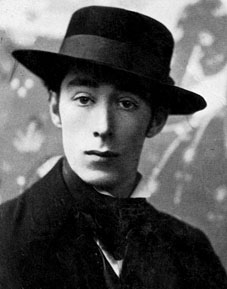

This week’s book purchase (yes, dear reader, it never ends, there are merely lulls between one indulgence of the vice and the next) is a small Bodley Head volume that comprises part of the collected works of Hector Hugh Munro (1870–1916), or “Saki” as he’s better known. I have Saki’s complete works already in a big fat Penguin collection but I like these small books that were the common format for portable reading prior to the invention of the paperback. Over a number of years I’ve managed to collect about half of the Tusitala Edition of Robert Louis Stevenson’s complete works which are similarly-sized blue volumes (one in a rare leather binding), simply through chance finds in secondhand shops.

This particular book is a 1929 reprint of The Chronicles of Clovis collection first published in 1911 and, like the Stevenson volumes, has the author’s signature blocked in gold on the cover. The introduction is by AA Milne and I’m taking the liberty of reproducing it in full below, partly out of laziness and partly because he does a good job of presenting the man and his work.

THERE are good things which we want to share with the world, and good things which we want to keep to ourselves. The secret of our favourite restaurant, to take a case, is guarded jealously from all but a few intimates; the secret, to take a contrary case, of our infallible remedy for seasickness is thrust upon every traveller we meet, even if he be no more than a casual acquaintance about to cross the Serpentine. So with our books. There are dearly loved books of which we babble to a neighbour at dinner, insisting that she shall share our delight in them; and there are books, equally dear to us, of which we say nothing, fearing lest the praise of others should cheapen the glory of our discovery. The books of “Saki” were, for me at least, in the second class.

It was in the Westminster Gazette that I discovered him (I like to remember now) almost as soon as he was discoverable. Let us spare a moment, and a tear, for those golden days in the early nineteen hundreds, when there were five leisurely papers of an evening in which the free-lance might graduate, and he could speak of his Alma Mater, whether the Globe or the Pall Mall, with as much pride as, he never doubted, the Globe or the Pall Mall would speak one day of him. Myself but lately down from St. James‘, I was not too proud to take some slight but pitying interest in men of other colleges. The unusual name of a freshman up at Westminster attracted my attention; I read what he had to say; and it was only by reciting rapidly with closed eyes the names of our own famous alumni, beginning confidently with Barrie and ending, now very doubtfully, with myself, that I was able to preserve my equanimity. Later one heard that this undergraduate from overseas had gone up at an age more advanced than customary; and just as Cambridge men have been known to complain of the maturity of Oxford Rhodes scholars, so one felt that this Westminster free-lance in the thirties was no fit competitor for the youth of other colleges. Indeed, it could not compete.

Well, I discovered him, but only to the few, the favoured, did I speak of him. It may have been my uncertainty (which still persists) whether he called himself Sayki, Sahki or Sakki which made me thus ungenerous of his name, or it may have been the feeling that the others were not worthy of him; but how refreshing it was when some intellectually blown-up stranger said “Do you ever read Saki?” to reply, with the same pronunciation and even greater condescension: “Saki! He has been my favourite author for years!”

A strange exotic creature, this Saki, to us many others who were trying to do it too. For we were so domestic, he so terrifyingly cosmopolitan. While we were being funny, as planned, with collar-studs and hot-water bottles, he was being much funnier with werwolves (sic) and tigers. Our little dialogues were between John and Mary; his, and how much better, between Bertie van Tahn and the Baroness. Even the most casual intruder into one of his sketches, as it might be our Tomkins, had to be called Belturbet or de Ropp, and for his hero, weary man-of-the-world at seventeen, nothing less thrilling than Clovis Sangrail would do. In our envy we may have wondered sometimes if it were not much easier to be funny with tigers than with collar-studs; if Saki’s careless cruelty, that strange boyish insensitiveness of his, did not give him an unfair start in the pursuit of laughter. It may have been so; but, fortunately, our efforts to be funny in the Saki manner have not survived to prove it.

What is Saki’s manner, what his magic talisman? Like every artist worth consideration, he had no recipe. If his exotic choice of subject was often his strength, it was often his weakness ; if his insensitiveness carried him through, at times, to victory, it brought him, at times, to defeat. I do not think that he has that “mastery of the conte”?in this book at least—which some have claimed for him. Such mastery infers a passion for tidiness which was not in the boyish Saki’s equipment. He leaves loose ends everywhere. Nor in his dialogue, delightful as it often is, funny as it nearly always is, is he the supreme master; too much does it become monologue judiciously fed, one character giving and the other taking. But in comment, in reference, in description, in every development of his story, he has a choice of words, a “way of putting things” which is as inevitably his own vintage as, once tasted, it becomes the private vintage of the connoisseur.

Let as take a sample or two of “Saki, 1911.”

The earlier stages of the dinner had worn off. The wine lists had been consulted, by some with the blank embarrassment of a schoolboy suddenly called upon to locate a Minor Prophet in the tangled hinterland of the Old Testament, by others with the severe scrutiny which suggests that they have visited most of the higher-priced wines in their own homes and probed their family weaknesses.

“Locate” is the pleasant word here. Still more satisfying, in the story of the man who was tattooed “from collar-bone to waist-line with a glowing representation of the Fall of Icarus,” is the word “privilege”:

The design when finally developed was a slight disappointment to Monsieur Deplis, who had suspected Icarus of being a fortress taken by Wallenstein in the Thirty Years’ War, but he was more than satisfied with the execution of the work, which was acclaimed by all who had the privilege of seeing it as Pincini’s masterpiece.

This story, The Background, and Mrs. Packletide’s Tiger seem to me to be the masterpieces of this book. In both of them Clovis exercises, needlessly, his titular right of entry, but he can be removed without damage, leaving Saki at his best and most characteristic, save that he shows here, in addition to his own shining qualities, a compactness and a finish which he did not always achieve. With these I introduce you to him, confident that ten minutes of his conversation, more surely than any words of mine, will have given him the freedom of your house.

AA Milne

I often wonder how many people read Saki today. I’ve been reading his stories far longer than those of many other writers for the simple reason that a handful of his works are vaguely supernatural and so were encountered at an early age in ghost story collections. Their humour and the author’s unusual name made his work immediately memorable. Saki’s world is essentially the same as that of the still hugely popular PG Wodehouse but, as Milne notes, there’s a cruelty at the heart of Saki one doesn’t find in Wodehouse or other comic authors of the period. Wodehouse’s heroes are usually cheerful buffoons; Saki’s are smart, viciously witty, endlessly self-regarding and sophisticated, and always out for themselves. If they can cause chaos among those they despise or find boring, so much the better. The Saki hero lives the same life of idleness as Wooster and company, resentfully dependent on the indulgence of monstrous aunts and other unwanted family members as he flits from London to rambling country mansion and back again. He is vain, deeply snobbish, often misogynist and always very funny.

I often wonder how many people read Saki today. I’ve been reading his stories far longer than those of many other writers for the simple reason that a handful of his works are vaguely supernatural and so were encountered at an early age in ghost story collections. Their humour and the author’s unusual name made his work immediately memorable. Saki’s world is essentially the same as that of the still hugely popular PG Wodehouse but, as Milne notes, there’s a cruelty at the heart of Saki one doesn’t find in Wodehouse or other comic authors of the period. Wodehouse’s heroes are usually cheerful buffoons; Saki’s are smart, viciously witty, endlessly self-regarding and sophisticated, and always out for themselves. If they can cause chaos among those they despise or find boring, so much the better. The Saki hero lives the same life of idleness as Wooster and company, resentfully dependent on the indulgence of monstrous aunts and other unwanted family members as he flits from London to rambling country mansion and back again. He is vain, deeply snobbish, often misogynist and always very funny.

Clovis Sangrail was merely a new incarnation of Saki’s earlier Reginald, both characters being masks which the author used to describe a smarter, wittier, more handsome version of himself. The Chronicles of Clovis is deceptively titled since Clovis himself is often only a background presence in the stories and, in the oft-reprinted Sredni Vashtar, is entirely absent. In that story a sickly ten-year-old boy plots a devastating vengeance against his hated guardian when she decides to have his pets destroyed. Saki’s life paralleled that of his characters; his mother died from a miscarriage after being charged by a cow (!) so he and his sister were raised by relatives that he grew to despise. Many of these stories can be seen as his bitter revenge.

It’s amusing to read that Saki “may have been homosexual” when so much of his work could hardly have been written by someone who wasn’t. The introduction in the collected Penguin edition is by Noël Coward, and a direct line may be drawn from Oscar Wilde’s characters, through Saki, to Coward’s drawing rooms. Wilde is more generous and philosophical, Coward is more serious (when he wants to be), but all three share a gay writer’s delight in arch wit and sarcastic dismissal. Many of Reginald’s quips could have been borrowed from Wilde’s Lord Henry Wotton: “I always say beauty is only sin deep”, “To have reached thirty is to have failed in life.” And Reginald, like Lord Henry, enjoys being scandalous.

“Never,” wrote Reginald to his most darling friend, “be a pioneer. It’s the Early Christian that gets the fattest lion.”

Thus the opening of Reginald’s Choir Treat, wherein Reginald enlivens his stay in a village by persuading the local choirboys to indulge in a river bathe before marching them naked through the streets in a Bacchanalian procession, playing improvised flutes and singing a Temperance song as they go. Clovis also looks forward to introducing some impressionable youths to poker but that’s as far as we get with active corruption, and little wonder a mere decade after Oscar Wilde’s ignominious trial. Gabriel-Earnest is the werewolf story to which Milne refers but in Saki’s world a wild supernatural creature manifests during the day as a naked teenage boy. In the story Saki’s sympathies are firmly on the side of the werewolf, not with the stuffy adults whose lives he disrupts (or, it should be said, with the working-class children that he eats). In The Chronicles of Clovis we also have The Music on the Hill, a more serious story that could be described as Machen-light, which sees a youthful and dangerous Pan incarnated in the English countryside. There’s a curious thread of paganism running through Saki’s work which seems deeply-felt, possibly because he preferred animals to most people. The boy in Sredni Vashtar offers up a prayer to his pet ferret, while in The Story of Saint Vespaluus Clovis relates the tale of a pagan king’s young nephew who seems to have converted to Christianity but who, after the king has died, admits it was all a joke, and he’s really a serpent-worshipper after all. Clovis describes the boy-saint with some relish, twice telling us how good-looking he was:

…he was quite the best-looking boy at Court; he had an elegant, well-knit figure, a healthy complexion, eyes the colour of very ripe mulberries, and dark hair, smooth and very well cared for.”

“It sounds like a description of what you imagine yourself to have been like at the age of sixteen,” said the Baroness.

“My mother has probably been showing you some of my early photographs,” said Clovis. Having turned the sarcasm into a compliment, he resumed his story.

Saki, like William Hope Hodgson, was too old to enlist when the First World War broke out but he did so anyway and, like Hodgson also, died in a nameless field somewhere in France. Coward speculates how he would have fared had he survived into the Twenties, and he acknowledges Wilde’s precedent along the way:

His articulate duchesses sipping China tea on their impeccable lawns, his witty, effete young heroes Reginald, Clovis Sangrail, Comus Bassington, with their gaily irreverent persiflage and their preoccupation with oysters, caviar and personal adornment, finally disappeared in the gunsmoke of 1914. True, a few prototypes have appeared since but their elegance is more shrill and their quality less subtle. Present-day ideologies are impatient, perhaps rightly, with aestheticism. World democracy provides thin soil for the growing of green carnations, but the green carnations, long since withered, exuded in their brief day a special fragrance, which although it may have made the majority sneeze brought much pleasure to a civilised minority. In this latter group I am convinced that there will always be enough admirers of Saki to keep his memory fresh. I cannot feel that he would have wished for more.

Fortunately for us today his works are easily found online. Project Gutenberg has a number of texts in different formats and this site by a Clovis enthusiast has all the Clovis stories gathered in one place. If you only read one story, go away now and read the two-and-a-half pages of The Open Window. There’s no Clovis or Reginald to be found there but it’s a masterpiece of concision, surprise and wit.

Previously on { feuilleton }

• Alla Nazimova’s Salomé

• Joe Orton

• The Picture of Dorian Gray I & II

I quite like Saki’s stories but it is true that I had never hear of him during my studies in France. Like for many foreign authors, I discovered his works by going on a random book binge…

Makes me wonder also how much he’s read outside Britain. Not all writers get translated, after all.

Actually I read it in English (a second hand penguin – those where the days wehre I had to choose between reading and eating).

He is translated and available on the French market (a quick look on the FNAC server shows a number of books there) but I would venture that he is not very well known at all.

Same goes for Italian.

Oh, that’s good to know. I guess he’s not too snobbish or effete for other nations, then. Great seeing the titles in French: L’insupportable Bassington, Le cheval impossible, La fenêtre ouverte.