The riddle of the rocks by Jonathan Jones

It was the art movement that shocked the world. It was sexy, weird and dangerous—and it’s still hugely influential today. Jonathan Jones travels to the coast of Spain to explore the landscape that inspired Salvador Dalí, the greatest surrealist of them all.

The Guardian, Monday March 5, 2007

I AM SCRAMBLING over the rocks that dominate the coastline of Cadaqués in north-east Spain. They look like crumbling chunks of bread floating on a soup of seawater. Surreal is a word we throw about easily today, almost a century after it was coined by the poet Guillaume Apollinaire. Yet if there is anywhere on earth you can still hope to put a precise and historical meaning on the “surreal” and “surrealism”, it is among these rocks. To scramble over them is to enter a world of distorted scale inhabited by tiny monsters. Armoured invertebrates crawl about on barely submerged formations. I reach into the water for a shell and the orange pincers of a hermit crab flick my fingers away.

The entire history of surrealism—from the collages of Max Ernst to Salvador Dalí’s Lobster Telephone—can be read in these igneous formations, just as surely as they unfold the geological history of Catalonia.

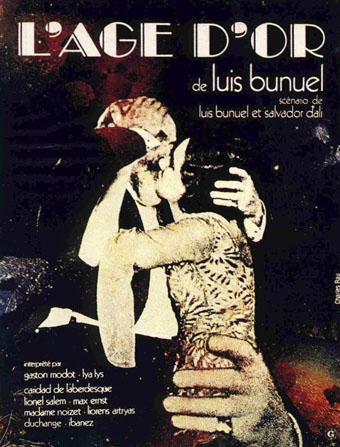

I sit down on a jagged ridge. What if I fell? Would they find a skeleton looking just like the bones of the four dead bishops in L’Age d’Or, the surrealist film Luis Buñuel shot here in 1930?

Buñuel had been shown these rocks by his college friend Dalí years earlier. It was here they had scripted their infamous film Un Chien Andalou. Dalí came from Figueras, on the Ampurdán plain beyond the mountains that enclose Cadaqués, and spent his childhood summers here, exploring the rock pools and being cruel to the sea creatures. In most people’s eyes, this is a beautiful Mediterranean setting. It certainly looked lovely to Dalí’s close friend, the poet Federico García Lorca, when Dalí brought him here in the 1920s: in his Ode to Salvador Dalí, Lorca lyrically praises the moon reflected in the calm, wide bay…

Continues here.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• The persistence of DNA

• Salvador Dalí’s apocalyptic happening

• The music of Igor Wakhévitch

• Dalí Atomicus

• Las Pozas and Edward James

• Impressions de la Haute Mongolie

Its interesting how many meanings the word ‘surrealism’ has to so many people. I’ve never seen L’Age d’Or myself. Maybe that film would sway my opinion, but I definitely think in terms of cinema, the best one classified as surrealist was Cocteau.

“Surreal” is one of those terms like “psychedelic” that began with a far narrower definition than it has now. So it used to be solely about introducing the irrational or the unconscious into art whereas now something a slightly quirky TV ad gets called surreal.

Cocteau knew the Surrealists and borrowed from their philosophy, but he was also borrowing from Greek myths, Symbolism, Picasso and anything else that informed his own private mythology. It’s that private mythology that sets him slightly apart, I think. Also André Breton was something of a homophobe (if I remember correctly) so I doubt they would have got on.

L’Age D’Or is well worth seeing, as are Buñuel’s other films. Even his later works have Surrealist qualities. You can see Un Chien Andalou at ubu.com via the link near the top of this post.

I’ve seen other Brunel pics before so I am kind of surprised I’d never seen D’Or before. I hear people calling Cocteau surreal all the time, (not that a lot of people on the street know the name) which works alright nowadays. I like some other artists ‘considered’ to be part of the movement, but don’t know much of the movement itself. The fact in going by how they thought that Dali could no longer be surrealist because of an interest with Nazis or perhaps just Hitler, makes me less interested in the subculture

I used to think it was just a useful word and never a trend. If Breton was actually homophobic, I find that somewhat funny, but then again, after watchin La Belle et Le Bete (my computer won’t let me punctuate) I immediately caught a Cocteau fever and looked up a bunch of random shit up on him, and I admit I find his writing asinine, and was surprised to later hear he was gay. His writing struck me as that of a tight-assed, monarchial type.

That was not intended as a bad pun by the way.

Breton was a hardcore Communist, as were many intellectuals of that period, although much of the impulses of Surrealism came from anarchist sources and people like Lautréamont and Alfred Jarry who were “surreal” before the term was invented. The Soviets would have condemned Surrealism just as they eventually condemned every art movement that wasn’t tedious Socialist Realism. This probably explains why Breton was expelled from the Communist Party!

The movement, such as it was, was a mass of contrary impulses fighting each other: Buñuel was anti-Catholic, so was Max Ernst; some were Communists, others anarchists, Dalí was a monarchist (!), etc. The movement didn’t last because they kept fighting and arguing, then the war came and scattered everyone. Dalí was too big an ego to be confined to a group, and it’s debatable how much of his behaviour was intended to get him expelled anyway. Breton needed Dalí’s talent more than Dalí needed Breton.

Breton’s Manifestos are worth a look to see what he was thinking:

http://www.opusforfour.com/breton.html#manifesto

I’ve never been interested in Cocteau’s writing either, it’s his films and his art I like.

To be honest, the only thing I’d ever read of Breton’s was his his black humor anthology, none of which was really his innovation, so it really shouldn’t surprise me that I didn’t know he was Communist either. Les Chants de Maldoror is another piece that, in an ideally freaked out world, I would have had Harry Clarke illustrate. I’ve read nothing of Alfred Jarry, though it all sounds interesting.

It doesn’t surprise me Brunel being anti-Catholic, I try not to draw too many lines though. I have an innate gag reflex ‘Christianity’ period, I’d actually rather be around Catholics though, because, well at least on this side of the pond, Catholics tend to celebrate their events by getting drunk rather than eating too much. So whenever Easter or any holiday hits where people try and make you feel ashamed spending it alone, even if you resent it, one can be sure who I’ll be with.

Back to the point though, yes I agree, Dali belongs to no one. I guess I understand monarchist viewpoints, as long as they’re based on character rather than bloodline. He gets called a thousand different things, and he could do just about anything. He seemed to be one of those guys who could have strayed out into the mainstream view without being at all watered down by it. A Hollywood (I guess not anymore) equivelant might be Roman Polanski. He liked books like the Tenent and El Club Dumas enough to adapt them. His tastes seem offbeat enough, how great it would be if he adapted one of Dedalus’s better novels. I’ll have to check that Breton link.