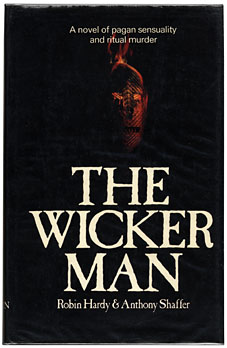

Left: The scarce first edition of the Hamlyn novelisation. From the Coulthart library.

Left: The scarce first edition of the Hamlyn novelisation. From the Coulthart library.

I realised some years ago that all my favourite films have great soundtracks, almost without exception. Something about the blend of drama and well-chosen music really excites me, so it’s no surprise that The Wicker Man would appeal, having as it does a wonderful folk soundtrack. Nice to see from the discussion that follows how influential this soundtrack has been although I’m surprised they didn’t mention the multiple cover versions of Willow’s Song. Once again Hollywood has seen fit to gift us with a completely redundant cover version of their own; the less said about the imminent remake, the better.

‘It was a way into a magical world’

The Wicker Man is the unlikely inspiration to a new generation of British folk musicians. So we put the film’s musical fans in a room with its director to discuss its enduring appeal. By Will Hodgkinson.

Will Hodgkinson

Friday July 21, 2006

The Guardian

ONE OF THE unlikeliest motivating factors in the current wave of new British folk music is a horror movie from three decades ago. The Wicker Man, the story of an upright Christian police officer investigating the disappearance of young girl on the Scottish island of Summerisle, and stumbling across a pagan cult, is hardly a masterpiece. But it has endured as a cult classic because it is unique, fascinating and evocative. Its folk-based soundtrack and use of ancient rituals and mythology have made it the focal point for a new generation of British musicians. So, as the gods of creation poured golden light into a sacred hall (a meeting room at the Guardian) on a summer afternoon, we assembled a handful of Wicker Man-obsessed musicians to discuss the film’s influence with its director, Robin Hardy… (more)

I’ll have to rent the movie on DVD as it’s been years since I’ve seen it and all I can really remember clearly is the shock ending which made it a movie you could never forget and an extremely bawdy song sung in a pub to the uptight puritanical Edward Woodward.

What’s the novel like?

There’s a decent DVD set that contains two versions of the film, one the short cut, the other, a longer version that’s unfortunately sourced from a video copy as the outtakes were lost. And the soundtrack CD is marvellous, of course.

The novel is pretty good, in fact “novelisation” is a rather insulting description since it’s more a proper novel based on the original screenplay. As a result, much of the pagan and folk background is fleshed out while minor aspects of the film are more fully developed. There’s also an odd coincidence: during the scene when Howie is watching the boys performing the maypole dance he thinks of the Lady Chatterley trial and the way that the prosecutor was disgusted by the mention of Lady Chatterley worshipping her lover’s balls. The book was written in 1978 so they couldn’t have know that the excellent Edward Woodward (who plays Howie in the film) would play that same prosecutor in a TV dramatisation of the trial in 1980 (not listed on his IMDB page for some reason).

He was also great in Breaker Morant

“Shoot straight you bastards. Don’t make a mess of it”

http://wwwmcc.murdoch.edu.au/ReadingRoom/film/dbase/2002/breaker.htm

I’ve got the “black” vinyl soundtrack LPon Trunk. Once described as “the most collectable record ever!” Who needs pensions when a piece of plastic will see me right in my dotage.