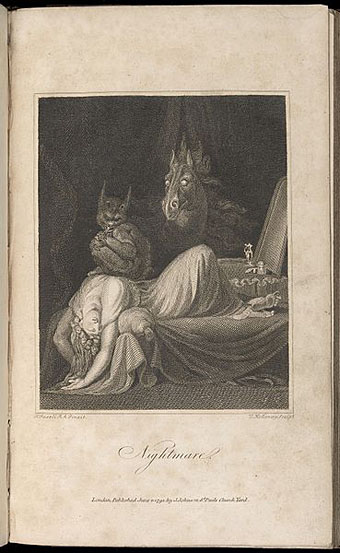

The Nightmare (1781).

Christopher Frayling’s Nightmare: The Birth of Horror (1996) opens with a prologue examining Henry Fuseli’s most celebrated painting:

Henry Fuseli, who later wrote that “one of the most unexplored regions of art are dreams”, and who was said to have supped on raw pork chops specifically to induce his nightmare, made his name with this painting. And engraved versions, produced in 1782, 1783 and 1784, distributed the image across Europe, until Fuseli’s masterpiece became the way of visualising bad dreams.

Although The Nightmare was painted just before the Romantic craze in Western Europe—which revelled in peeling back the veneer of rational civilisation to reveal the “natural” being or the raw sensations beneath, sometimes through the gateway of dreams—it was well-known to the writers and painters of the early nineteenth century. One of them wrote that “it was Fuseli who made real and visible to us the vague and insubstantial phantoms which haunt like dim dreams the oppressed imagination”.

The Nightmare was fascinating—and scary—because it operated at so many different levels at once. It was set in the present (the stool and bedside table are “contemporary” in style), and it was concerned not so much with an individual’s nightmare—the usual subject-matter of dream paintings, often involving famous individuals and their prophecies—as with nightmares in general. It was not A Nightmare, but The Nightmare; not a vision but a sensation. This gave it a direct impact, unmediated by history, which put a lot of critics off.

The Nightmare (1791).

Later generations of critics have had no such problems, of course, nor have the legions of artists and cartoonists who’ve plagiarised and parodied this memorable scene. I had a vague notion of collecting some of the derivations but a quick image search reveals an endless profusion of squatting figures and thrusting horse heads. Wikipedia did provide two of the engraved versions, however. Of the two paintings above I’ve always preferred the later one: the incubus, or “mara” as Frayling calls it, looks more sinister, and the horse head has become an almost unavoidable sexual symbol. No wonder that Siegmund Freud had a copy of The Nightmare on the wall of his waiting room.

Engraving by Thomas Burke (1783).

Frontispiece from The Poetical Works of Erasmus Darwin (1806).

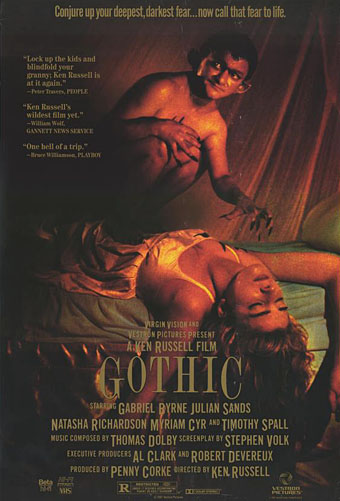

Gothic (1986): Kiran Shah and Natasha Richardson.

Frayling’s book connects Fuseli’s painting to Frankenstein, and Ken Russell did the same in Gothic, a typically exuberant dramatisation of the events at the Villa Diodati in 1816 that led to the creation of Mary Shelley’s novel. This scene was also used for the poster art, something I’d forgotten about. There’s an earlier quotation in Penda’s Fen (1974) but I’ll not spoil that moment by posting a screenshot.

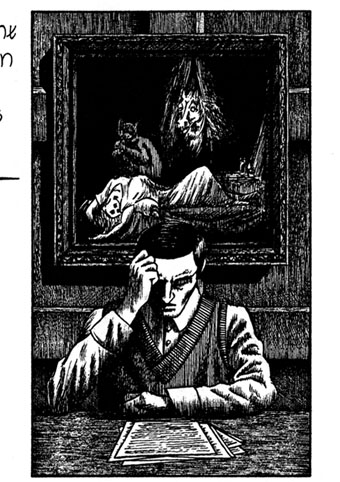

And it would be remiss of me to not mention two quotations of my own…

HP Lovecraft praises Fuseli in at least two of his stories so I put The Nightmare into my adaptation of The Call of Cthulhu in 1988. Not a very good rendering when placed near the original.

Equus (1997).

And in 1997 I was doing a lot of painting both commercially and as personal work. This was an example of the latter, a Baconesque treatment of the horse from the 1791 picture.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Nightmare: The Birth of Horror

• Intertextuality

• Dark horses

• HP Lovecraft’s favourite artists

a quick image search reveals an endless profusion of squatting figures and thrusting horse heads

I was collecting versions for a while with the idea of assembling them into an animated GIF.

Cradle of Filth paid an interesting homage to Fuseli’s Nightmare on the part of booklet artwork for Thornography : http://s.pixogs.com/image/R-5351379-1391249890-1520.jpeg

So glad you included Russell’s Gothic!

I wonder if Kafka was influenced by Fuseli’s ‘Nightmare’ in his story,’A Country Doctor’… the horses who thrust their heads in through the window… it seems that Yamamura who made an animated film of the story (see YouTube) was influenced, because his horses share the same white glowing eyes.

Crumb’s version

http://media-cache-ec0.pinimg.com/736x/e6/ba/e3/e6bae3a56f7923a7fa06412190374d15.jpg

Not Fuseli, but it does combine the two elements of “horse” and “fear”:

http://i945.photobucket.com/albums/ad292/smutclyde/horseamplion.gif

Andy: Thanks, that’s one I’d not seen (it’s after my time with the band), and a good example of the endless variety of the image.

Paul: No idea about the Kafka influence but according to Frayling the strange eyes derive from a Greek statue that Fuseli used as a model.

Gabriel: I’d not seen that one before but Crumb did an earlier version in one of his Snoid strips.

herr doktor bimler: I don’t think I’d realised before how similar those horses are. I’ve seen at least one of those in Tate Britain.

I’ve seen at least one of those in Tate Britain.

There is one in the Liverpool gallery too, which I was looking at when I realised how many different versions there are.