The Red Shoes: Moira Shearer and Léonide Massine.

Emeric is often too easily accused of basing the principal male character of The Red Shoes on Serge Diaghilev, to which he replies: “There is something of Diaghilev, something of Alex Korda, something of Michael, and quite a little bit of me.”

Michael Powell, A Life in Movies (1986)

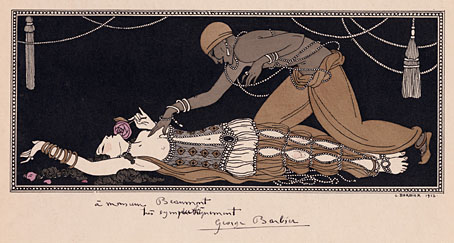

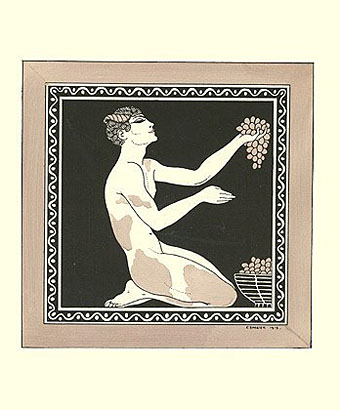

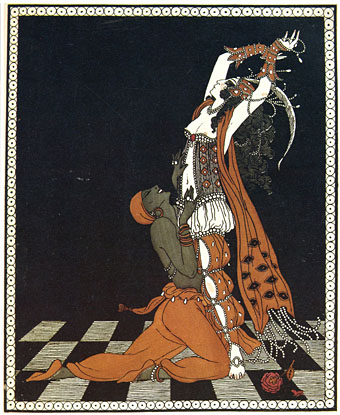

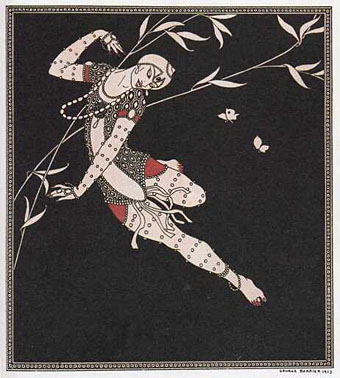

Despite Emeric Pressburger’s qualificatory comments, there’s a lot more of the Ballets Russes in Powell and Pressburger’s film of The Red Shoes (1948) than first meets the eye. Or so I discovered, since I’d known about the film via my ballet-obsessed mother for years before I’d even heard of Diaghilev or Stravinsky. The most obvious connection is the presence of Léonide Massine who took the leading male roles in Diaghilev’s company following the departure of Nijinsky. He also choreographed Parade, the ballet which featured an Erik Satie score and designs by Picasso. The fraught relationship between Diaghilev and Nijinsky forms the heart of The Red Shoes: Anton Walbrook’s impresario, Boris Lermontov, is the Diaghilev figure while the brilliant dancer who obsesses him, and for whom he creates the ballet of The Red Shoes, is Moira Shearer as Victoria Page. That the dancer happens to be a woman is a detail which makes the film “secretly gay”, as Tony Rayns once put it. Diaghilev and Nijinsky were lovers, and fell out when Nijinsky married; in The Red Shoes Lermontov demands that Vicky choose between a life of art or a life of marriage to composer Julian Craster (Marius Goring). She chooses love but ends up drawn back to art, with tragic consequences that mirror the Hans Christian Andersen story. That story, of course, ends with a young woman dancing herself to death after donning the fatal shoes, a dénouement that’s unavoidably reminiscent of The Rite of Spring.

Anton Walbrook as Lermontov.

Lermontov: Why do you want to dance?

Vicky: Why do you want to live?

Other parallels may be found if you look for them, notably the figure of Julian Craster who comes to Lermontov as a young and unknown composer just as Stravinsky did with Diaghilev. Craster’s music isn’t as radical as Stravinsky but The Red Shoes was already giving the audience of 1948 enough unapologetic Art with a capital “A” without dosing them with twelve-tone serialism. The film aims for the same combination of the arts as that achieved by Diaghilev, especially in the long and increasingly fantastic ballet sequence. This was another of Powell’s shots at what he called “a composed film” in which dramaturgy and music work to create something unique. The Red Shoes is a film that’s deadly serious about the importance of art, a rare thing in a medium which is so often at the mercy of Philistines. In the past I’ve tended to favour other Powell and Pressburger films, probably because I’ve taken The Red Shoes for granted for so long. But the more I watch The Red Shoes the more it seems their greatest film, even without this wonderful train of associations. The recent restoration is out now on Blu-ray, and it looks astonishing for a film that’s over sixty years old.

Seeing as this week has been all about The Rite of Spring, here’s a few more centenary links:

• Stravinsky’s The Rite of Spring, Visualized in a Computer Animation for its 100th Anniversary

• George Benjamin on How Stravinsky’s Rite of Spring has shaped 100 years of music

• Strange Flowers visits the Théâtre des Champs-Elysées

Previously on { feuilleton }

• The Rite of Spring, 2001

• The Rite of Spring, 1970

• The Rite of Spring reconstructed