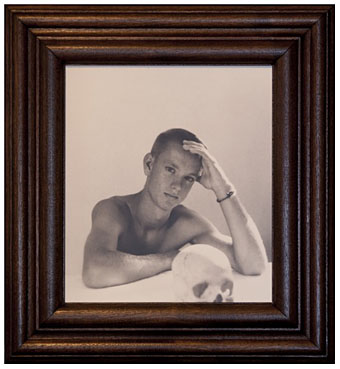

Named After Vermeer (2010); silver gelatin print.

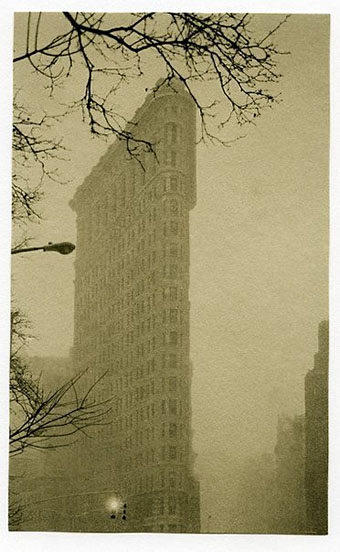

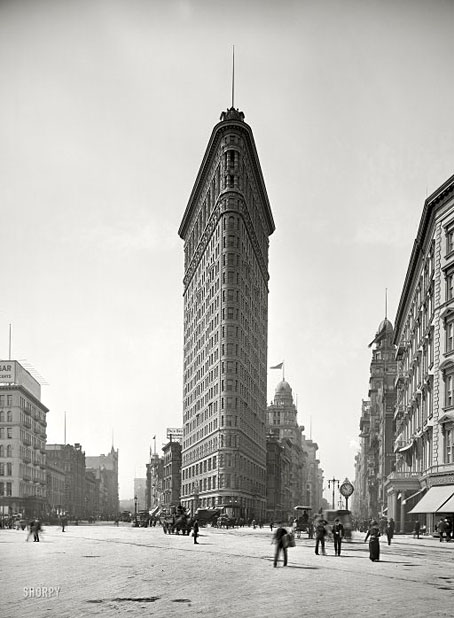

Wessel + O’Connor Fine Art resumed business recently following a hiatus and a change of location. Their current exhibition is a presentation of prints by American photographer Jefferson Hayman whose use of silver gelatin and platinum processes returns photography to the diffuse atmospheres of its earliest days. Some of these works are barely distinguishable from their predecessors; in the case of the Flatiron view below (inevitably bringing to mind the famous picture by Edward Steichen) only the street light and traffic signals give any indication that it’s a recent photo. (Luther Gerlach has used an antique camera and old print processes to similar effect in Los Angeles.) Jefferson Hayman Camera Works runs to February 27th.

The Flatiron (2003); platinum print.

Previously on { feuilleton }

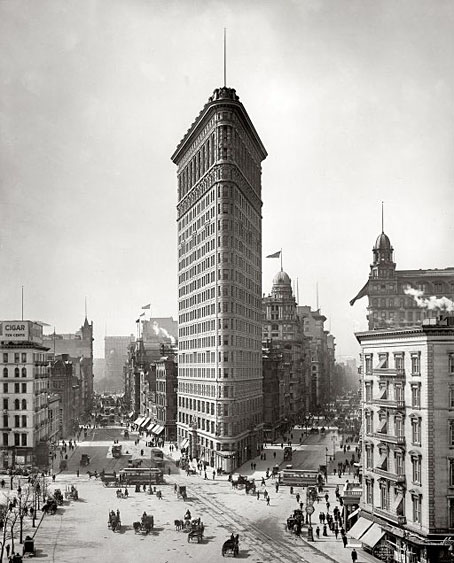

• The Flatiron Building

• Luther Gerlach’s Los Angeles

• Edward Steichen