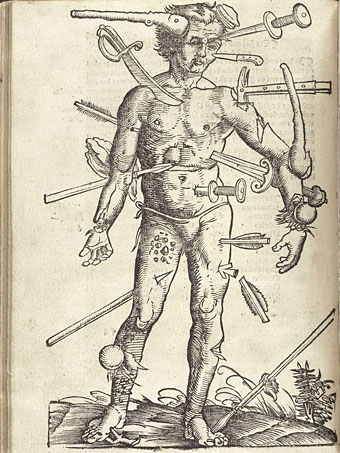

Wound Man from Feldbuch der Wundarzney (Field Book of Surgery, 1517).

For years I wondered about the precise appearance of Wound Man after reading the following in Red Dragon (1981) by Thomas Harris:

“It was a coincidence,” Graham said. “The sixth victim was killed in his workshop. He had woodworking equipment and he kept his hunting stuff out there. He was laced to a pegboard where the tools hung and he was really torn up, cut and stabbed and he had arrows in him. The wounds reminded me of something. I couldn’t think what it was.”

“And you had to go on to the next ones.”

“Yes. Lecter was very hot – he did the next three in nine days. But this sixth one, he had two old scars on his thigh. The pathologist checked with the local hospital and found he had fallen out of a tree-blind five years before while he was bow hunting and stuck an arrow through his leg.

“The doctor of record was a resident surgeon, but Lecter had treated him first – he was on duty in the emergency room. His name was on the admissions log. It had been a long time since the accident, but I thought Lecter might remember if anything had seemed fishy about the arrow wound, so I went to his office to see him. We were grabbing at anything then.

“He was practicing psychiatry by that time. He had a nice office. Antiques. He said he didn’t remember much about the arrow wound, that one of the victim’s hunting buddies had brought him in, and that was it.

“Something bothered me though. I thought it was something Lecter had said or something in the office. Crawford and I hashed it over. We checked the files and Lecter had no record. I wanted some time in his office by myself but we couldn’t get a warrant. We had nothing to show. So I went back to see him.

“It was Sunday, he saw patients on Sunday. The building was empty except for a couple of people in his waiting-room. He saw me right away. We were talking and he was making this polite effort to help me and I looked up at some very old medical books on the shelf above his head. And I knew it was him.

“When I looked at him again maybe my face changed, I don’t know. I knew it and he knew I knew it. I still couldn’t think of the reason though. I didn’t trust it. I had to figure it out. So I mumbled something and got out of there, into the hall. There was a pay phone in the hall. I didn’t want to stir him up until I had some help. I was talking to the police switchboard when he came out of a service door behind me in his socks. I never heard him coming. I felt his breath was all and then – there was the rest of it.”

“How did you know, though?”

“I think it was maybe a week later in the hospital I finally figured it out. It was Wound Man – an illustration they used in a lot of the early medical books like the ones Lecter had. It shows different kinds of battle injuries, all in one figure. I had seen it in a survey course a pathologist was teaching at G.W.U. The sixth victim’s position and his injuries were a close match to Wound Man.”

“Wound Man, you say? That’s all you had?”

“Well, yeah. It was a coincidence that I had seen it. A piece of luck.”

With the proliferation of online archives mysteries no longer stay unresolved for very long. There’s more than one Wound Man to be discovered, but the one that’s reproduced most often is probably the same one to which Harris refers. Feldbuch der Wundarzney by Hans von Gersdorff features a number of illustrations which turn up in later textbooks, if only as examples of the hazards of medieval medicine. Wound Man is one of the more popular examples, as is this illustration showing the treatment of a head wound which I think I used somewhere inside The Thackery T Lambshead Pocket Guide to Eccentric and Discredited Diseases (2003). Wound Man has also seen service in one of my book designs, appearing on the contents pages of Lucy Swan’s The Adventures of Little Lou in 2007.