I thought I’d finished with the arts documentaries until I remembered this four-part series from 1995. Hidden Hands was based on researches by Frances Stonor Saunders who also co-produced. As the subtitle suggests, the programmes examined aspects of Modernist art and architecture that weren’t exactly unknown but were often downplayed (sometimes deliberately ignored) by the art establishment. The episodes were as follows:

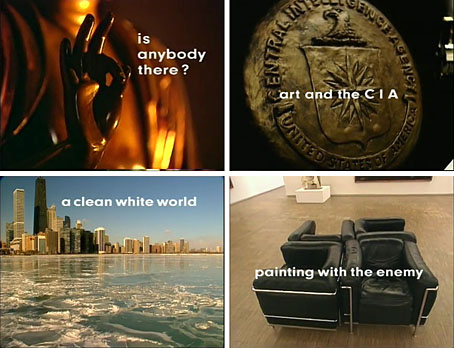

1: Is Anybody There? The occult roots of abstract painting, especially the influence of Theosophy on Vasily Kandinsky and Piet Mondrian. Kazimir Malevich and Frantisek Kupka are also mentioned at the beginning of the programme but we don’t hear anything more about them.

2: Art and the CIA. A history of the Congress for Cultural Freedom, a CIA front for channelling money to avant-garde exhibitions and literary magazines during the Cold War.

3: A Clean White World. Modernist architecture as a reaction to, and proposed solution for, the squalor of 19th-century city life. Also the similarity between the impulses that drove the Modernist architectural ideal, and the later health and purity obsessions of European fascist states.

4: Painting with the Enemy. The inadvertent way in which the animus towards “degenerate art” shared by the Nazis and the Vichy regime in occupied France helped sustain Modernism during the war years.

This is a very good series on the whole, informative and with a roster of authoritative interviewees. The narration overstates the contrarian angle in places but that’s television for you. Much of the history under investigation wasn’t necessarily hidden, more sidestepped by general discussions of 20th-century art. Even so, fifteen years earlier in the architecture episode of The Shock of the New, Robert Hughes covered similar territory and with similar criticisms, following the development of what would become known as the International Style while noting Mussolini’s adoption of a Modernist idiom for the architecture of Fascist Italy.

Elsewhere, when Hughes reviewed a major Kandinsky retrospective he paid sufficient attention to Kandinsky’s Theosophical beliefs; this was in 1982 for TIME magazine, not exactly an obscure publication. Theosophy’s ectoplasmic tentacles are all over the art of the late 19th century so you’d expect some crossover into the art of the new century, as there was in the careers of the artists themselves. (Matisse was a pupil of Gustave Moreau, for example, an inconvenient detail that often irritated critics.) Given the amount of artists swayed by Madame Blavatsky’s writings, a more interesting argument might have been to propose Theosophy as the prime cause of early abstraction rather than another inconvenient factor in its development. Hilma af Klint’s pioneering abstract paintings were as much products of her Theosophical studies as were those of Kandinsky but in the 1990s nobody was paying her very much attention.

Mondrian’s mysticism: Evolution (1910–1911).

As for the CIA, the agency’s clandestine cultural adventures were exposed by a leak in the late 1960s—Stephen Spender famously resigned in shame from his editorship of Encounter magazine—so this could almost be classed as old news. What you wouldn’t have had in the past, however, is the agents involved in the scheme openly discussing their activities.

These are minor quibbles. More objectionable—and I’d forgotten all about this—is the treatment of Henri Matisse in the final episode, in which the painter’s life in the south of France during the Second World War is contrasted with that of Picasso who deliberately spent the war years in Paris. Both artists had been condemned by the Nazis in the notorious “Entartete Kunst” (Degenerate Art) exhibition of 1937; both artists continued to paint during the occupation, but Matisse, who was never a political artist, gets criticised for working as before, while the creator of Guernica produced a succession of sombre (but unpolitical) canvases. Matisse was 70 years old when the Nazis invaded France so it would have been surprising if his painting turned suddenly to social commentary. The comparison makes little sense when the Surrealists are held up as somehow challenging the Vichy regime by playing “Exquisite Corpse” in their Marseilles hotel rooms. But the argument seems downright perverse when the previous episode in the series had Philip Johnson, of all people, as an interviewee. Johnson turned up in many documentaries about architecture in the 1980s and 90s—he’s in that same episode of The Shock of the New—so it’s no surprise to see him here. He’d been present at the birth of Modernist architecture, working with Le Corbusier and Mies van de Rohe, and became a major architect himself in later years. But controversy about his youthful fascist sympathies dogged his career. Johnson defends the collaborations of Le Corbusier and Walter Gropius by saying “architects like to work” but we hear nothing about his own activities.

The final episode is the weakest one, in other words, but the series as a whole is still worth watching, especially the CIA episode which is more fact than opinion. (Frances Stonor Saunders went on to explore this in depth in a book that I wouldn’t mind reading, The Cultural Cold War.) I’m amused that the CIA needed a front organisation for two reasons: first, and most obviously, they had to conceal the source of their funding from artists and organisers with left-wing views or even outright Soviet sympathies. But they also couldn’t afford to attract the attention of those US senators and congressmen who agreed with the two Josephs (Stalin and Goebbels) that all this modern painting and sculpture wasn’t art at all. Had the politicians known, the response would have resembled the NEA funding scandal thirty years later when America got its own very public discussion of what is or isn’t “degenerate” art. But that’s another story.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Televisual art

John, many thanks for this post. I was unaware of this series until now but shall watch it with great interest.

And before even af Klint, there was Georgiana Houghton and a bit later Emma Kunz. The School of Psychic Studies in Kensington have a few Houghton’s amongst their collection, which is well worth seeing. And there’s a good book on this, World Receivers: Georgiana Houghton – Hilma af Klint – Emma Kunz.

John, do make it a point to check out Cultural Cold War, as it is an excellently sourced and footnoted work, richly researched and, while never underplaying the significance of their findings, stays away from sensationalization, seeing as the truth in this case is sensational enough. And yes, the irony you mention above — i.e. keeping funding sources hidden so as not to upset the communist artists OR the Bircher senators and populist wags — is perhaps the most intriguing feature of said historical moment.

Steve: Yes, there’s been more sustained attention given to these artists and their beliefs in recent years, even whole exhibitions devoted to art and the occult. The attitude used to be (and you get a taste of this in the programme above) that anything that wasn’t a major religion was treated with disdain, even if (as with major religions) the belief system produced exceptional art.

Jerky: Thanks, it’s one for the reading list.

the series narration is false, or -to be polite- misleading. the “Entartete Kunst”exhibition in chapter 3 was the brain child of Carl Schneider the head of heidelberg psychiatry which followed the notorious 1922 prinzhorn book “Bildnerei der Geisteskranken” and was the stepping stone to the medically based systematic mass killing. the nazis, in chapter 2, did not followed modern architecture urge for clean & healthy living, certainly not the bauhaus.

if you are interested in storm of destruction caused by prinzhorn’s book i enclose here our article:

Authoritarian revisionism in Heidelberg psychiatry, the legacy of Hans Prinzhorn and Carl Schneider.

How a psychiatrist’s reaction to the Dada exhibitions in the First World War led to the Nazis’ medically based mass murders in the Second World War. The true story of the infamous “Prinzhorn” collection at Heidelberg University and the purpose it served.

Foreword

It is now one hundred years since Hans Prinzhorn published his book “Bildnerei der Geisteskranken” (“pictorial products of the mentally ill”) in 1922. High time, then, to take stock of the trail of destruction left by this concept of medicalising and therefore pathologising works of art. The hegemonic narrative is that insane “outsider art” was discovered by this German psychiatrist who collected the works in the Heidelberg University Hospital at which he worked and disclosed their existence by publishing this groundbreaking book that made these works and their influence known to the world.

When we came across a recent version of this cliché written by Guardian journalist Charlie English, we, the International Association Against Psychiatric Assault, decided that it was time to publish a different view of this event, based both on knowledge of the facts and it’s chronology and aimed at restoring human dignity to the victims. We feel that a counterstatement to the mystification of “art and madness” is needed, a look at the actual significance of Hans Prinzhorn for the Nazi concept of “degenerate art” as an ideological precursor of systematic medical mass murder (which in turn was an important waypost of the Shoah).

In 1916 during World War I, the first Dada exhibition took place in Switzerland. “The first great anti-art-movement, Dadaism or Dada, was a revolt against the culture and values that had caused the carnage of the First World War. The movement quickly evolved into an anarchist form of avant-garde art whose aim was to undermine the value system of the ruling organisation that had allowed the war to happen, including the art institution, which they saw as inseparable from the socio-political status quo.”1 Several of the exhibitors, Hans Arp, Hans Richter, Walter Serner and Ferdinand Hardekopf contributed works while they were incarcerated in the Kilchberg psychiatric sanatorium.2 Of course, it can be argued that they were “mentally ill”3, but it should also be remembered that several of them were not Swiss citizens and their stay in a mental institution offered them asylum from having to return to their countries and a certain forced conscription.

The background of the Dada exhibitions and perhaps other new art movements in the first years of the 20th century (Cubism, Futurism, Negro art, etc.4) is the reason for the reaction of authoritarian Heidelberg revisionism in the form of the Prinzhorn book, a reaction that defines the collection acquired in the psychiatric department of the University of Heidelberg. This is a diagnostic slander of the authors of the works in clinical-psychiatric terms. Prinzhorn wrote a letter in 1919 asking all institutions to send him works produced by their inmates. He thus took advantage of the common practice in psychiatric institutions throughout Germany, including Heidelberg, for psychiatrists to take possession of these works, who included them in the medical records as clinical evidence to support their psychiatric diagnoses. This was comparable to the looting by the colonial masters. Prinzhorn not only illegally collected these works (i.e. he did NOT bought/pay for the works) for a “museum of pathological art”6 or “his longed-for museum of pathological art”7, but also did NOT regard them as works of art. Charlie English writes about this, but it becomes even clearer in the clinical term Prinzhorn gives to the title of his book: “Bildnerei”. It means something like “pictorial products”.

The consequences:

A) The fact that the development of Dadaism had a profound impact on German art and poetry in the 1910s and 1920s allows only one conclusion: Dadaism was a real challenge to 20th century art and especially poetry, as it went against the traditional styles and values characteristic8 of traditional art and poetry in the social order, even if the Dadaists only experimented for about a decade. Nevertheless, Dadaist influences continued to be felt in the literary movements of the 20th century for a long time.

Against this tearing down of traditional boundaries, Heidelberg University Psychiatry, with Hans Prinzhorn’s collection “Bildnerei der Geisteskranken” (“pictorial products of the mentally ill”), by medically labelling artists as “mentally ill” on the basis of psychiatric diagnoses, reinforce the notion, that originated at the end of 19th century, of pathologisation of art. Art was thus no longer judged, or rather condemned, according to the work, but rather according to the supposedly “sick” mental state of the artists. We call this authoritarian revisionism. The Heidelberg University is at fault for reacting to the liberation of art through Dadaism with this authoritarian revisionism, thus revising this groundbreaking step for the modernising art of the 20th century. From the “cathedral of reason”, the university and it’s psychiatry, came the initiative to define art as a disease by assigning it to the madness of the insane. This initiative continues to this day, as artists are still discriminated against as “artists who are different”9 if they come from or have already been interned in asylums and/or psychiatric institutions. Wilmanns and Prinzhorn intended to use the works of art which they had acquired in psychiatric institutions in bad faith, i.e. looted art, to establish the Psychopathological Museum in Heidelberg, which indeed was opened on 13 September 2001.10

“…if the Führer had not put a stop to it”.11

B) This basic structure was further developed in the next step from 1933: “ill” became “degenerate” (“entartet”). In German, the word has a special meaning due to the formative part of the word: “art”, which is often not understood in other languages.

In German the word „art“ is in a biological context a basic unit of classification and a taxonomic rank of an organism. By using the word „entartet“, does not only define a human illness, but worse it excludes a person from being part of the human race. The moral taboo of murder had thus been broken for persons who are defamed in this way. It marked the ideological preparation of exterminist exclusion, first through forced sterilisation and marriage bans, then from 1939/40 through murder in gas chambers, which was exported to the gas murder factories in occupied Poland in 1942. From 1941, the centrally organised murders were transferred directly to the psychiatric prisons and continued through death by starvation until 1948/49.12

C) The logical consequence of this radical exclusion was then openly expressed by Carl Schneider, Karl Wilmann’s successor as chief physician of Heidelberg University Psychiatry. In his lecture published by the “Archiv für Psychiatrie und Nervenkrankheiten” (Archive for Psychiatry and Nervous Diseases) in 1939, he described the objective that modern art and the creators of this art should meet the same fate as he executed on the mentally ill shortly afterwards, i.e. their murder. As with the insane, he would select them beforehand: the painter Otto Dix name was specified! Then he would have them murdered in the same way, in order to then dissect their brains and to be able to present them as exhibits to his students in the lecture hall of the university psychiatry department, exactly where today the so-called “Prinzhorn Collection” is displayed, mocking its victims and demonstrating the hegemony and diagnostic power of psychiatry.

D) This basic ideological structure was not broken after 1949, only the killing stopped. It continued unchanged in “Art and Delusion” and is still the basis of exhibitions such as the 2005 “Biennale meine Welt” at the Museum “Junge Kunst” in Frankfurt-Oder.13

That Charlie English actively collaborated with the Prinzhorn Collection for his book “The Gallery of Miracles and Madness” can then no longer come as a surprise, especially since he titles the fourth part of his book “Euthanasia”. This very word was used in the language of the doctor-Nazis to cover up murder and we tirelessly demanded to stop using it in our publication on 17.2.2009. Our appeal: 14

Help make the perfect Nazi murders imperfect by….

1) …getting the Nazi jargon “euthanasia” (= physician-assisted suicide) banned from language use when it refers to the systematic medical mass murder from 1939 to 1949. The Nazis used the word “euthanasia” to cynically imply that it was the victims themselves who wished to die. Whenever you use this term, the victims are once again degraded, even in this present day. When you use this word for the systematic medical mass murder from 1939 to 1949, you help to reproduce the doctors’ Nazi ideology, expressing solidarity with the perpetrators and participate in the attempt to cover up their guilt…. ?

Conclusion:

We deplore the absence of a declaration of solidarity by the art world with the persecuted artists in psychiatry. Unfortunately, the art world has thus yet to take this step. In contrast, the Parisian students were exemplary when they demonstrated in solidarity against the expulsion of Daniel Cohn-Bendit by the De Gaulle government in 1968 with the slogan: We are all German Jews.

A similar reaction is missing, because Lucy Wasensteiner’s 2019 book The Twentieth Century German Art Exhibition: Answering Degenerate Art in 1930s London about the 1939 London exhibition also precisely misses this point. Here, too, reference is made only to the “proper” art of the time, while the art of the alleged “insane and mentally ill” continues to go unmentioned, a discrimination, despite being threatened with murder and manslaughter, or being persecuted, imprisoned and mistreated.

As a way to address this ongoing discrimination and finally disprove the myth of art and madness, we, IAAPA, propose an exhibition in a prominent location only of artworks by authors who remain anonymous, a wild mixture of authors who were suppressed in coercive psychiatry and by psychiatrists. For either modernism, like Dada, breaks with the boundaries of conventionality and normality in art, including anti-art, and abolishes these boundaries, or it clings to the idea that “mental illness” can show itself in ” pictorial products” („Geisteskrankheit“ in “Bildnerei”) – Prinzhorn’s choice of words – that excludes from art the works of those imprisoned and slandered in the psychiatric wards.

And of course, the collection of looted art in the lecture hall of the murderers in Heidelberg must finally be freed from the medical clutches of psychiatry and transferred to the museum “Haus des Eigensinns” until it can be handed over to its rightful owners, the heirs of the authors.15

Hagai Aviel, Tel Aviv, Israel, avielhagai@gmail.com

René Talbot, Berlin, Germany, r.talbot@berlin.de

——————————————————

1 https://www.daskreativeuniversum.de/dadaismus-dada-merkmale/

2 https://www.sanatorium-kilchberg.ch/site/assets/files/1259/20160620_mm_sanatorium _kilchberg_dada_ich_and_bermich_4603.pdf

3 By his own admission, Hans Richter was grateful for the rest of his life to be medically slandered with the psychiatric illness “juvenile imbecility”!

4 All the art movements mentioned several times in Carl Schneider’s lecture, for more details see footnote No. 11.

5 Expert opinion Prof Peter Raue: https://www.dissidentart.de/eigensinn/ungekuerztergutachten.htm

6 This is what Charlie English quotes in The Gallery of Miracles and Madness on page 25 from Hans Prinzhorn’s circular letter in June 1919

7 The Gallery of Miracles and Madness by Charlie English, page 43 and

8 See, for example, Kurt Schwitters “Sonata in Urlauten”: https://www.dissidentenfunk.de/archiv/s0504/audio/lo/t04.mp3

and Dadaism and German Poetry essay https://www.proessay.com/dadaism-and-german-poetry-essay/

9 See video of the opening of the exhibition “Bennale my world” on 13.3.2005: https://youtu.be/0lMauyX51z4?t=1636

10 https://web.archive.org/web/20170509215044/http://www.autonomes-zentrum.org/ai/prinzhornprotest.html

11 Quote from “Entartete Kunst und Irrenkunst” (Degenerate Art and Mad Art), the speech by Carl Schneider, head of the Heidelberg University Psychiatric Clinic, who succeeded Wilmanns as head of the Psychiatric Clinic in Heidelberg and whose collection was headed by Hans Prinzhorn, held on 19 March 1939, published in Archiv für Psychiatrie Und Nervenkrankheiten, page 164, 1939 – Springer https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/BF01814830

In the speech he refers, among other things, to the paintings by Otto Dix, but also to texts by Schwitters. Degenerate artists and mentally ill artists have in common, he says, that they are exempt from work and that their work is promoted by communists and Jews, and this endangers the Nordic true artists. Then he reports on his notorious findings from work therapy (for which he is also so revered by Klaus Dörner in Klassische Texte neu gelesen, in Psychiatrische Praxis 13 (1986), pp. 112-114: Carl Schneider, “the theorist who, in terms of scientific theory, could hardly be surpassed in the 20th century…”). One can get the schizophrenic artist to produce normal work through appropriate medical care – by destroying his works and leading him to a normal profession. The full text of the speech is documented here: http://www.iaapa .de/…

12 Heinz Faulstich, Starvation in Psychiatry 1914-1949

13 See video of the opening of the exhibition: https://youtu.be/0lMauyX51z4?t=1636

14 English: https://www.iaapa.de/8_demands.htm German: https://www.iaapa.de/8_demands.htm#dt

15 See the 7th demand: http://www.iaapa.de/8_demands.htm

Thanks, I noted my reservations about the series in the post. I’d always suggest that curious viewers take a TV programme as a rough introduction to a subject. Television has never been as useful a medium for sustained investigation the way books have been and still are.

Beyond that, if your comment is part of some campaign then I’d suggest trying to be a little more succinct. It should be possible to make your point without flooding a comments box with so much text.