WAR IS PEACE

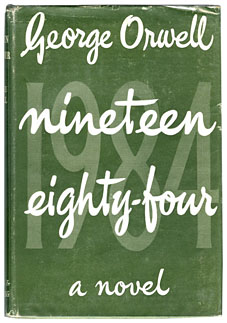

Nineteen Eighty-Four, 1949

“I just want you to know that, when we talk about war, we’re really talking about peace.” George W. Bush, June 18, 2002

George Orwell’s classic novel was published fifty-seven years ago today. There’s little reason to remind anyone of its prescience or the ubiquity of the neologisms Orwell invented; examples like the one above are all too easy to find in the current political landscape. That prescience can also be seen in his essay ‘Politics and the English Language‘ written in 1946, which shows how much his mind was engaged with the use of language and its relationship to politics shortly before he began writing the novel. The extract below is especially pertinent and worth bearing in mind whenever you hear a politician talking.

In certain kinds of writing, particularly in art criticism and literary criticism, it is normal to come across long passages which are almost completely lacking in meaning. Words like romantic, plastic, values, human, dead, sentimental, natural, vitality, as used in art criticism, are strictly meaningless in the sense that they not only do not point to any discoverable object, but are hardly ever expected to do so by the reader. When one critic writes, “The outstanding feature of Mr. Xs work is its living quality,” while another writes, “The immediately striking thing about Mr. X’s work is its peculiar deadness,” the reader accepts this as a simple difference of opinion. If words like black and white were involved, instead of the jargon words dead and living, he would see at once that language was being used in an improper way.

Many political words are similarly abused. The word Fascism has now no meaning except insofar as it signifies “something not desirable.” The words democracy, socialism, freedom, patriotic, realistic, justice, have each of them several different meanings which cannot be reconciled with one another. In the case of a word like democracy, not only is there no agreed definition, but the attempt to make one is resisted from all sides. It is almost universally felt that when we call a country democratic we are praising it: consequently the defenders of every kind of regime claim that it is a democracy, and fear that they might have to stop using the word if it were tied down to any one meaning.

Words of this kind are often used in a consciously dishonest way. That is, the person who uses them has his own private definition, but allows his hearer to think he means something quite different. Statements like Marshal Petain was a true patriot, The Soviet Press is the freest in the world, The Catholic Church is opposed to persecution, are almost always made with intent to deceive. Other words used in variable meanings, in most cases more or less dishonestly, are class, totalitarian, science, progressive, reactionary, bourgeois, equality.