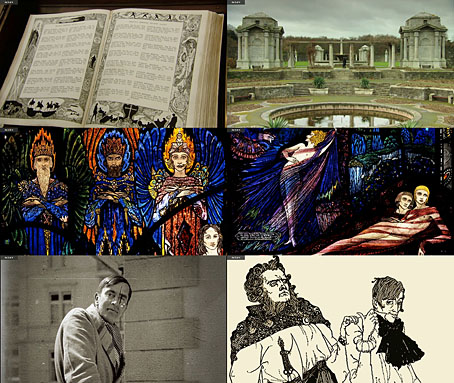

An all-too-short run through the biography of Harry Clarke, Fire in the Blood was made by Irish TV channel RTE in 2016 as part of a series devoted to the Celtic Revival. Camille O’Sullivan is the guide to Clarke’s life and work in a film which includes some commentary from Clarke expert Nicola Gordon Bowe, among others. 24 minutes isn’t enough time to cover the full range of the artist’s work but any Clarke documentary is better than none, and this one has a number of points in its favour. Clarke’s stained-glass windows are given a prominent place in the discussion, a reminder that stained-glass production was Clarke’s primary business even while his success as an illustrator increased. The stained-glass medium is an especially attractive one for a TV documentary—the colours of the windows glow on the screen in a manner they can never do on a page—and you could easily fill an hour with a discussion of Clarke’s remarkable glasswork alone. The end of the film includes some discussion about the scandal of Clarke’s last major work in the medium, the so-called Geneva Window, commissioned by the Irish government as a gift for the League of Nations then disowned when Clarke’s choice of subject (and the manner of its depiction) was deemed unsuitable. As with earlier objections to the work of Aubrey Beardsley, the complaints seem scarcely credible today but the window ended up being sold to an American collector.

On the illustration side we get to see pages from a little-known work of Clarke’s, the frame designs for the pages in Ireland’s Memorial Records, a multi-volume record of the names of Irish soldiers who died in the First World War. Nicola Gordon Bowe’s Clarke studies show the title page but seeing all the frames in print wasn’t possible until the publication of Harry Clarke’s War by Marguerite Helmers. The silhouettes of the soldiers embedded in each frame form a sequential narrative describing the progress of the war amid knotted borders that hark back to the page designs of the Book of Kells.

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The illustrators archive

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Harry Clarke’s illustrated Swinburne

• More Harry Clarke online

• Harry Clarke online

• Harry Clarke record covers

• Thomas Bodkin on Harry Clarke

• Harry Clarke: His Graphic Art

• Harry Clarke and others in The Studio

• Harry Clarke’s Fairy Tales of Charles Perrault

• Harry Clarke in colour

• The Tinderbox

• Harry Clarke and the Elixir of Life

• Cardwell Higgins versus Harry Clarke

• Modern book illustrators, 1914

• Illustrating Poe #3: Harry Clarke

• Strangest Genius: The Stained Glass of Harry Clarke

• Harry Clarke’s stained glass

• Harry Clarke’s The Year’s at the Spring

• The art of Harry Clarke, 1889–1931

John I had mentioned the possibility in one of your earlier posts a while back about Clarke’s work but this summer past I was finally able to visit the Wolfson Museum at Florida International University in Miami Beach. I’m not kidding. The Wolfson is only 0.25 miles (395 meters) from the beach, a totally improbable site for such a work! Well Dublin’s loss.

What can I say? It was as beautiful and stunning as you can imagine. The window was in storage from 2020 to 2023 and they constructed a new setting, nicely illuminated, for it and some related pieces. I was fortunate that I was able to go in the morning of a weekday so there was a minimal crowd. I was able to enjoy some time by myself.

Here is a link to the Wolfson site about the Window. Scroll down a bit to the Object Highlights and you can download a PDF of the installation checklist.

There isn’t a publication associated directly with the display. The museum shop had both of Lucy Costigan’s books which I already possessed.

Yes, I remember you mentioning an intended visit to see the window. I’ve yet to see any of Clarke’s glasswork in situ. I really ought to get to Dublin some time, it’s only a short plane ride away and the museum there has a number of Clarke’s drawings and paintings in their collection.

You’ve missed the chance to see the Eve of St. Agnes glass I’m aftaid, John – at least for 5 or 5 years, the Hugh Lane Gallery is closed for extensive renovations as of last autumn.

There is some other work in the National Gallery and in several churches, but the stuff in the Hugh Lane was a real highlight.