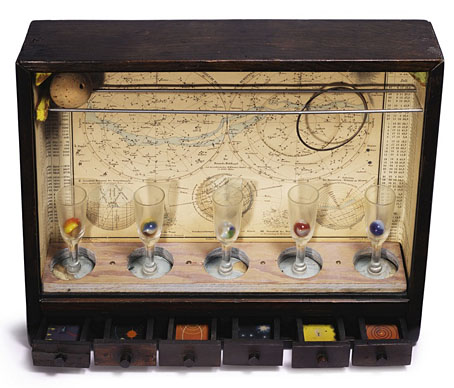

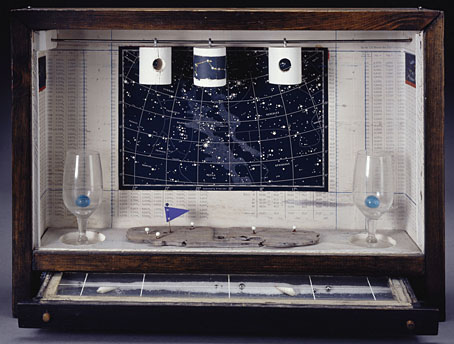

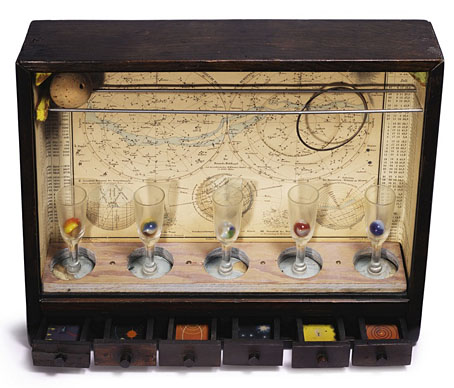

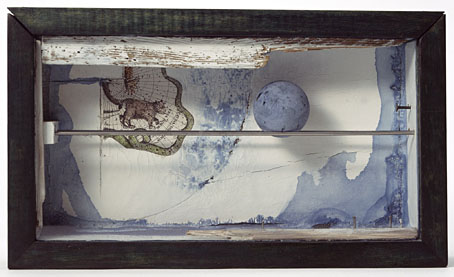

Untitled (Die Sternen-Welt), c.1950.

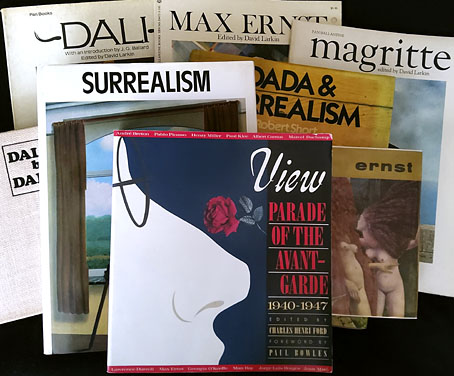

Among my current reading is Utopia Parkway (1997), Deborah Solomon’s biography of American artist Joseph Cornell (1903–1972). The book is very good for the factual data but I’ve been less enamoured by Solomon’s attempts to dredge biographical significance from Cornell’s hermetic and allusive work, or by her dismissive comments about other artists. Her account is most valuable when showing the evolution of Cornell’s art, the way he developed his often erratic and hesitant working methods. Most of Cornell’s works that I’ve seen in the past have been solitary examples, usually in books about Surrealism, so I wasn’t aware that so many of his celebrated and influential box assemblages were produced as themed series: Aviaries, Dovecotes, Hotels, and so on.

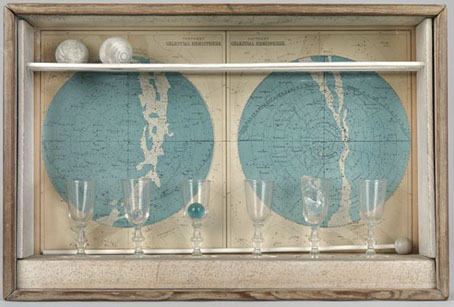

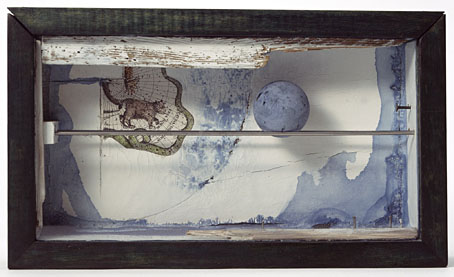

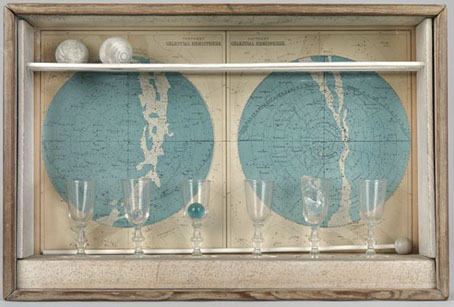

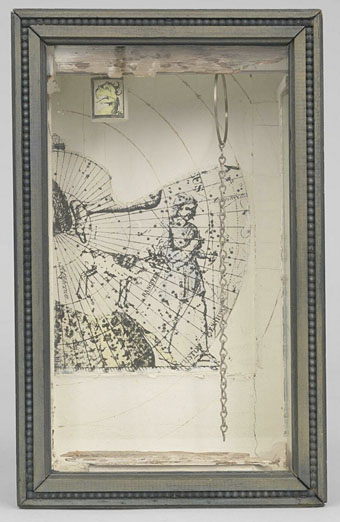

Planet Set, Tête Etoilée, Giuditta Pasta (dédicace), 1950.

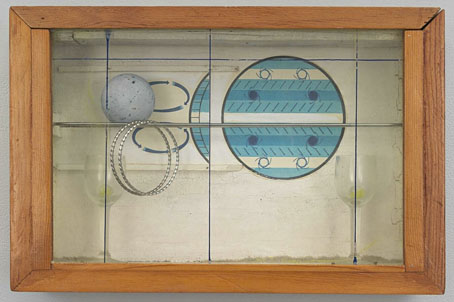

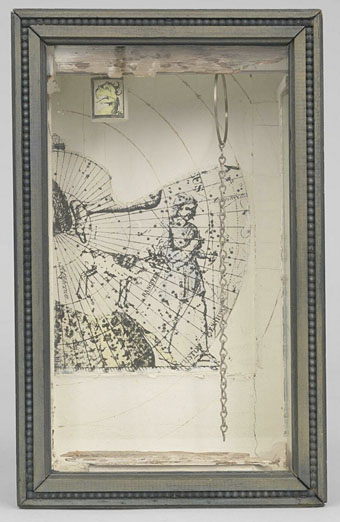

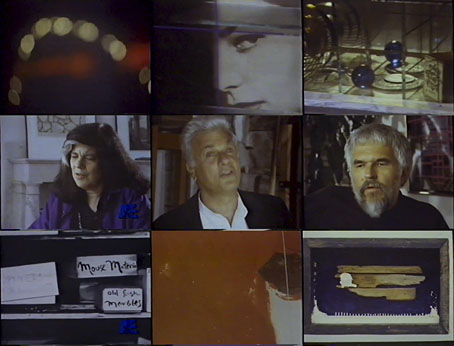

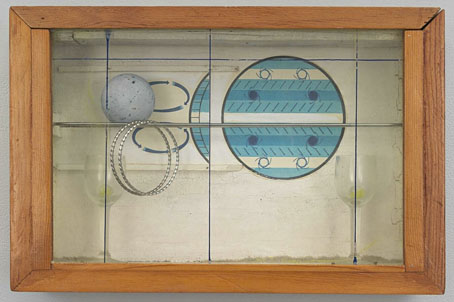

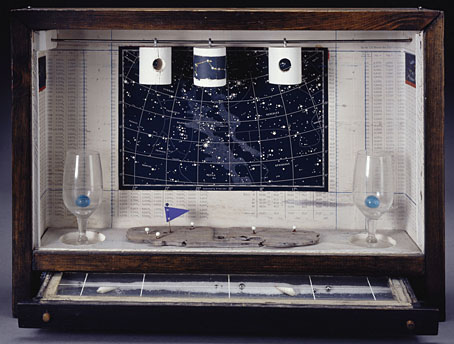

Astronomy was a Cornell passion which also provided the subject for another themed series, Observatories, a collection of boxes begun later in his career for which star maps and heavenly bodies were the dominant concern. By the 1950s his creations were much more refined than some of his earlier constructions, although the box contents include many familiar Cornell ingredients: antique maps and diagrams, glassware, spherical objects, etc. The examples here are a small selection of those to be found scattered around various websites. Another consequence of reading Solomon’s book is realising that I could do with a companion volume filled with Cornell’s artwork. There doesn’t seem to be a decent monograph as yet; if anyone has any suggestions (preferably with colour plates) then please leave a comment.

Sun Box (1950). [Not a constellation, obviously, but from the same astronomical series.]

Untitled (Celestial Navigation), 1956–58.

Celestial Navigation (c.1958).

Untitled (Canis Major Constellation), c.1960.

Custodian—M.M. (1962).

Previously on { feuilleton }

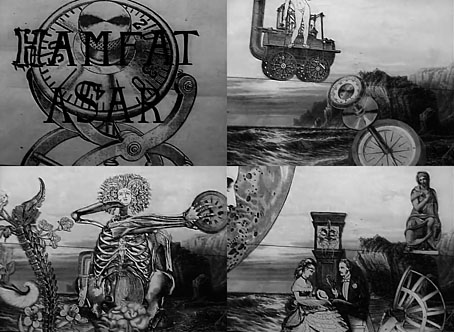

• Joseph Cornell: Worlds in a Box

• Joseph Cornell, 1967

• Rose Hobart by Joseph Cornell

• View: The Modern Magazine