A temple to mystery and imagination

| The Large Hadron Collider.

Category: {architecture}

Architecture

Albert Kahn’s Autochromes

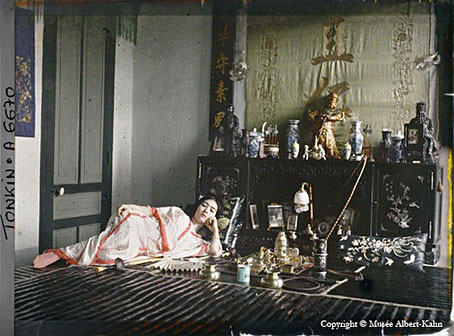

“Lying on a raised dais, this woman may have been the concubine of an affluent opium smoker.” (1915)

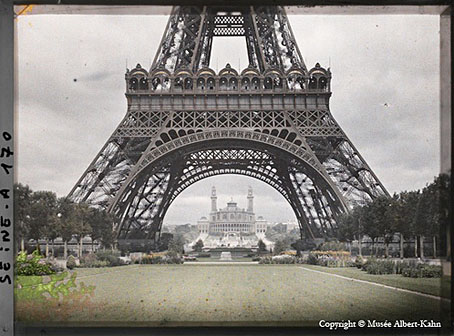

In 1909 the millionaire French banker and philanthropist Albert Kahn embarked on an ambitious project to create a colour photographic record of, and for, the peoples of the world. As an idealist and an internationalist, Kahn believed that he could use the new Autochrome process, the world’s first user-friendly, true-colour photographic system, to promote cross-cultural peace and understanding. More.

More Albert Kahn Autochromes and similar early views in colour at this Flickr pool.

Update: And there’s The Wonderful World of Albert Kahn, site and book.

The Palais du Trocadéro from the Eiffel Tower (1912).

Previously on { feuilleton }

• The Palais du Trocadéro

• The Dawn of the Autochrome

• German opium smokers, 1900

Old lighthouses

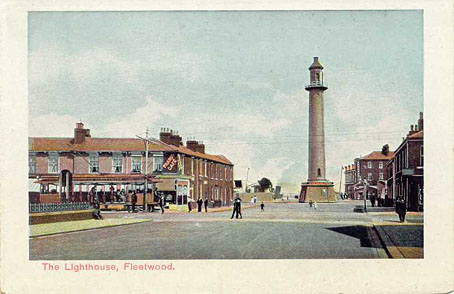

From a collection of old postcards depicting British lighthouses. My own fascination with these structures can be traced directly to these two particular examples. The Lower Light or Beach Lighthouse is positioned a couple of streets away from the nursing home where I was born. Although we never lived in Fleetwood, I grew up a few miles down the coast and we often made trips to this unusual port which 19th century entrepreneurs built from nothing in the 1830s.

The lighthouses were built in the 1840s, intended to function together as a guide to ships approaching the docks through sandbanks. To me they helped augment the town’s curious edge-of-the-world quality. Fleetwood is positioned at the end of a peninsular, surrounded by the Irish Sea on two sides with the estuary of the River Wyre on the third. The trams which travel the length of the coast have to make a loop around a block of buildings when they reach the Pharos lighthouse and head south again. A lighthouse built in the middle of a residential street seemed completely bizarre when I was a child; it still looks strange now, as though it was dropped there then forgotten. Once you’ve reached it there’s nowhere left to go. (Well, unless you take the ferry over the river….) Its modest companion is more naturally situated on the promenade nearby. This Flickr photo shows how it looks today.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Hungarian water towers

Viollet-le-Duc

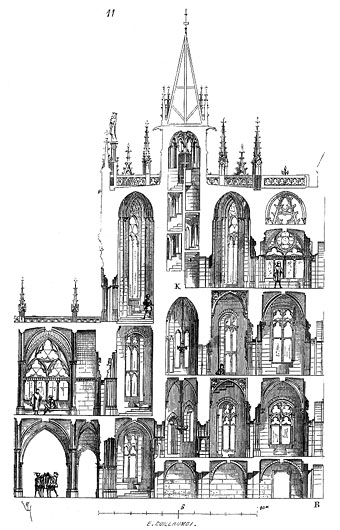

One of a great quantity of Gothic studies by French architect Eugène Viollet-le-Duc at Wikimedia Commons. Also in the Commons is a large selection of photographs and drawings of the fortified city of Carcassonne which the architect controversially restored.

Elizabetes Iela 10b, Riga

Paris and Brussels are well-known centres of Art Nouveau architecture, less well-known but equally valuable is the Latvian capital of Riga whose historic centre is now a World Heritage Site. The highly distinctive building at Elizabetes Iela 10b is one of a number of buildings there designed by Mikhail Eisenstein, father of film director Sergei Eisenstein. The giant decorative heads are quite unique, and I also like the peacock and other mascarons. One can’t help but think that this façade—in a street full of equally detailed façades—would have sustained a lot more attention had it been built in a European capital.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Atelier Elvira

• Louis Bonnier’s exposition dreams

• The Maison Lavirotte

• The House with Chimaeras