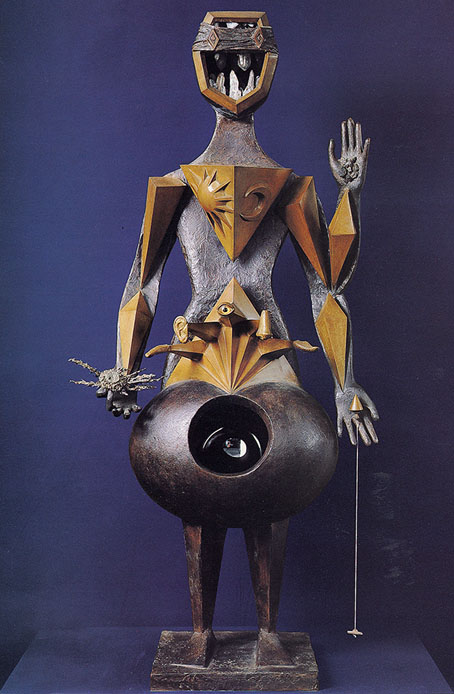

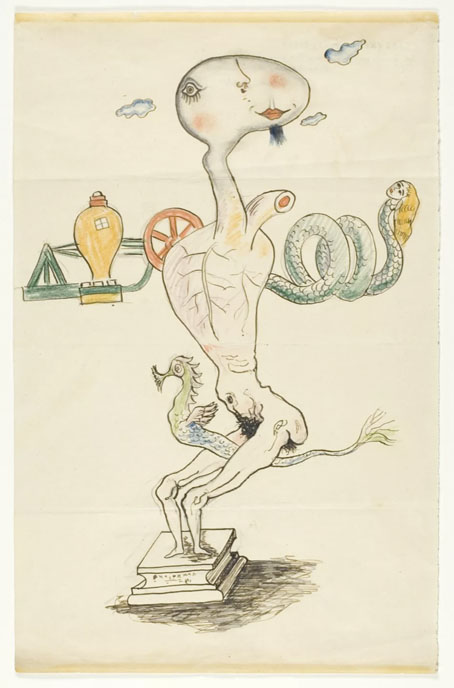

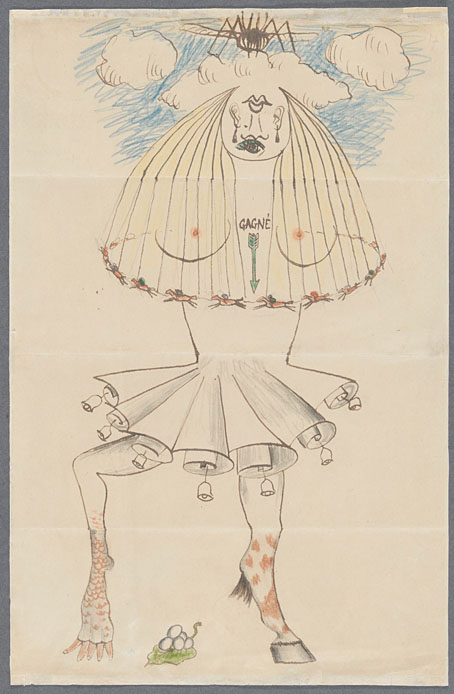

From One Dough (1996) by Martin Stejskal, Jan Svankmajer, Eva Svankmajerová.

From A Dictionary of Surrealism by José Pierre (Eyre Methuen, 1974):

Exquisite corpse. The most famous of the surrealist games takes its name from the opening sentence that materialized: “Le cadavre—exquis—boira—le vin—nouveau” (1925) (The exquisite corpse—will drink—the new wine). It was produced by five players writing in turn subject, adjective, verb, object, complement, each folding over the paper so that the next player could not see what had been already written. The violent whiff of strangeness and the droll effects obtained by these verbal collages reappeared in the drawn “exquisite corpses” in which Surrealist poets and painters often combined. Despite the fact that each contribution—especially in the case of painters—is relatively identifiable, the total effect (mostly in the form of a “personage”) results from the combined elements. In this, the “exquisite corpse” can claim to have scored a victory for collective invention over individual invention and over the “signature”.

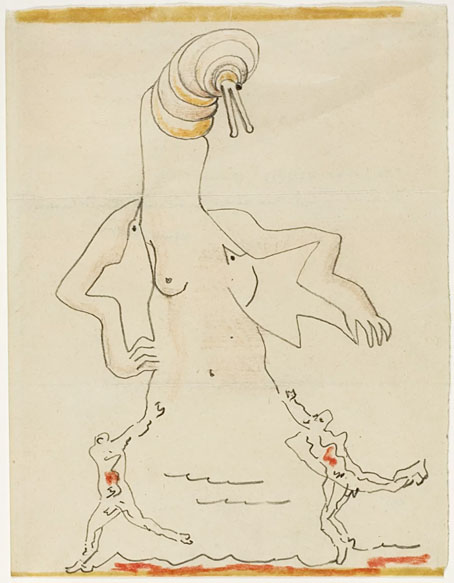

Nude (1926–27) by Yves Tanguy, Joan Miró, Max Morise, Man Ray.

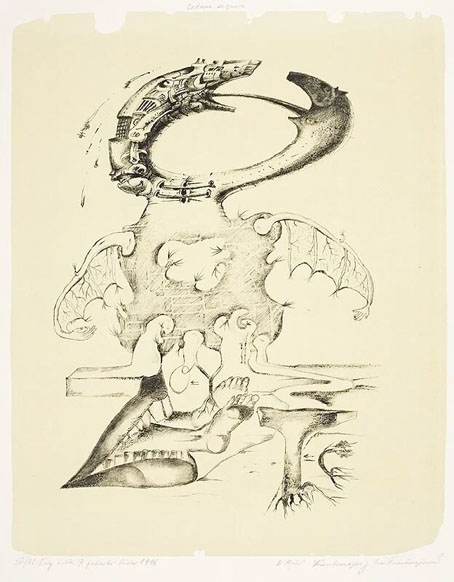

Exquisite Corpse (1927) by André Masson, Max Ernst, Max Morise.

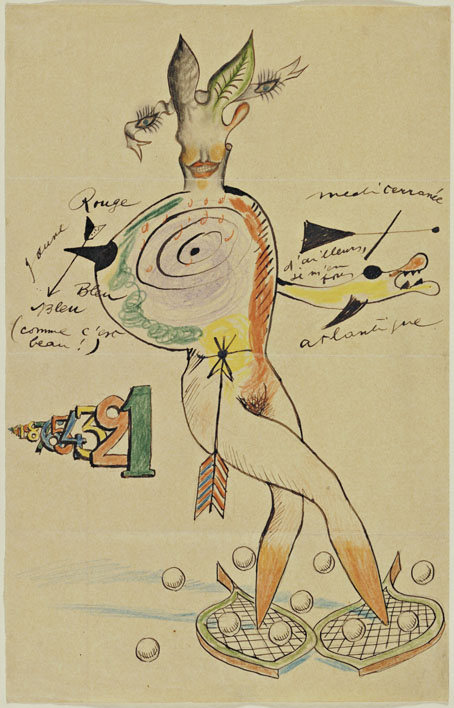

Exquisite Corpse (1928) by Man Ray, André Breton, Yves Tanguy, and Max Morise.

Exquisite Corpse (1928) by Man Ray, Max Morise, André Breton, Yves Tanguy.

Continue reading “The exquisite corpse will drink the new wine”