Space is the proper title, a decision which has caused them to open the space between the “X” and “In” on the front of the album booklet. Even so, when the menu page appears on the blu-ray disc the title still says In Search Of Space… Round and round we go, lost in time, lost in space, and meaning…

Xin or not? Make your mind up, man!

Second mystery: While I’m on the subject it’s worth throwing out another cultural conundrum that I one day hope to solve. British TV in the early 1970s used to show mid-afternoon repeats of some North American documentary series about life in the world of the future, specifically the year 2000. The programmes were all around 30 minutes long and covered things like fashion and product design as well as architecture and computer technology. I say this was a North American production because I have an idea it might have been Canadian rather than the more customary US import. It’s relevant here because each episode ended with a bunch of hippies sat outdoors playing music which I’ve always recalled sounding like some of the songs on In Search Of Space; the first time I heard the album in the late 70s the TV series came immediately to mind. The trouble is, I’ve never been able to remember what the series was called, and searches for suitable programmes about life in the future have all been in vain. (Another thing: I’m fairly sure it was on ITV not BBC after searching the BBC’s Genome archives without success.) If you have any idea what this might be then please leave a comment!

Update: Well that was quick… I’m very pleased to announce that the mystery of the futurist TV series has been solved thanks to a Twitter follower who suggested a Canadian series, Here Come the Seventies, as a likely candidate. This is indeed the series I was searching for, being broadcast in France and the UK as Towards the Year 2000. The series ran from 1970 to 1972, and featured music by Canadian prog-band Syrinx who provided the Moog-heavy theme tune while also appearing at the end of each episode playing on an island in a river or lake (see this clip). The title theme sounds nothing like Hawkwind, it was the end version I was reminded of when listening to In Search Of Space, mainly because of the combination of sax and synth. Hearing it again it doesn’t sound like Hawkwind either but that’s okay, I’m happy that this nagging question has been laid to rest.

• Wikipedia link | IMDB link | Opening titles

Previously on { feuilleton }

• New Wave Strangeness: Hawkwind’s Calvert years

• Twinkle, twinkle little stars

• Motorway cities

• Reality you can rely on

• Silver machines

• Notes from the Underground

• Hawkwind: Days of the Underground

• The Chronicle of the Cursed Sleeve

• Rock shirts

• The Cosmic Grill

• Void City

• Hawk things

• The Sonic Assassins

• Barney Bubbles: artist and designer

I’ve a vague memory of Eno re-issuing an older track online that would allow fans to remix it. Also, I’ve pushed friends in a few semi-notable bands to try this, but it’s always hit a wall with the record companies for whatever reason. It just seems that, since computers and internet, this should be a common feature for bands to capitalize on in the sake of, at least, community building.

Hi Ron,

Some of the tracks from Eno & Byrne’s My Life In The Bush Of Ghosts were made available for remixing when the album was reissued in 2006, that’s the only Eno-related example I know of. The raw tracks are no longer accessible but some of the variable results may be heard at the Internet Archive. Copyright issues were avoided somewhat by releasing the recordings under a Creative Commons licence.

Hi John, regarding the source of the images for the Hawkwind Log, I remember recognising the ‘Skeleton !’ ‘Thine alabaster towns will tumble etc’ picture as a clipping from a Fireball XL5 comic strip. I was eight or nine when I bought the comic and then a few years later, In Search of Space was one of the albums that got me into Hawkwind. You are right about the mythology the band created being effective – I certainly bought into it, maybe a bit too much.

As for the ‘Skeleton !’ image, it was drawn by Frank Hampson, the Dan Dare guy, and appeared first in colour in TV 21. There’s an image on the internet which is dated ‘2065’ and I seem to remember TV21 treated the Gerry Anderson TV shows, all set 100 years in the future, as if they were real, so I guess it must have been 1965 in our space-time continuum. I think the Countdown comic reprinted some of the old strips a few years later, in black and white, alongside newer material.

Good luck with sourcing some of the other images.

All the best,

Nick

Thanks, Nick. It doesn’t surprise me that Gerry Anderson is one of the image sources, it’s not like there was a lot of choice at the time.

I think the “As Above, So Below” drawing is from Herbert Granville Fell’s illustrated edition of The Book of Job. Fell was an exceptional illustrator during the 1890s but I’ve yet to find any of his books in complete online editions. I had a link for the Hawklog drawing but don’t have it to hand just now.