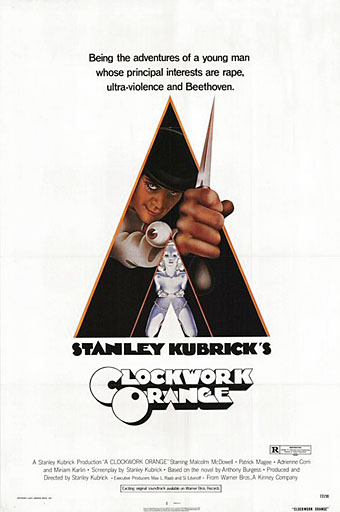

Philip Castle’s poster design. Castle also created the artwork for Full Metal Jacket.

Searching through old magazines whilst researching the epic Barney Bubbles post turned up this, a short reaction by Anthony Burgess to the success of Stanley Kubrick’s Clockwork Orange. Burgess became increasingly ambivalent about the attention brought about by Kubrick’s adaptation, not least because of the way it dominated the rest of his career; some of that ambivalence is already in evidence here.

Juice from A Clockwork Orange

by Anthony Burgess

Rolling Stone, June 8th, 1972

WHEN IT WAS first proposed about eight years ago, that a film be made of A Clockwork Orange, it was the Rolling Stones who were intended to appear in it, with Mick Jagger playing the role that Malcolm McDowell eventually filled. Indeed, it was somebody with the physical appearance and mercurial temperament of Jagger that I had in mind when writing the book, although pop groups as we know them had not yet come on the scene. The book was written in 1961, when England was full of skiffle. If I’d thought of giving Alex, the hero, a surname at all (Kubrick gives him two, one of them mine), Jagger would have been as good a name as any: it means “hunter,” a person who goes on jags, a person who doesn’t keep in line, a person who inflicts jagged rips on the face of society. I did use the name eventually, but it was in a very different novel—Tremor of Intent—and meant solely a hunter, and a rather holy one.

I’ve no doubt that a lot of people will want to read the story because they’ve seen the movie—far more than the other way around—and I can say at once that the story and the movie are very like each other. Indeed, I can think of only one other film which keeps as painfully close to the book it’s based on—Polanski’s Rosemary’s Baby. The plot of the film is that of the book, and so is the language, although naturally there’s both more language and more plot in the book than in the film. The language used by Alex, my delinquent hero, is called Nadsat—the Russian suffix used in making words like fourteen, fifteen, sixteen—and a lot of the terms he employs are derived from Russian. As these words are filtered through an English-speaking mind, they take on meanings and associations unknown to Russians. Thus, Alex uses the word horrorshow to designate anything good—the Russian root for good is horosh—and “fine, splendid, all right then” is the neuter form we ought really to spell as chorosho (the ch is guttural, as in Bach). But good to Alex is tied up with performing horrors, and when he is made what the State calls good it is through the witnessing of violent films—genuine horror shows. The Russian golova—meaning head—is domesticated into gulliver, which reminds the reader he is taking in a piece of social satire, like Gulliver’s Travels. The fact that Russian doesn’t distinguish between foot and leg (noga for both) and arm and hand (ruka) serves—by suggesting a mechanical doll—to emphasise the clockwork-view of life that Alex has: first he is self-geared to be bad, next he is state-geared to be good.

The title of the book comes from an old London expression, which I first heard from a very old Cockney in 1945: “He’s as queer as a clockwork orange” (queer meaning mad, not faggish). I liked the phrase because of its yoking of tradition and surrealism, and I determined some day to use it. It has rather specialised meanings for me. I worked in Malaya, where orang means a human being, and this connotation is attached to the word, as well as more obvious anagrams, like organ and organise (an orange is, a man is, but the State wants the living organ to be turned into a mechanical emanation of itself). Alex uses some Cockney expressions, also Lancashire ones (like snuff it, meaning to die), as well as Elizabethan locutions but his language is essentially Slav-based. It was essential for me to invent a slang of the future, and it seemed best to come from combining the two major political languages of the world—irony here, since Alex is very far from being a political animal. The American paperback edition of A Clockwork Orange has a glossary of Nadsat terms, but this was no idea of mine. As the novel is about brainwashing, so it is also a little device of brainwashing in itself or at least a carefully programmed series of lessons on the Russian language. You learn the words without noticing, and a glossary is unnecessary. More—because it’s there, you tend to use it, and this gets in the way of the programming.

As the novel was written over ten years ago (and planned nearly 30 years ago), and the age of violence and scientific conditioning it depicts is already here, some people have been tempted to see it as a work of prophecy. But the work merely describes certain tendencies I observed in Anglo-American society in 1961 (and even earlier). True, there was not much drug-taking then, and my novel presents a milk-bar where you can freely ingest hallucinogens and stimulants, but I had only, just come back from living in the Far East, where I smoked opium regularly (and without apparent ill effects), and drug-taking was so much part of my scene that it automatically went into the book. Alex is very unmodern in rejecting “synthemesc”: his aim is to strengthen the will to violence, not enervate it. I think he is ahead of his time in preferring Beethoven to “teeny pop veshches,” but Kubrick’s film shows a way (especially in the record-store scene) to bridging the gap between rock music and “the glorious Ninth”—it is a clockwork way, the way of the Moog synthesizer.

* * *

Apart from being gratified that my book has been filmed by one of the best living English-speaking producer-directors, instead of by some pornhound or pighead or other camera-carrying cretin, I cannot say that my life has been changed in any way by Stanley Kubrick’s success. I seem to have less rather than more money, but I have always seemed to have less. I get odd letters from cranks, accusing me of sin against the Holy Ghost; invariably, I should think, masturbators, who, having seen the film, have discovered the book, used it as a domestic instrument of auto-erotic release, and then fastened their post-coital guilt onto me. Generally I am filled with a vague displeasure that the gap between a literary impact and a cinematic one should be so great, not only a temporal gap (book published 1962, film released ten years after) but an aesthetic one. Man’s greatest achievement is language, and the greatest linguistic achievement is to be found in the dramatic poems or other fictional work in which language is a live, creative, infinitely suggestive force. But such works are invariably ignored by all but a few. Spell a thing to the eye, that most crass and obvious of organs, and behold—a revelation.

I fear, like any writer in my position, that the film may supersede the novel. This is not fair since the film is only a brilliant transference of an essentially literary experience to the screen. Writers like Mailer and Gore Vidal—who have seen novels of theirs turned into abominable pieces of film craft—are not in this position. But I can console myself by saying that A Clockwork Orange is not my favourite book, and that the works of mine that I like best are so essentially literary that no film could be made out of them.

As Kubrick’s next film is to be about Napoleon, I find myself now writing a novel about Napoleon. God knows why I am doing this; there is no guarantee that he will use it, or even that the book will be published. Just the fascination of what’s difficult, or an expression of masochism that lies in all authors, or a certain pride in attacking the impossible. My Napoleon novel will be very brief, and to write a brief novel on Napoleon is far more difficult than to write War and Peace. But you can take this present labour as a product of the Orange film, and by God it is a labour.

Otherwise, my life is unchanged. What really enrages me is two minor dimensions—it is people referring to both film and book as THE Clockwork Orange. Can’t the bastards read? No, they can’t, and that’s what all the trouble is about.

* * *

All works of art are dangerous. My little son tried to fly after seeing Disney’s Peter Pan. I grabbed his legs just as he was about to take off from a fourth story window. A man in New York State sacrificed 67 infants to the God of Jacob; he just loved the Old Testament. A boy in Oklahoma stabbed his mother’s second husband after seeing Hamlet. A man in Kansas City copulated with his wife after reading Lady Chatterley’s Lover. After seeing A Clockwork Orange, a lot of boys will take up rape and pillage and even murder—The point is, I suppose, that human beings are good and innocent before they come into contact with works of art. Therefore all art should he banned. Hitler would never have dreamed of world conquest if he hadn’t read Nietzsche in the Reader’s Digest. The excesses of Robespierre stemmed from reading Rousseau. Even music is dangerous. The works of Delius have led more than one adolescent to suicide. Wagner’s Tristan and Isolde used to promote crafty masturbation in the opera house. And look what Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony does to Alex in A Clockwork Orange. If I were President of the United States, I should at once enact a total prohibition of films, plays, books and music. My book intended to be a delicious dream, not a nightmare of terror, beauty and concupiscence. Burn films—they make marvellous bonfires. Burn books. Burn this issue of ROLLING STONE.

Take the story as a kind of moral parable, and you won’t go far wrong. Alex is a very nasty, young man, and he deserves to he punished, but to rid him of the capacity of choosing between good and evil is the sin against the Holy Ghost, for which—so we’re told—there’s no forgiveness. And although he’s nasty, he’s also very human. In other words, he’s ourselves, but a bit more so. He has the three main human attributes—love of aggression, love of language, love of beauty. But he’s young and has not yet learned the true importance of the free will he so violently delights in. In a sense he’s in Eden, and only when he falls (as he does: from a window) does he become capable of being a full human being. In the American edition of the book—the one you have here—we leave Alex dreaming up new acts of violence. We ought to feel pleased about this, since he’s now exhibiting a renewal of the capacity for free choice which the State took away from him. The fact that he’s not yet chosen to be good is neither here not there. But in the final chapter of the British edition, Alex is already growing up. He has a new gang, but he’s tired of leading it; what he really wants is to have a son of his own—the libido is being tamed and turned social—and the first thing he now has to do is to find a mate, which means sexual love, not just the old in-out in-out. Here, for a bonus, is how that very British ending ends:

That’s what it’s going to be then, brothers, as I come to the like end of this tale. You have been everywhere with your little droog Alex, suffering with him, and you have viddied some of the most grahzny bratchnies old Bog ever made, all on to your old droog Alex. And all it was was that I was young. But now as I end this story, brothers, I am not young, not no longer, oh no. Alex like groweth up, oh yes.

But where I itty now, O my brothers, is all on my oddy knocky, where you cannot go. Tomorrow is like all sweet flowers and the turning vonny earth and the stars and the old Luna up there and your old droog Alex all on his oddy knocky seeking like a mate. And all that cal. A terrible grahzny vonny world really, O my brothers. And so farewell from your little droog. And to all others in this story profound shooms of lip-music brrrrrr. And they can kiss my sharries. But you, O my brothers, remember sometimes thy little Alex what was. Amen. And all that cal.

America prefers the other, more violent, ending. Who am I to say America is wrong? It’s all a matter of choice.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Further back and faster

• Penguin book covers

• Clockwork Orange bubblegum cards

• Alex in the Chelsea Drug Store

Very interesting article. Thanks for sharing.

Great article

I came here searching for Burgess’s accurate depiction of the three main human attributes. I’ve read all the article, of course, because of the second attribute.

Thanks.