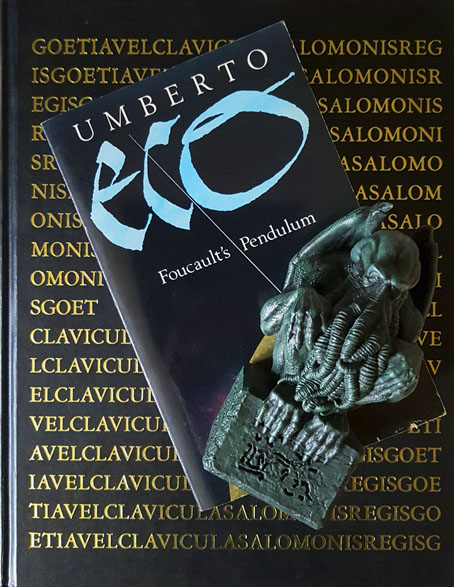

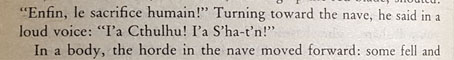

In which Umberto Eco nods fleetingly to the Cthulhu Mythos near the end of his second novel, Foucault’s Pendulum. I’d show you more of the relevant passage (below) but it’s rather spoilerish if you haven’t read the book. This turned up during a re-reading, my first since the novel appeared in paperback in 1990. A reference like this doesn’t stand out as much as it might elsewhere, not when the text that precedes it is stuffed to the gills with esoterica. Several hundred pages of occult history made me forget that Eco had hauled Lovecraft into his compendious fabulation along with everything else.

Ishmael Reed was responsible for returning me to Eco’s novel as a result of an earlier re-read of Mumbo Jumbo, Reed’s fictional account of voodoo, jazz, politics and many other things in the America of the 1920s. Eco was already in mind prior to this since I’d been working my way through his essays and lectures. (As I still am. He wrote a lot of the things.) Mumbo Jumbo‘s exploration of occult knowledge and occult conspiracy summoned vague memories of Foucault’s Pendulum, which made me realise that I didn’t remember very much at all about Eco’s novel even though both books share an interest in the tangled history of the Knights Templar. To the top of the pile it went.

It’s been interesting reading Eco’s novel again. For a start, it was funnier than I remembered, although this may be a result of my being much more familiar with the publishing business than I was in 1990. The story concerns a trio of men who work for a small publishing house in Milan, a division of which is devoted to the works of self-financing authors or “SFAs”. A vanity press in other words. A potential SFA turns up with a crank book rather similar to The Holy Blood and the Holy Grail, then abruptly disappears without collecting his manuscript. Curiosity, idleness and invention inspire the trio to improve upon the manuscript’s occult conspiracy in a manner that knits together just about every aspect of Western mysticism there is, and even some of the Eastern ones: Rosicrucianism, alchemy, the Kabbalah, Atlantis, the Illuminati, ley lines, the Hollow Earth, Stonehenge, etc, etc; it’s all in there. This is the thing they eventually call “the Plan”, a kind of Unified Field Theory of esoteric knowledge, and a contrivance whose fabrication is assisted by further SFA manuscripts arriving as candidates for a new line of “Hermetic” books. Problems arise for the publishers when their elaborate intellectual game ends up being taken for a serious revelation by a group of fanatical mystics. Eco’s novel demonstrates the pleasures of creative apophenia—the trio are continually challenging each other to fit a new piece of historical data into their scheme—while also acting as a warning that any halfway plausible Plan has the potential to be taken seriously by credulous cranks. As Lia, the novel’s voice of reason, says:

People are starved for plans. If you offer them one, they fall on it like a pack of wolves. You invent, and they’ll believe. It’s wrong to add to the inventings that already exist.

Eco explored this phenomenon more seriously in a later novel, The Prague Cemetery, which invents an author for the notorious Protocols of the Elders of Zion, a Plan whose conspiratorial claims continue to fuel anti-Semitism the world over. The internet has only accelerated Plan-construction, and I imagine Eco would have been simultaneously fascinated and appalled by the feeble imaginings of that ex-football player with the lizard obsession, and the shambling, frothing Q-mob with their Very Important jpegs. (What is it the latter are always saying? “Trust the Plan”… And having mentioned Mr Icke, I just put his name into Google only to find that the latest extract from his Twitter feed has him talking about the Holy Grail. Welcome to the Crank Zone.)

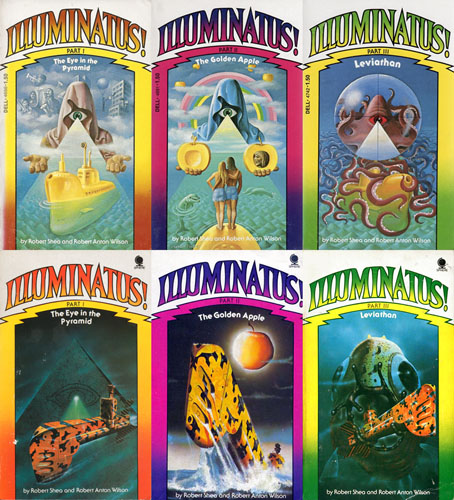

Upper row: Dell paperbacks illustrated by Carlos Victor, 1975; lower row: Sphere paperbacks illustrated by Tony Roberts, 1976–77. The novel was originally published in three parts but was always intended to be a single book, as it is in later printings.

Someone once said that beneath or behind all political and cultural warfare lies a struggle between secret societies. Another author suggested that the Nursery Rhyme and the book of Science Fiction might be more revolutionary than any number of tracts, pamphlets, manifestoes of the political realm.

Ishmael Reed, Mumbo Jumbo

Reed’s words are paraphrased in an epigraph that appears in the opening pages of Illuminatus! by Robert Shea and Robert Anton Wilson, one of the precursors of Foucault’s Pendulum, and a novel with a more generic approach to all-encompassing conspiracy theory. I doubt that the Eco readers who shun “sci-fi” would be aware of this but Eco himself certainly seemed to be; there in his library of references you’ll find mention of a minor occult group that I took to be a veiled nod to Robert Anton Wilson. (Rather than elaborate I’ll leave it as something for Discordian readers to discover.) Where Eco’s invention is (mostly) pieced together from old Hermetic manuscripts with Latin titles like Utriusque Cosmi Historia, Shea and Wilson mine the contents of the 20th-century crank bookshelf along with generous helpings from the popular culture of their time, especially the psychedelic culture of the 1960s. Consequently, there’s a lot more Lovecraftian reference in Illuminatus!—the Pentagon, for example, turns out to have been given its shape in order to contain the bound energies of Yog-Sothoth—while Lovecraft himself is one of the novel’s many characters. The correspondences between the two novels are deepened if you know that Shea and Wilson first had the idea for Illuminatus! while working as associate editors at Playboy magazine in the 1960s. The many conspiracy-obsessed letters they received were fuel for their imaginations in the same way as the manuscripts submitted to Eco’s publishing trio. Illuminatus! was the result of Shea and Wilson asking themselves what it would be like if all these conspiracies were true.

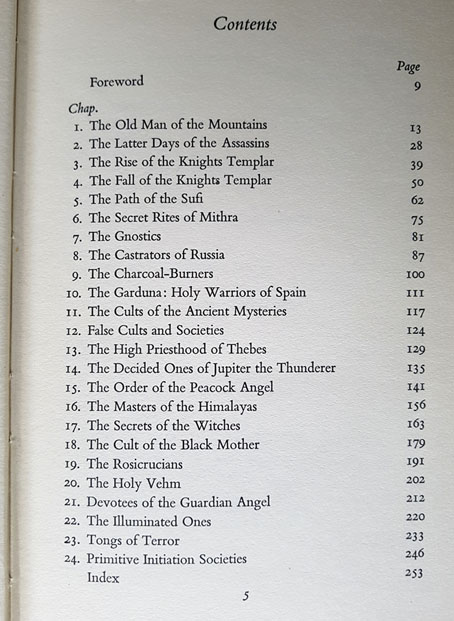

Table of contents from Secret Societies (1961) by Arkon Daraul/Idries Shah.

I remember someone on Twitter a few years ago wondering whether a portion of the current conspiracy mania could be laid at Robert Anton Wilson’s door. I said I couldn’t see it. Illuminatus! is a very self-referential novel which works to increase the reader’s scepticism rather than undermine it, a process that Wilson continued in his later books. As with Foucault’s Pendulum, most of what Shea and Wilson were writing about was already in the public sphere; someone even complained to me once that there wasn’t anything original about Illuminatus! at all. (I disagreed. fnord) There was plenty of this stuff around before Shea and Wilson arrived, and a lot more that came after them. Secret Societies by Idries Shah (writing as Arkon Daraul) is a book referred to several times in Illuminatus!; in it you’ll find chapters on all the cults and cult figures dealt with in the novels of Eco, Shea and Wilson, together with many lesser-known sects. Pauwels and Bergier’s The Morning of the Magicians is another prior text that Eco, Shea and Wilson all refer to, as well as being a book responsible for entire sub-genres in the Crank Zone. Pauwels and Bergier referred to their methodology as “Fantastic Realism”, a term that allowed some room for manoeuvre when it seemed they were straying too close to outright fiction.

One of Umberto Eco’s favourite writers, Jorge Luis Borges, said he liked to regard metaphysics as a branch of fantastic literature; you can do the same with the crank bookshelf if you’re so inclined, and even make a lot of money if you get the ingredients right. The Indiana Jones franchise is the Crank Zone strained through the conventions of the matinee serial: films 1 and 3 riff on ideas from Trevor Ravenscroft’s Spear of Destiny, and Pauwel and Bergier’s Nazi occultism, while film 4 is Cold War paranoia, Area 51 and ancient astronauts. Extensions of the franchise in other media have taken in Atlantis and the Hollow Earth. The Eco, Shea and Wilson novels go much further, they share a complexity you seldom find elsewhere in this area. Illuminatus! may be a genre novel but it’s also freighted with serious appendices, footnotes and bibliographic references. The most popular conspiracies are distinguished not by their complexity but by the poverty of their schemata: plots that sound like Gothic melodrama, bad science fiction or Dennis Wheatley after he’s spent the afternoon raiding his wine cellar. The cerebrally-challenged want an elevator pitch, not an intertextual entertainment that rattles on for 800 pages, contradicting itself while it unfolds. Robert Anton Wilson was fond of quoting the famous line from Science and Sanity by Alfred Korzybski: “A map is not the territory”; Umberto Eco, being a good semiotician, uses the same quote as an epigraph for chapter 83 of Foucault’s Pendulum. It’s a simple enough statement but a lesson that many people still have difficulty learning.

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The Lovecraft archive

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Crank book covers

• Morning of the Magicians book covers

Thank you so much for reminding me of Foucault’s Pendulum! I read it in my 20’s and was already much inspired by the Illuminati Trilogy (although an attempt to re read that proved to me that it was very much a product of its time)

I’m now very curious to read Mumbo Jumbo. I’m guessing that you’ve read Jake Arnott’s House of Rumour?

Familiar with all these works (what does that say about one?) and greatly enjoyed this article!

Richie: Thanks. I’ve been thinking of re-reading Illuminatus! as well–it’s a very long time since I last read it–but I really ought to read some new books instead of going back over old ones. Mumbo Jumbo is very entertaining and informative. Also rather post-modern (for want of a better term) in the way it incorporates pictures and photographs, some of them anachronistically from the late 60s/early 70s.

Michael: Thanks also!