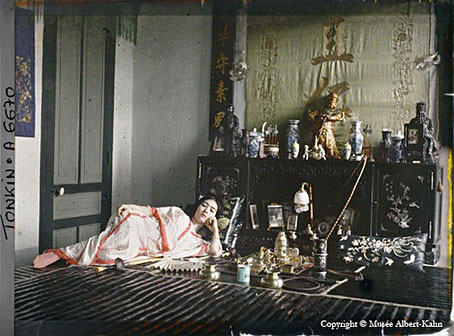

The sculpture known as Antinous Mondragone (c.130 AD).

The planned British Museum exhibition I mentioned in January, a major examination of the Emperor Hadrian’s life and influence, opens today and runs to 26 October, 2008. Hadrian means more to Britons than most Roman Emperors on account of the still-extant wall which bears his name, built to divide England from the untameable wilds of Scotland, or Caledonia as it was then known. On a personal level he fascinates for his obsession with his dead lover Antinous and the mausoleum (later the Castel Sant’Angelo) and villa he left in Rome.

Hadrian was a man of great contradiction in both his personality and reign: a military man and homosexual, he combined ruthless suppression of dissent with cultural tolerance. He reacted with great ferocity against the Jewish Revolt in 132 AD (examples of poignant objects belonging to Jewish rebels hiding in caves near Jerusalem will be included in the exhibition), but he was also a dedicated philhellene, passionate about Greek culture. He took a young Greek male lover, Antinous, who accompanied him on his travels around the empire. In AD 130, Antinous drowned in mysterious circumstances in Egypt. Consumed by grief, Hadrian founded a new city, Antinoupolis, close to the spot where he died and had Antinous declared a god, linked to the Egyptian deity Osiris. A cult of Antinous-Osiris sprang up resulting in statues, busts and silverware featuring the image of the newly deified youth.

And proving that this is a subject whose time has come, John Boorman has a film in production based on Marguerite Yourcenar’s Memoirs of Hadrian. Given Boorman’s uneven output that could be either a good or bad thing; we’ll no doubt find out soon enough.

• A very modern emperor | Mary Beard on Hadrian

• Hadrian’s Wall World Heritage site

• Virtual Museum: Antinous Portraits

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Hadrian and Greek love

• Vedute di Roma

• The Cult of Antinous