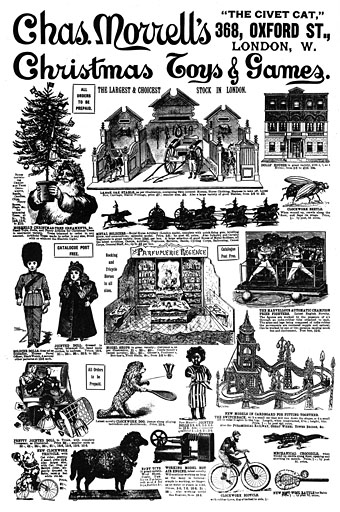

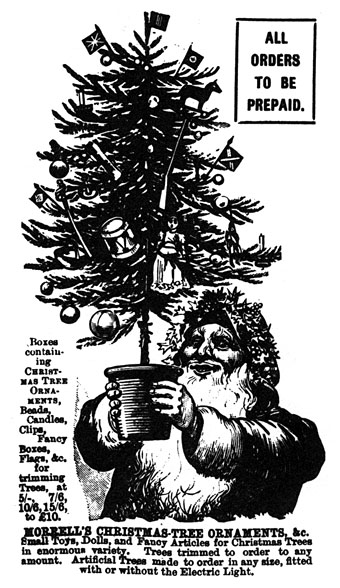

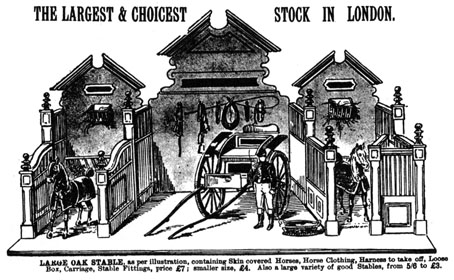

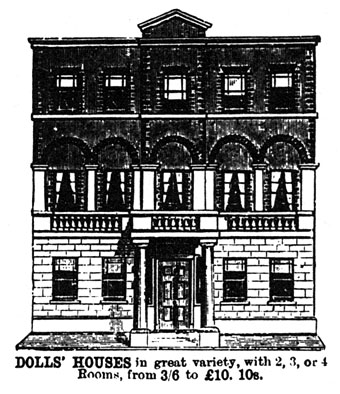

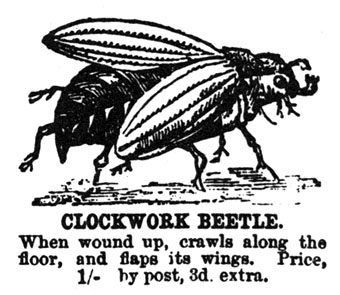

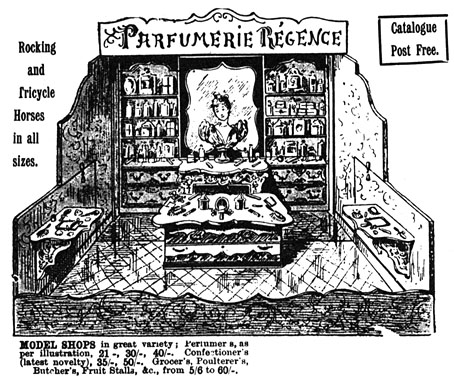

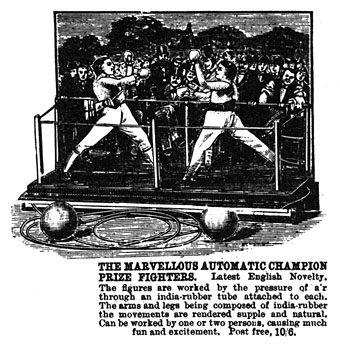

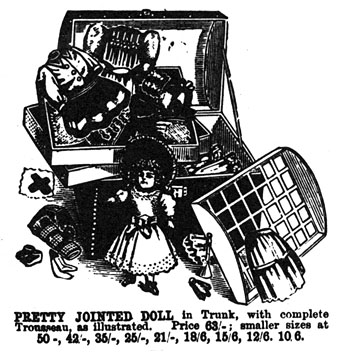

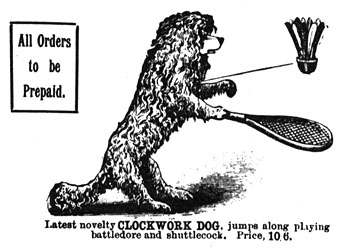

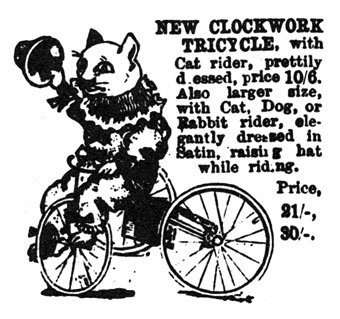

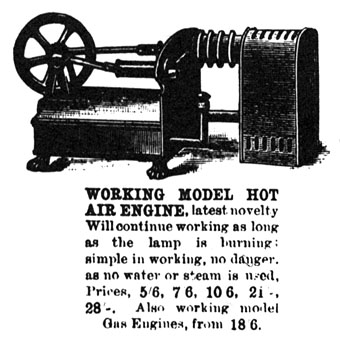

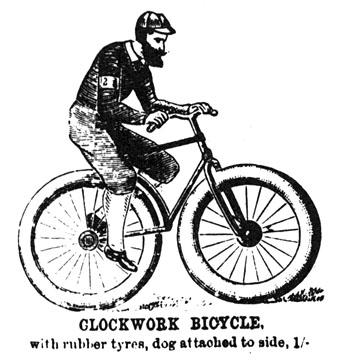

An ad from The Queen magazine, November 28th, 1896, showing what lucky children in London and elsewhere might expect to receive for Christmas. (Close-ups follow below.) Those children would have needed wealthy parents since many of these toys cost half a week’s pay or more for the average worker. Scanned from Victorian Advertisements (1968) by Leonard de Vries.

A note about the prices: 10/6 means “ten and six” or 10 shillings (10s) and sixpence (6d). Before decimalisation in 1971 there were 12 pence to the shilling and 20 shillings to the pound. 1 shilling is the equivalent of 5 pence in today’s currency.

I think I want that perfumerie…

I wonder how detailed those shops were? They’re certainly expensive so I’d guess there was a lot of workmanship involved, lots of tiny pieces for a child to lose or swallow!

I like the switchback although it’s only cardboard so probably looks better as a drawing.

Fascinating post, John. One can only wonder at the state of the ‘Commoner quality’ New Mulatto dolls – or even what the Old Mulatto Dolls looked like.

I love the typically diverse 19th century spelling: A RATTLE for Babie.

I suppose a commoner doll may have lacked joints or had less lead paint or something.

I was struck by the list of model shops, most of which can still be found in today’s high streets despite the best efforts of Sainsbury’s, Tesco and co. Yet I don’t recall ever having seen a poulterer anywhere.

I’m also fascinated by the mulatto dolls. Was there some sort of Caribbean culture craze in 1896? Was a mulatto doll somehow safer to play with than a simply black one?

I’d imagine the doll was part of the general trend for black dolls, golliwogs, etc and may well have been misnamed here, sensitivity and accuracy not being a major concern. Florence Kate Upton’s Adventures of Two Dutch Dolls and A Golliwogg was published the year before and Helen Bannerman’s Little Black Sambo three years later. The latter concerns a black boy having adventures in a very unrealistic India. The British Empire was at its height in 1896 and anyone with dark skin was seen as part of an undifferentiated mass regardless of origin.

James: A friend informs me that mulatto dolls would be easier to make since you could take a white doll and paint it brown. No need to alter the features that way, you’d get two dolls out of the one mould. Makes sense when you think about it.

Hi John, this is a great article. I like how it is that these toys were so much wanted in the 1800s but seem so exotic for today. Great blow-up pictures by the way. I can see the details so much clearer.