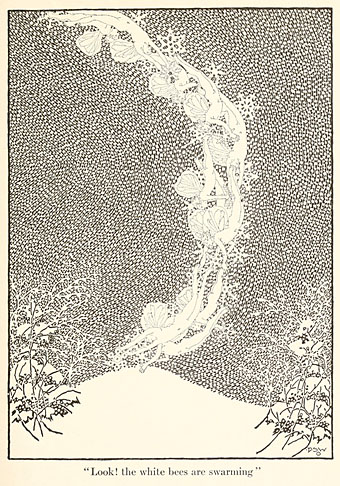

Edmund Dulac.

Empty, vast, and cold were the halls of the Snow Queen. The flickering flame of the northern lights could be plainly seen, whether they rose high or low in the heavens, from every part of the castle. In the midst of its empty, endless hall of snow was a frozen lake, broken on its surface into a thousand forms; each piece resembled another, from being in itself perfect as a work of art, and in the centre of this lake sat the Snow Queen, when she was at home. She called the lake “The Mirror of Reason,” and said that it was the best, and indeed the only one in the world.

Here in Britain it may not be quite as cold as it was earlier in the month but the Snow Queen still has us in her thrall. Hans Christian Andersen’s fairy tale was published in 1845 and, like many of the writer’s stories, is a blend of the beguiling and irritating: beguiling for the traces of older folk tales in its trolls, their magic mirror, and the Snow Queen as an embodiment of the season; irritating for the Christian gloss which is layered over everything like a sugar-coating. In this respect it’s a lot like Christmas; religiose sentimentality papered over winter rituals that are older and darker than the celebrations we’re supposed to acknowledge.

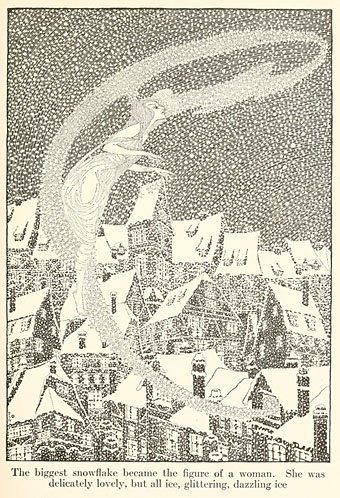

Edmund Dulac.

Andersen’s story has been illustrated and filmed many times with varying success. The Internet Archive has several illustrated editions, the selections here being from two of the better ones. Edmund Dulac’s Stories from Hans Andersen (1911) is one of the shorter collections and features predominantly colour pictures while Dugald Stewart Walker’s Fairy Tales from Hans Christian Andersen (1914) is one of the most heavily illustrated as well as having finer renderings of many stories. But not of the Snow Queen in her palace, Dulac beats everyone there.

Dugald Stewart Walker.

This description stood out from the second part of Andersen’s tale:

In winter all this pleasure came to an end, for the windows were sometimes quite frozen over. But then they would warm copper pennies on the stove, and hold the warm pennies against the frozen pane; there would be very soon a little round hole through which they could peep…

My sister and I had been reminiscing recently about growing up in the 1960s when central heating and double-glazing were a lot less common than they are today. This meant little or no heating in bedrooms, so very cold weather often meant the same frozen windows which Andersen describes. People in rural places will be familiar with this but it’s something I haven’t seen for years. When you’re a child it’s quite an excitement waking up to find that Jack Frost has paid a visit but these days I prefer a warm house.

As usual I’ll be away for a few days so the archive feature will be activated to summon posts from the past. Have a good one. And Gruß vom Krampus!

Dugald Stewart Walker.

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The illustrators archive

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Dugald Stewart Walker revisited

• More Arabian Nights

• The art of Dugald Stewart Walker, 1883–1937