Sit through the credits for Monty Python’s The Meaning of Life and you’ll be rewarded at the very end with a written suggestion: “If you have enjoyed this film, why not go and see La Notte?” The joke being that a notoriously sombre offering from Michelangelo Antonioni is the antithesis of a laugh riot. In 1983 you could still poke fun at a director whose films were acclaimed as well as derided for being slow and serious; in 2022 this no longer seems likely. Antonioni hasn’t exactly been forgotten but his visibility as a cultural signifier has deflated considerably since his final feature in 1997, and the cinematic landscape has changed a great deal since 1983. The most significant change where Antonioni’s films are concerned is the way in which the techniques that once set him apart from many other directors have been thoroughly absorbed into the language of cinema. His predilection for sustained shots, for posing his characters in striking landscapes or architectural spaces, for refusing to offer simple explanations for the behaviour of those characters; none of this seems as radical as it did in the 1960s. We have a sub-genre today known as “slow cinema“, a form which Antonioni’s films helped make possible. It’s easy to characterise these aspects of the Antonioni oeuvre as running counter to a Hollywood that prefers everything to be swiftly delivered and comprehensible. But Antonioni’s techniques have followed the course of any aesthetic innovation which in time becomes a part of the available range of options for an artist, wherever that artist may be situated.

In 1963 Stanley Kubrick put La Notte on a list of 10 favourite films, and there’s a case to be made that 2001: A Space Odyssey is science fiction filtered through Antonioni’s sensibility; or there would be if Kubrick and Arthur C. Clarke were more concerned with human beings. A better candidate for SF Antonioni-style is Andrei Tarkovsky’s Solaris, and there’s a further case to be made that the continued popularity (or visibility) of Tarkovsky’s films is one of the main reasons we hear less today about the man Tarkovsky named in his diaries as “the best Italian director working today”. The first film Tarkovsky made after he left the Soviet Union was Nostalgia, a drama about a Russian writer in Italy that was co-written with Antonioni’s regular screenwriter, Tonino Guerra. (The pair began work on the Nostalgia screenplay while staying at Antonioni’s house.) Tarkovsky’s films are just as serious and slow as Antonioni’s, more so in most cases, but Tarkovsky remains visible because we’re living in a world where once-disreputable genres, science fiction in particular, are now a dominant form, and Tarkovsky just happened to make two cult science-fiction films. It’s difficult to imagine Antonioni being nakedly generic but Blow-up is partly a murder mystery, albeit one that refuses satisfactory explanation, while The Passenger is an extenuated thriller with all the dynamics pared away, and with the climactic event taking place while the camera is looking elsewhere. In Il Deserto Rosso Monica Vitti loses her mind in the industrial wastelands of Ravenna accompanied by the buzzes and whines of Vittorio Gelmetti’s electronic score. There’s nothing overtly science fictional about this but the film would make a fitting companion to a screening of Stalker.

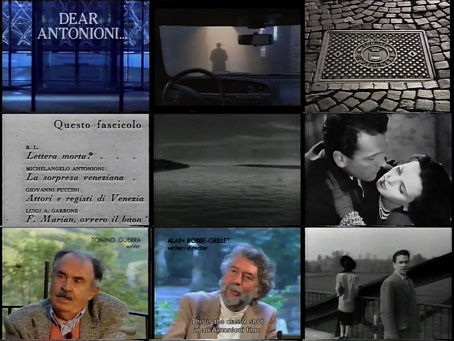

All of which brings us to Dear Antonioni…, a 90-minute documentary by Gianni Massironi which serves as an ideal introduction to the director and his works. The film was a co-production with the BBC, made to coincide with the release of Antonioni’s final feature, Beyond the Clouds, in 1997. Dear Antonioni… is also the title of an open letter to the director by Roland Barthes, passages from which are read by several of Antoninio’s actors. The readings punctuate a chronological examination of the director’s career, from his early documentaries and excursions into Neo-Realism to the features that established his reputation. If it had been made ten years earlier it might have hastened my appreciation of his films.

During my erratic self-education into the works of European directors I had a hard time getting used to Antonioni. I liked The Passenger very much, had a grudging respect for Blow-up, hated Zabriskie Point until the final 20 minutes or so, and for a long time regarded L’Avventura as over-rated. But my old video lists tell me that I taped this documentary anyway because I felt the problem was more a result of my own impatience rather than anything in the films themselves. A further problem was getting to see some of the films at all. I’ve mentioned before how difficult it used to be to appraise the work of directors outside the Anglosphere if you weren’t living in a city with a decent arts cinema. Il Deserto Rosso was never on TV, neither were La Notte or L’Eclisse, two major features which I still haven’t seen. The latter pair are mentioned in Dear Antonioni… but no clips are shown which makes me wonder if they were subject to a rights dispute like the one that kept several Hitchcock films out of circulation for many years. Antonioni himself is only present in historic interview footage but there’s plenty of production commentary from his screenwriters, Tonino Guerro, Sam Shepard, and Mark Peploe, plus more actors and collaborators including Monica Vitti, David Hemmings and Vanessa Redgrave. I’d also forgotten that Alain Robbe-Grillet turns up to present a lucid argument for Antonioni’s films as “Modern” (or Modernist) works in contrast to the Hollywood idiom exemplified by Alfred Hitchcock. I won’t attempt a précis of Robbe-Grillet’s remarks, it’s easier to suggest you hear them for yourself. Whether you’re a neophyte or an aficionado this is an unfailingly intelligent and absorbing study.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Michelangelo Antonioni, 1912–2007

I bought a boxed set from China which contains I think all of his feature films for a ridiculously low price and has obviously ripped off versions of some criterion collections of his more famous film. Have watched about half a dozen of them so far. Would have to agree on Zabriskie Point. If you watch his best 3 in chronological order

L’Avventura, La Notte and L’Eclisse

they do make a deep impression on you but as you write most of his novel ways of keeping us in suspense or boredom (depending on what sort of cinema you like) have now been adopted by mainstream cinema and don’t seem all that strange anymore.

Blow Up still holds up well as a time capsule of swinging London but after The Passenger none of the films are worth watching.

Slow cinema is well and good but sometimes watching Tarkovsky let a scene go on and one I keep wanting to press the fast forward button to get to the next bit.

Hey, Gabe. I’ve spent the past few years accumulating blu-ray filmographies of notable directors but Antonioni isn’t among them so I think I may fill in the gap this year. I like Blow-up more than I used to. It really clicked for me the first time I saw it in a full-frame TV screening when his divisions of the pictorial frame became much more evident.

I left out a mention in the piece above about Orson Welles’ dislike of Antonioni’s long takes but I like Welles’ films as much as Tarkovsky’s. The latter I’ve watched so many times they’re like old friends. You have to change your mental gears for “slow cinema”; if you can make the change then it can be very rewarding.

Dear John,

I only just came across your blog while in search for a printing solution. (who can print black edges?)

But that was over an hour ago; I’ve been devouring your content and absorbing some of this knowledge.

I find the paradigm you choose to use when you share content with the reader

refreshing and firm.

Thanks, Chris.

I’ve never seen Zabriskie Point. But I’ve read so much about it I’m not sure I want to spoil the version I carry around in my head by actually seeing the film.

John, an interesting point about the relationship between Tarkovsky and science-fiction. I first sought out Solaris precisely because it was billed as an “answer” to 2001. The film that made me a Tarkovsky fan was The Sacrifice. I saw it on American public television. I was mesmerized and very moved. When I hear critics talk about it being “lesser” Tarkovsky I can’t relate to that kind of calculation at all.

You’re not missing much with Zabriskie Point. I like the ending simply because it’s like a music video, with Pink Floyd playing an early version of Careful With That Axe, Eugene while various consumer products explode in slow motion. Antonioni was the wrong director to be making a film about the upheavals among American youth in the 1960s.

I do love L’Avventura, L’Eclisse, Red Desert and La Notte. Surely, the appreciation of so much culture is subject to ebb and flow. Right now Derek Jarman’s work is shining wonderfully in the critical spotlight, but a few years ago seemingly all you’d see mention of was his garden at Dungeness. Great works like The Last of England were seen as too extreme and rather de trop. Is Tarkovsky that much in fashion currently? Does this all depend on novelty? Whatever, thanks for the link, something to add to the list to watch.

Ebb and flow, of course. My comments about visibility are to do with the extent to which these kinds of directors are popular outside the worlds of critics and cineastes. Solaris and Stalker have an outsized popularity compared to Tarkovsky’s other films, and they continue to be influential. Kevin Martin and Ben Frost/Daníel Bjarnason have released alternate soundtracks for Solaris while a previous post here catalogued some of the Stalker-derived music. And that’s just the music world… When I was a regular Twitter user I used to see people posting/linking to Tarkovsky-related stories or images in a manner you didn’t see at all wth Antonioni. I doubt this would happen to the same degree without science fiction drawing attention to Tarkovsky’s work, even though he always dismissed the genre.

True. Though I wonder whether Tarkovsky’s tragic, premature death also plays a significant role. I think for critics Andrei Rublev is the greater film and I’d concur, much as I love Solaris and Stalker.

So, perhaps Tarkovsky is the William Burroughs of film directors!