Cardiff Docks (1894) by Lionel Walden.

There’s a tendency to consider the art of the 19th century as being preoccupied with the rural, the mystical and the historic: all true in the case of the Pre-Raphaelites. But the effects of the Industrial Revolution attracted enough artists to create a sub-genre of painting that takes the miasmas of factories and the hellish glow of furnaces as its subject; Philip de Loutherbourg’s Coalbrookdale by Night (1801) is one of the more well-known examples, not least for being a painting that shows the future emerging from a rural landscape in a truly infernal manner.

Lionel Walden (1861–1933) was an American artist who was in Wales long enough to paint several scenes of the Cardiff docks and the steelworks. I’d not seen this gorgeously atmospheric painting of the docks before but it captures the light and the ambience of a British autumn/winter with the same fidelity as John Atkinson Grimshaw, an artist who made chilly mornings and smoky twilights his speciality. Walden’s other paintings are a lot lighter, with more traditional views of docks, boats and fishermen. (Via Beautiful Century.)

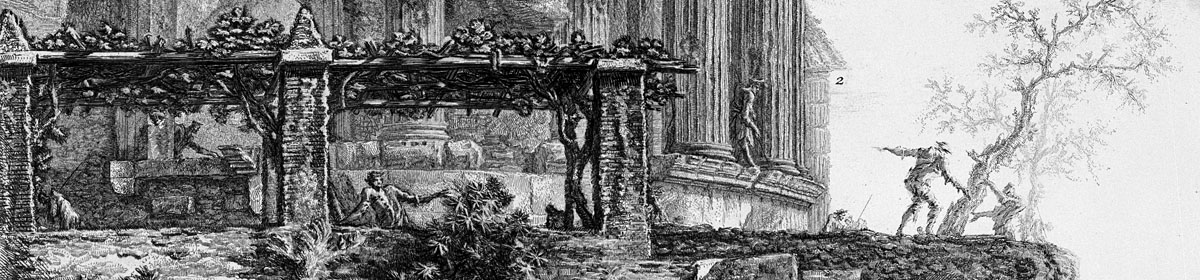

The Steelworks, Cardiff at Night (1893–97) by Lionel Walden.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• How It Works

• The art of John Atkinson Grimshaw, 1836–1893