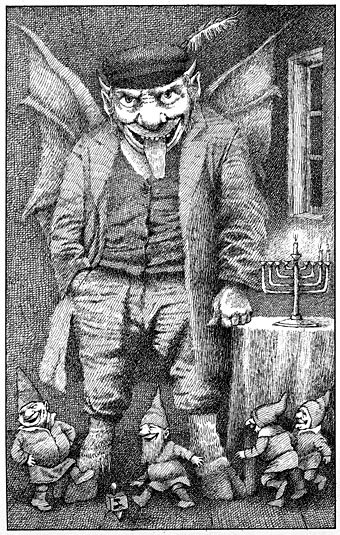

From Zlateh the Goat and Other Stories (1966) by Isaac Bashevis Singer.

All the obituaries of the late Maurice Sendak have focused inevitably on Where the Wild Things Are. That gives me a chance to draw attention to some less familiar Sendak drawings whose finer crosshatching naturally appeals to an inveterate crosshatcher such as myself. The combination of bold characterisation and dense shading makes these pieces look remarkably similar to Mervyn Peake’s illustrations of the 1940s. Sendak spoke to Nick Meglin about some of the influences on his drawing in The Art of Humorous Illustration (1973). Given what he says here it’s evident that he and Peake (who also admired Cruikshank and Rowlandson) shared antecedents:

Many of the artists who influenced me were illustrators I accidentally came upon. I knew the Grimm’s Fairy Tales illustrated by George Cruikshank. I just went after everything I could put my hands on illustrated by Cruikshank and copied his style. It was quite as simple as that. I wanted to crosshatch the way he did. Then I found Wilhelm Busch and I was off again. But happily Wilhelm Busch also crosshatched so the Cruikshank crosshatching wasn’t entirely wasted. And so an artist grows. I leaned very heavily on these people. I developed taste from these illustrators.

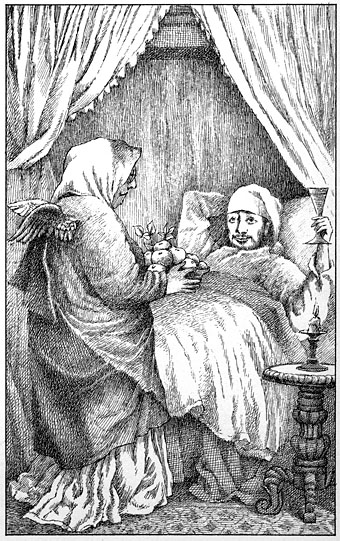

The 1860’s, the great years of the English illustrators from whom so much of my work is derived, are familiarly known as “the sixties” to admirers of Victorian book illustration. The influence of Victorian artists such as George Pinwell and Arthur Hughes, to name just two, is evident in the pictures I created for Higglety Pigglety Pop! (Harper and Row, 1967), Zlateh the Goat (Harper and Row, 1966), and A Kiss for Little Bear (Harper and Row, 1968). And I’ve learned from other English artists as well. Randolph Caldecott gave me my first demonstration of the subtle use of rhythm and structure in a picture book. Hector Protector and As I Went Over the Water (Harper and Row, 1965) is an intentionally contrived homage to this beloved teacher.

From Zlateh the Goat and Other Stories (1966) by Isaac Bashevis Singer.

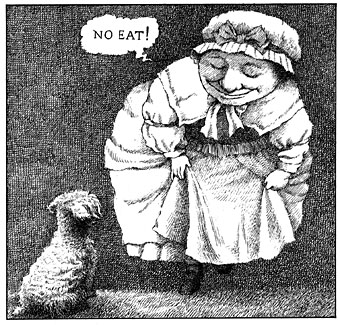

For other fine points in picture book making, I’ve studied the works of Beatrix Potter and William Nicholson. Nicholson’s The Pirate Twins certainly influenced Where the Wild Things Are (Harper and Row, 1963).

A retrospective of my English passion can be found in Lullabies and Night Songs (Harper and Row, 1965). The illustrations for this book, which skip from Rowlandson to Cruikshank to Caldecott and even to Blake, are a noisy pastiche of styles, though I believe they still resonate with my own particular sound. Mr. Rabbit and the Lovely Present (Harper and Row, 1962) is as far as I am aware the only book I’ve done that reveals my admiration for Winslow Homer.

Higglety Pigglety Pop! Or, There Must Be More to Life (1967).

About two-and-a-half years after the publication of Where the Wild Things Are, I finally became conscious of my reviving interest in the art I’ve experienced and loved as a child. The trigger was an exhibit (at The Metropolitan Museum) of pages from Little Nemo in Slumberland, Winsor McCay’s famous newspaper comic strip of the years 1905 to 1911. Before the exhibit I was ignorant of this popular American artist’s pure genius for graphic fantasy. It now sent me scooting back with new eyes to the popular art of my own childhood.

This recognition of personal roots is in no way meant as a triumphant revelation or as reverse snobbism, a put-down of my earlier, more ‘refined’ influences. What I’ve learned from English as well as French and German artists will, if I have my wish, become more absorbed into my creative psyche, blending and living peaceably with my own slice of the past. But of course all this happens on its own or it doesn’t happen at all.

Elsewhere on { feuilleton }

• The illustrators archive