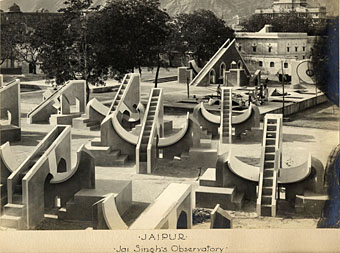

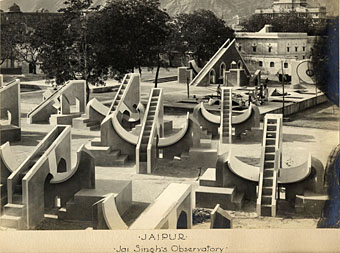

Fran Pritchett’s site has a wealth of photos of Indian architecture, including many old views of temples and a substantial section devoted to Jaipur’s fascinating Jantar Mantar.

The Jantar Mantar is a collection of architectural astronomical instruments, built by Maharaja Jai Singh II at his then new capital of Jaipur between 1727 and 1733. It is modelled after the one that he had built for him at the then Mughal capital of Delhi. He had constructed a total of five such observatories at different locations, including the ones at Delhi and Jaipur. The Jaipur observatory is the largest of these.

The name is derived from yantra, instrument, and mantra, for chanting; hence the ‘the chanting instrument’. It is sometimes said to have been originally yantra mantra, mantra being translated as formula, although there is limited justification for this since in traditional spoken Jaipur language, the locals obfuscate the written Y syllable as J.

The observatory consists of fourteen major geometric devices for measuring time, predicting eclipses, tracking stars in their orbits, ascertaining the declinations of planets, and determining the celestial altitudes and related ephemerides. Each is a fixed and ‘focused’ tool. The Samrat Jantar, the largest instrument, is 90 feet high, its shadow carefully plotted to tell the time of day. Its face is angled at 27 degrees, the latitude of Jaipur. The Hindu chhatri (small domed cupola) on top is used as a platform for announcing eclipses and the arrival of monsoons.

Built of local stone and marble, each instrument carries an astronomical scale, generally marked on the marble inner lining; bronze tablets, all extraordinarily accurate, were also employed. Thoroughly restored in 1901, the Jantar Mantar was declared a national monument in 1948.

An excursion through Jai Singh’s Jantar is the singular one of walking through solid geometry and encountering a collective weapons system designed to probe the heavens.

The instruments are in most cases huge structures. They are built on a large scale so that accuracy of readings can be obtained. The samrat yantra, for instance, which is a sundial, can be used to tell the time to an accuracy of about a minute. Today the main purpose of the observatory is to function as a tourist attraction.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• The Garden of Instruments